There is no doubt that Timor-Leste has made significant progress since independence. While its current Human Development Index ranking is 134 out of 187 countries, its HDI score has increased more than that of East Asia and the Pacific as a whole, which is saying something. However, Timor-Leste still faces serious risks and challenges. Australia has a special relationship with Asia’s youngest nation, as reflected in the announcement by Australia’s parliament of an inquiry into Australia’s relationship with Timor-Leste by the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. The Development Policy Centre has made a submission to the inquiry, summarised here, and available in full here [pdf], which at some point will be posted on the Committee’s website.

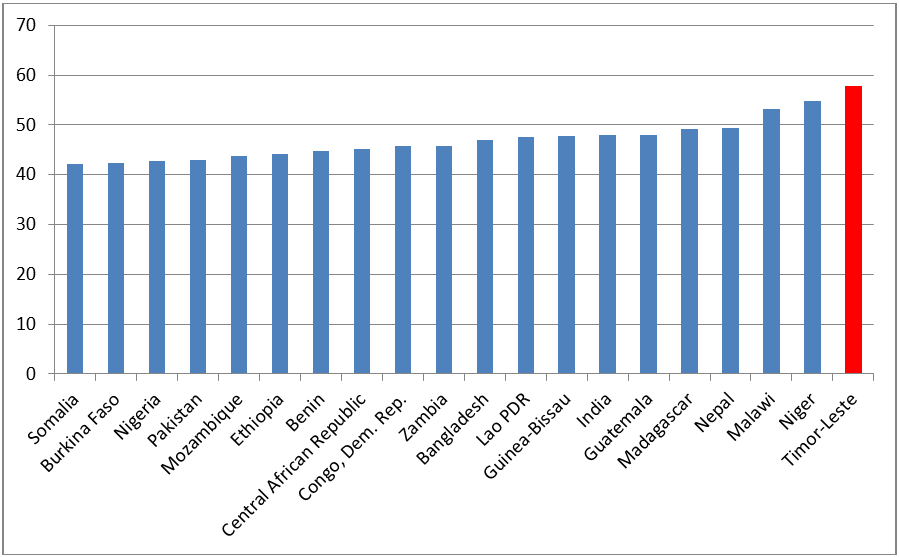

A remarkable fact about Timor-Leste is that, according to World Bank statistics, and as illustrated in the graph below, it has the highest incidence of under-five malnutrition, as measured by height-for-age, in the world.

Percentage of under-five population malnourished, as measured by height for age (stunting), for the 20 worst countries

Source: World Bank DataBank. Year is the most recent for which data is available, from 2006 onwards.

Source: World Bank DataBank. Year is the most recent for which data is available, from 2006 onwards.

In recognition of this, many point to agriculture as the sector which needs most urgent attention in Timor-Leste. But the country has masses of oil and gas. It is not as if it can’t buy food, and agriculture, while certainly important, is never going to be a massive generator of employment. More employment would spread purchasing power throughout the population, thereby helping to address food insecurity and malnutrition, as well as promoting political and social stability.

Youth unemployment rates in Timor-Leste are very high, and unemployment rates more generally are also high, especially in urban areas. Timor-Leste has the ninth-youngest population in the world, and a high population growth rate, which if continued will see the population double in 30 years.

Of course, domestic employment generation will be important, but in our submission we emphasise the importance of taking a regional approach to Timor-Leste’s employment problems. In particular, we advocate that Australia adopt a regional employment strategy to give Timorese access to employment and training opportunities in Australia. Young Timorese given the chance of work in Australia would have a strong incentive to acquire basic and advanced skills, including English-language competence. Though only a small number of Timorese would benefit directly, relative to the size of the youth cohort, the overall effect would be much greater owing to the spillover effect it would have by increasing demand for skills training in Timor-Leste. Remittances sent home by Timorese in Australia are of course another benefit that could, among other things, help others in their families to pay for skills and language training in Timor-Leste.

Timor-Leste has already moved to give a small number of its citizens access to overseas employment options. About 1,100 Timorese are in South Korea under a bilateral employment agreement to work in factories and fishing companies between 2009 and 2012. Australia now includes Timor-Leste in its Seasonal Worker Program. The scheme, however, remains tiny and, despite the strong people-to-people links between the two countries, Australia has so far done little else to promote overseas employment opportunities for the people of Timor-Leste.

How Australia can improve on that record in the future takes up the bulk of our submission. We spell-out eight steps:

1. Australia, through the aid program, should establish and subsidise, preferably with cost-sharing from the Timor-Leste government, an English language centre focused on preparing Timorese for international skills training, tertiary education and employment.

2. Australia should provide, and in some way subsidise, Timorese access to the Australia-Pacific Technical College or to Australian technical colleges to obtain technical qualifications recognised in Australia.

3. Australia should provide access to work placements in Australia and the Pacific that lead to significant workplace experience.

4. Australia, through the aid program, and preferably with cost-sharing from the Timor-Leste Government, should fund recruitment services to help Timorese with appropriate Australian-recognised skills to access the Australian job market under existing visa categories.

5. The Government should reform the Seasonal Worker Program and related arrangements. We identify five ways to get started: (i) make payment of the air fare to Australia an employee responsibility; (ii) crack down on illegal labour; (iii) promote the scheme through employer groups; (iv) remove the current incentives for backpackers to work in horticulture; and (v) remove the geographical restrictions on seasonal tourism.

6. Provide Timor-Leste with access to the Work and Holiday visa and don’t restrict access to tertiary graduates. The quota could start low and increases could be made conditional on a low (close to zero) overstay rate.

7. Introduce a Regional Access Quota, as New Zealand has, to provide a limited number of permanent residency slots to citizens of Australia’s vulnerable neighbours, including Timor-Leste.

8. Launch discussions with New Zealand on the prospect of expanding the Closer Economic Relationship between Australia and New Zealand to include, on a progressive and conditional basis, third countries such as Timor-Leste and other Pacific island countries.

What about aid?

Our submission also covers the aid program, though you’ll have to read it to see what we have to say. Of course aid is important. Australia is Timor-Leste’s primary aid donor, and has been since its independence, providing almost $1 billion since 1999. Timor-Leste has also been among the top ten recipients of Australian aid throughout that period, making the aid relationship an important one for both parties. But whatever aid can do, it is not good at creating jobs. As outlined above, aid could be part of the regional employment strategy which Timor-Leste desperately needs, but Australia will have to go beyond aid, to an aid-plus-labour-mobility strategy, if it really wants to make a difference in Timor-Leste.

Richard Curtain is a Melbourne-based public policy consultant and worked on this submission during his time as a Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. Robin Davies is Associate Director of the Centre. Stephen Howes is Director of the Centre.

Whilst I agree entirely that Australia ought facilitate better access to employment opportunities in Australia, the opportunities will only ever directly benefit a very small percentage of the population. Currently over three quarters of the population are directly dependent upon agriculture for their livelihood. Strategies that focus on improving agricultural production, diversifying and value adding (eg through making tofu/tempeh from locally grown soybean) timber production with rural based timber and bamboo milling and local furniture making, more intensive cattle production, mini dams to capture wet season water to use for year round vegetable crop production are a few examples of the ways in which the long term employment and prosperity of Timorese can be grown in country.

I also think it is fanciful to imagine that the Australian horticultural Industry that lobbied for years to get better access to the labour market would be at all grateful if the incentives for backpackers to work in agriculture were to be removed.

I agree entirely with the other reforms to the seasonal worker scheme suggested. It’s a powerful disincentive for potential employers if they have to front for an airfare for sight unseen workers , especially given that Timorese workers generally have poor english language skills and close to zero experience in modern commercial horticulture. The existing demands for pastoral care put a further impost on potential employers.