On 17 December the World Bank announced that it had concluded negotiations for a $US 52 billion replenishment of the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, the International Development Association (IDA). The new funding will back concessional loan and grant commitments to be made over the next three years. This seventeenth IDA replenishment (IDA17) is about $US 3 billion bigger than the previous one (IDA16, concluded in late 2010) which leaves funding broadly flat in real terms.

So how generous was Australia this time around? Surprisingly, in the new world of aid transparency, the World Bank will not be releasing details of the replenishment until March. (One has to wonder how they can announce the total size of the replenishment if they are not in a position to detail its components.) The Australian Government hasn’t made an announcement either. So we asked DFAT, and were informed (via the statement at the end of this post) that Australia’s contribution is expected to amount to $735 million or so. That is $95 million less than the amount Australia gave IDA for the last three years, which was $830.5 million.

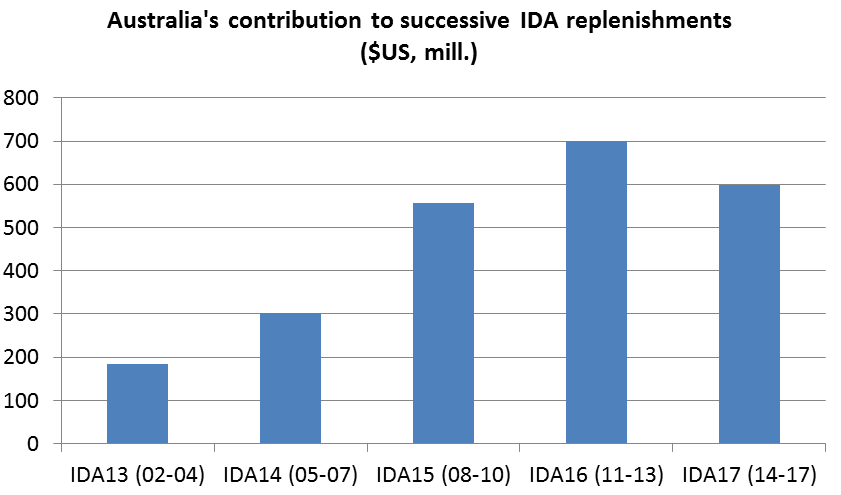

The reduction brings to an end a series of extraordinary increases in Australian support for IDA, first under Howard and then under Rudd and Gillard, as the graph below illustrates (see the notes below for sources and assumptions).

How did the cut come about? A forbiddingly complex set of calculations are involved in IDA replenishments, but the bottom line is that last time (in IDA16) we made a $100 million “supplemental” or one-off contribution, on top of our normal contribution to IDA, which we are not making this time.

How did the cut come about? A forbiddingly complex set of calculations are involved in IDA replenishments, but the bottom line is that last time (in IDA16) we made a $100 million “supplemental” or one-off contribution, on top of our normal contribution to IDA, which we are not making this time.

The Government will defend the decision by saying that our “burden share” in IDA17 is unchanged at 1.8% (as DFAT informed us through their statement). It is true that Australia’s IDA burden share was increased under Rudd from 1.46% to 1.8% (in December 2007 as part of IDA15), and that the Government could have made things worse for IDA if it had reverted to a lower share. At the same time, IDA burden shares are rather limited as measures of donor effort: several donors make additional contributions, such as Australia’s $100 million last time. And, oddly, there is no requirement that these shares add to 100%. (In IDA16, they summed to about 75%! We don’t know what they add to for IDA17.)

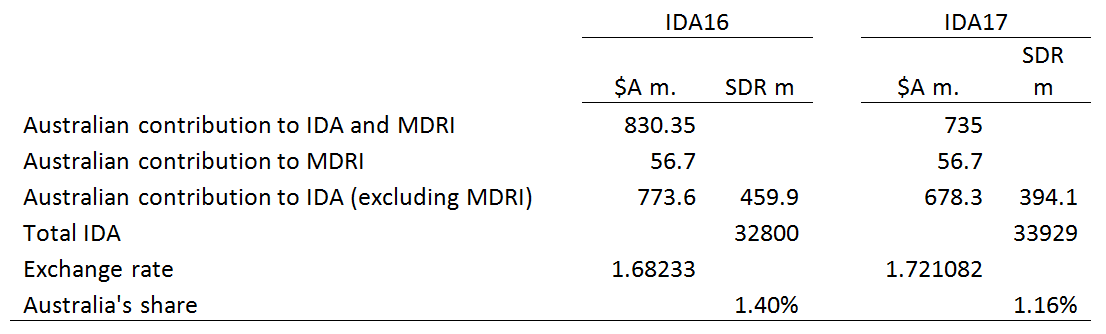

A simpler and more holistic way to judge Australia’s contribution is to look at our overall IDA share: how much we give divided by the total raised. In the last replenishment, our share was 1.40%. This time round, our estimate of Australia’s share is 1.26%. These estimates are subject to certain caveats (for which see the notes), but it is roughly a 10% reduction in overall share.

So why the cut? Australia wasn’t the only country that reduced funding relative to IDA16. Full details aren’t available but sometraditional donors seem to have given less, while other traditional and some emerging donors have provided more.

The Coalition signalled before the election that it was going to be less multilateral than Labor. Given this, and the end of the scale-up in aid, the outcome is not that surprising. But note that, also late last year, the Global Fund, though denied an increase by Australia, escaped a cut in its latest replenishment round.

It is not clear why the World Bank was singled out for a cut, especially given its focus on economic development, a key priority for the Coalition. Probably the reason is simply that the “supplemental” contribution of three years ago was an easy target. But that is hardly a satisfactory rationale.

The World Bank, of which IDA is an integral part, was recently rated by the 2012 Australian Multilateral Assessment as one of 13 out of 42 multilateral organisations in relation to which Australia could have confidence “that increases in core funding will deliver tangible development benefits in line with Australia’s development objectives, and that the investment will represent good value for money.” The Global Fund was not in this exclusive list.

On the one hand, the cut to IDA is relatively small, at least when placed in historical context. On the other, the Multilateral Assessment doesn’t seem to be serving the purpose for which it was introduced; namely to provide an objective basis for multilateral funding decisions.

Notes and calculations

- The share calculations exclude funding of the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), since this is also excluded from the IDA total, and assume that our MDRI commitments this time are the same as the previous replenishment ($57 million). Information about Australia’s MDRI contribution this replenishment is not yet available.

- Exchange rates from the World Bank. SDRs are the “currency” in which IDA replenishments are officially measured.

- The source for the graph is p.29 of this World Bank document. The IDA17 figures are calculated by us, making the same assumption for MDRI, and using the same exchange rates as per the table above. Given the appreciation of the Australian dollar in recent years, the fall between rounds in $US (or SDR) is not as great as in $A.

The DFAT statement in full reads:

“On 17 December 2013, Australia pledged to maintain its burden share to the seventeenth replenishment of the World Bank’s concessional lending arm, the International Development Association (IDA17).

Consistent with our earlier contribution to IDA16, our burden share will be 1.80 per cent for contributions to IDA loans and grants, and 1.61 per cent for IDA’s debt relief initiatives. Australia will also meet its expected obligations for the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative.

How this pledge equates in dollar terms remains subject to confirmation by the World Bank, but is expected to be in the order of $735 million.”

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre. Jonathan Pryke is a Researcher at the Centre.

I agree the IDA17 and Global Fund pledges don’t seem to rest on any objective basis, whether it’s the findings of the Australian Multilateral Assessment (possibly skewed in the case of the Global Fund by a passing storm about the misappropriation of funds in Africa), or something else.

However, I don’t see any real cutting going on, or any singling out of the World Bank, and am surprised by this in light of the Treasurer’s pre-election comments about funding to multilateral organisations.

While friends of the Global Fund might have hoped for a large increase in Australia’s contribution to the fourth replenishment, a same-nominal contribution of $200 million over three years was not to be sneezed at in the context of a flatlined Australian aid budget.

As for IDA17, a government truly intent on reaping savings from the multilateral part of the aid budget could well have chosen to revert to the pre-2007 burden share of 1.46 per cent. This would have yielded further savings of perhaps $130 million. Instead, the government maintained the higher burden share adopted by Labor for IDA15 and IDA16.

Failing to repeat Labor’s IDA16 supplementary contribution of $100 million didn’t in any real sense constitute a cut, given that the whole point of describing a contribution as ‘supplementary’ is to convey that it will not necessarily be repeated. In fact I doubt Labor would have repeated it if re-elected, given their own large cuts, in 2012 and 2013, to the forward estimates for the aid budget, as well as reallocations within the aid budget for asylum-seeker costs. World Bank management should be well pleased that Australia maintained its 1.8 per cent share.

By the way, I’m not sure we can yet evaluate the significance of the fall in Australia’s share of the total replenishment, from 1.4 to 1.26 per cent, as we don’t know whether certain other donors’ contributions, provided for the first time as ‘concessional partner loans’, have been included in the headline total on a gross or net basis (see this piece from CGD’s Todd Moss).

I think that what we are really seeing here is decision-making on a default basis, not particularly constrained at this stage by the new aid budget environment and certainly not informed by any strategic framework for the allocation of resources to multilateral organisations—or to anything much. That’s good for the organisations or causes that pass through the door early. It’s not so good for those whose turn comes around when the cupboard is empty.