In global health circles, Dr Eric Goosby’s reputation precedes him. A physician by training, he has been a leader in the development and implementation of HIV/AIDS policy for 30 years and is perhaps best known for his role as the US Global AIDS Coordinator (2009-2013). In 2015, Dr Goosby accepted an appointment as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Tuberculosis (TB), and it was in this capacity that he recently visited Canberra, during which I had the opportunity to interview him for the Devpolicy podcast.

We began the conversation by talking about his current role, and how working on TB connects with his previous work on HIV. Explaining that Special Envoys are a means for the UN Secretary-General to bring attention to issues that cut across UN agencies, Dr Goosby noted,

I was appointed under Ban Ki-moon, and his hope was that the countries that I already had established a relationship with through my work with HIV would be the same countries that needed strengthening and help in their TB response. Plus, there’s a co-infection relationship with HIV. Many of the increases in TB globally are in one way or another connected to the HIV population, especially in developed settings.

Another key theme that links the TB and HIV/AIDS responses is the way in which they highlight disparities in human rights and equity. While 90 per cent of TB cases can theoretically be prevented, diagnosed, treated, and cured, health systems worldwide have failed to prioritise the identification and retention of TB patients on treatment:

It’s not the kind of disease that you can just kind of pop in and out of a primary care system without real preparation. Easily prepared for, but you need to prepare for it. …[Identifying] strategies to keep people on care for six months, which is all it requires – as compared to HIV, which is the rest of your life – is a challenge to every single medical delivery system I’ve looked at. So, it’s harder than it seems.

A related issue that we came to later in the interview was how health systems can manage the shifting global disease burden caused by the rise in noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, and co-infection of these with TB. Dr Goosby acknowledged that while NCDs are becoming more dominant, and that “an integrated primary care health package is where the planet needs to go”, infectious diseases including TB will continue to trouble us for some time yet:

The big killers, the infectious diseases, need to be taken care of. It’s not going to be “Check that off the list. We’ve done that.” It’s going to be a concerted effort to catch up. Once caught up, we need to maintain. And that means continuing both identification and treatment efforts. But perhaps, if we’re smart about this, [we will] not have to do it to the entire population but to move to groups that we identify as at higher risk. So, I think the evolution of the delivery system response is something that we can look to that will change the need, but also change the resources needed.

We then turned to discuss the epidemiology of TB in the Asia-Pacific, a region that Dr Goosby describes as “in flux, in terms of our understanding of the burden of disease”. Recent prevalence studies in India and Indonesia, for example, have shown that globally the number of people living with active TB is 10% higher than what was previously believed. Current health system responses need to be strengthened – a task that will require a collective response and regional cooperation:

Countries that are stronger [need] to support countries that are weaker, not only in resources – and resources are important, we need to put more resources into this for sure – but also in technical assistance; training, pre-service training as well as post-; the use of mid-level providers; and the need to engage the community in concretizing and solidifying the response, especially in identification, outreach, and retention strategies.

In addition to the compelling humanitarian and health security reasons to become engaged, Dr Goosby argued that the prevalence of TB in our region also presents Australia with a leadership opportunity:

The intellectual honesty of acknowledging individuals who have not benefited from the science, for one reason or another, to be characterized, counted, and accommodated by leadership, is an act of leadership. And I think that opportunity’s clearly in front of Australia now.

I asked Dr Goosby to expand on how Australian support might be most effectively applied to TB control, which led us into a discussion of the merits of vertical (disease-based) investments in global health. Since the early 2000s, multilateral funds such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and bilateral programs like PEPFAR, have produced dramatic reductions in the number of new infections and the suffering from the diseases they target. These programs were effective in part because:

…[they] allowed the responsibility for response to be shared by rich countries that had the resources, that could come into countries that carried the heaviest burden to help them strengthen their response and maintain it. The knowledge that we gained from that extraordinary mobilization of resources is now congealing in your region around tuberculosis.

He went on to suggest that Australia’s long-term relationships and economic partnerships with countries in Southeast Asia positions Australia to potentially act as a regional convenor. It could lead the development of a strategic plan that brings together funding and expertise to support ministries of health and civil society in those countries to mount a stronger response to TB:

To know the response that they are mounting has this impact, so they understand their investments and the outcomes that they buy, and see defined opportunities for resource and technical assistance infusion, for bringing people to Australia for training, and for a research agenda that addresses the unknowns that are present in these countries but takes the talent that has been trained in Australia to benefit those in the region.

Part of that research agenda will clearly need to include work on multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), which is now responsible for a third of all deaths due to antimicrobial resistance globally:

The treatment [for MDR-TB] is really hundreds of times more expensive. It’s a 50% chance of success, 50% chance of death. And as you acquire more resistance, it drops down to about 20% survival. … So, the costs skyrocketing, the threat to the patient, and the spread of an aerosolized organism that has a good chance of killing you just by you being in the wrong line, or in a play or a movie or a store. Somebody coughs, you inhale it, and away you go.

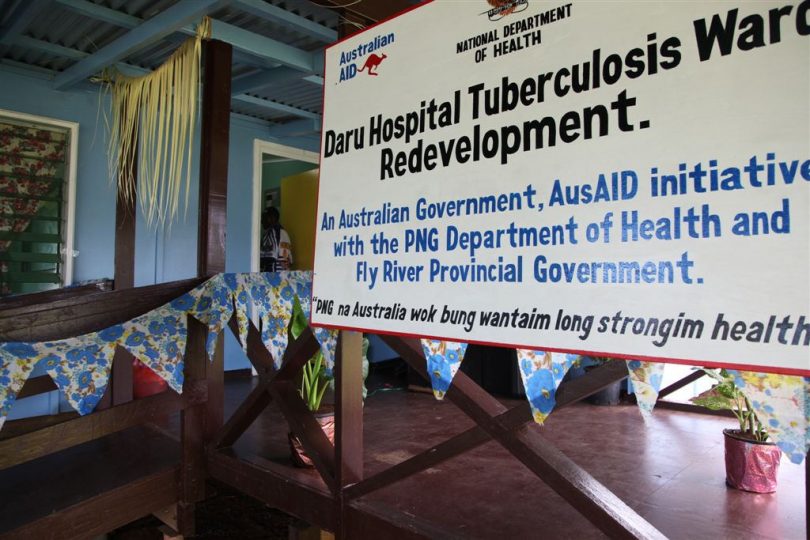

Given the threat posed by MDR-TB and its prevalence in Papua New Guinea, it was great to see the announcement of a new partnership between the Australian aid program, PNG, and the World Bank to tackle MDR-TB coinciding with Dr Goosby’s visit to Canberra, the day after this interview was conducted.

Lastly, I posed the question of what arguments advocates might make to convince the Australian public of the merit of supporting the fight against TB. Dr Goosby suggested that while it’s possible to make an argument based on the instability that TB poses to countries that Australia is in economic partnerships with, there’s also:

the disparity argument; the ethics of knowing how to do something and not doing it. You’ve got to ask yourself, “Why aren’t you engaging on that?” … I think that we do have an obligation to act if we can, and again have to ask ourselves why we decided not to. The counterfactual needs to be on the table as a motivator in and of itself. I think Australia has been sensitive to that argument historically.

Of the arguments,

I think the second argument – being part of the global community, being part of the solution because you can be – is probably the stronger of the two.

Camilla Burkot is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. Dr Eric Goosby is the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on TB. Listen to the podcast here, and read the full transcript here.

Leave a Comment