Development agencies expect a lot from civil society – from providing social services to fighting corruption. It’s little wonder that in 2003 civil society was dubbed ‘the new superpower’ by then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Today, it is considered a key partner in shaping and implementing the post-2015 sustainable development agenda.

With the weight of the world bearing down on its shoulders, it’s important to examine the concept of civil society to get a realistic sense of its potential and pitfalls.

There are two key ways to understand civil society. The first perspective derives from Alexis de Tocqueville’s (1805-1859) sanguine assessment of civil society in the United States during the 19th century. According to followers of de Tocqueville, civil society is an ‘autonomous area of liberty incorporating an organizational culture that builds both political and economic democracy’ (McIllwaine, 2007: 1256; pay walled). In this perspective, civil society is considered a counterweight to, and essentially separated from, state power and market forces.

This approach to conceptualising civil society is reflected by many development organisations. Australia’s DFAT considers civil society as:

a growing range of non-government and non-market organisations through which people can join together to pursue shared interests and values for their communities and nations.

Like many development actors, DFAT writes about civil society in glowing terms, referring to it as an ‘agent of change’. It states that, ‘NGOs [which are often conflated with civil society but are only one component] can be powerful agents for change and are a key development partner’. And DFAT is not alone in this. A recent paper by Bronwen Dalton from the University of Technology Sydney examines the definitions of civil society by a number of think tanks, most of which reflect DFAT’s optimistic assessment.

Yet in many instances, particularly in developing countries, civil society fails to live up to these ideals. For a start, society is often not very civil. We’ve seen that most vividly in Syria, where there is great uncertainty about which groups are civil and which are not. In addition, the boundaries between civil society groups, the state and market are often blurred. Civil society organisations can be co-opted by the state, such as those coined Government Organised NGOs (GONGOs), which are dependent on government funds. The private sector can also significantly shape civil society organisations, reflected in the categorisation of Business Organised NGOs (BONGOs) and Business Interested NGOs (BINGOs).

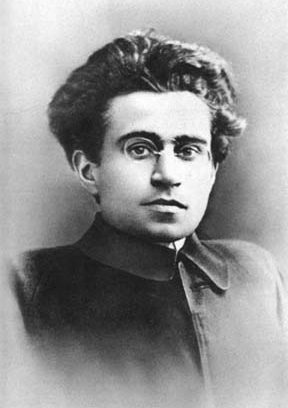

These conceptual issues have led some to draw on insights from Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), whose writings focused on three aspects of civil society, differentiating his analysis from de Tocqueville’s. First, he stressed the fluidity of relations between the state and civil society – arguing that as civil society (trade unions, media, religious organisations, etc.) and political society (police, army, legal system, etc.) often overlap, one cannot be understood without the other. Indeed he conceived the state as comprising both civil and political society. Second, Gramsci argued that civil society consists of elements that resist or reinforce hegemonic ideas about economic and social life. For Gramsci, civil society is a jumble of groups whose ability to benefit society is dependent on context and the nature of dominant ideas.

Finally, Gramsci was also concerned with international forces. Social theorist Bob Jessop’s insightful analysis shows how Gramsci believed that: ‘national states are not self-closed “power containers” but should be studied in terms of their complex interconnections with states and political forces on other scales’ (2005: 425). Other scholars, particularly geographers, have used this insight to study the interconnection between local and international civil society groups. Some suggest that these interconnections help social and environmental movements, while others disagree.

Gramsci was a Marxist, and considered the role of civil and political society in terms of class relations. So it’s not surprising that his theory of civil society is less drawn upon by development agencies than de Tocqueville’s, who was a classic liberal.

However, some believe that the world of development is starting to take a more ‘Gramscian view’ of civil society given some of the failures of policies aimed at supporting civil organisations.

Human geographer Cathy McIllwaine writes [pay walled] that:

the role of civil society in the development policy arena has moved from one of adulation to one of much greater circumspection about what they can actually deliver in practice (2007: 1262).

She believes this ‘falling out of love’ with civil society could be considered a shift towards a ‘more realistic Gramscian interpretation of civil society’ (2007: 1263).

Attempts to deal with both the uncivil and civil elements of society are reflected in policy discussions about anti-corruption movements. Transparency International’s influential Source Book – a guidebook used by a range of policy makers and activists around the world – cautions that:

Many civil society groups are single-minded in the pursuit of their particular cause and have no interest in balancing their aspirations within the wider public good (Ch 15; p. 131).

It also notes that the organisation will only work with groups that are ‘expressly non-partisan and non-confrontational’ (p. 135) – an approach that attempts to separate civil society from the political dimensions of the state.

Neo-Gramscians would support efforts to identify civil and uncivil elements of society, but many would question whether civil society can be as ‘non-partisan’ as this document suggests. Indeed, in this edited volume, academic Luis De Sousa notes that, despite its apolitical orientation, Transparency International has involved politicians in their local chapters and requires state support for their continued operations. Anti-corruption advocacy ultimately requires engaging with politicians and politics – which can mean taking a political side (even if actors try to appear non-partisan). It’s difficult to extract politics from advocacy.

This example highlights how some of Gramsci’s concerns have been reflected in development policy while others have been side-stepped.

Empowering civil society to promote social change is fraught, and raises many of the issues that Gramsci was concerned with almost a century ago. Given the importance development actors place on supporting civil society, practitioners could benefit from thinking through the insights offered by this Italian Marxist. Even if they don’t agree with his politics.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

Thanks Grant for your blog. Most of us who have worked for a significant time around civil society in the developing world, and donor attempts to sponsor civil society, become aware of the inherent contradictions, and your exploration of the different theoretical approaches to civil society – e.g. Gramsci v. De Tocqueville, give us useful food for thought around these issues. To me, the ‘non-partisanship’ of groups like Transparency International was always an expedient operational approach and a useful guide to practice, rather than a deep-seated philosophical position. Of course, nothing upsets the existing balance of power within a given society than ‘fighting corruption’, unless the fight is completely ineffectual, and thus it is an essentially ‘political’ fight in the ‘big P’ sense, and not the petty grasp for power by individuals in the ‘small p’ sense. In my view, TI is clearly trying to expressly distance itself from the latter, whilst quietly associating itself with the former. TI also tries to avoid the most heated partisan fights by trying to take the long-view (no naming and shaming!), and thus keeping their hands relatively clean. I don’t think this renders either the work of TI or donor support of TI fundamentally flawed or contradictory, but it’s definitely sensitive territory and needs to be approached with context awareness and nuanced scholarly understanding – two things which are not always in plentiful supply. But there’s another connected point that I’d be interested in your views upon – that is, the alien nature of civil society in a largely non-industrial and subsistence-based society. As we know, part of the under-performance problem of civil society in a country like PNG is that the civil society groups that look most like de Tocqueville’s version are mostly urban-based, donor-sponsored and struggle to connect to the rural masses, and most scholars would agree that without the complexity and scale that comes with mass industrial society, civil society as we know it isn’t possible. To get to the point, do you think civil society exists in the rural villages of Papua New Guinea? Or is it a social phenomenon that can only exist within large-scale, inter-connected, industrialized, urban societies?

Marcus, I don’t think that de Tocqueville’s or Gramsci’s conceptions of civil society require industrialisation per se. PNG has numerous civil society groups (churches, NGOs, etc) and it’s not really industrialised. The rural and remote areas of PNG do have civil society groups that are active, although they are more fragmented than in other parts of the world. The interconnection between local and international civil society groups, and the PNG state, is more likely to occur in urban areas, but is not constrained to cities.

In the rural areas of PNG, there needs to be a greater focus on how civil society groups are engaging with political society at the district level, given the moves to decentralise decision making and massively increase constituency funds. Gramsci would want us to understand how civil society might be complicit in both supporting poor governance and promoting accountability. And what civil society groups’ connections to politicians and bureaucrats means for their capacity to empower citizens (he wanted to see citizens empowered for the revolution, but I’d settle for stronger and more equitable democracy…).

Also, you may be interested in a blog I’ve just published on the affair of the IACC and the Malaysian PM. It further highlights the difficulties of claims about non-partisanship among international anti-corruption actors.

Thanks for the referral to your other very good blog Grant. It may be true then, what I was told some years ago – “when you sup with the devil, use a long spoon.” – when we were trying to fashion an approach to an invitation from a politician that had a public reputation for “corruption”, (whatever that means). To me, your example from your other blog of the Malaysian PM highlights the complexity of the issues around corruption, and that progress is made primarily in the political arena of local vested interests and competing identities. No area of public policy advocacy rewards purists, and compromise between powerful interest groups is an essential aspect of policy forward movement. I think it’s necessary for the anticorruption movement to engage with pollies, because it’s an essentially political fight. But who they engage with, and when, is a matter of judgement that is best made by those who will bear the consequences of getting it wrong. Whether TI has made the wrong call in engaging with the Malaysian PM, and then disengaging, is impossible to tell right now, but I think that anticorruption advocates will need to keep “supping with the devil”, if they are to make progress. I can recall another quote from Gough Whitlam that I think is relevant to this point – “only the impotent are pure”.

To your other point in your blog about target audiences and the costs of attending conferences, I definitely agree that events such as the IACC, like most international shindigs, are beyond your average grassroots advocate, as well as academics, and are worse off for it. And when one considers that many attendees are public servants employed by governments (with their attendance funded by the same), then one can legitimately question the personal fervour of many of those who end up there, which is galling when one knows there are countless grassroots anticorruption advocates around the world who would give their right arm for the chance to go to an IACC conference. However, at the end of the day anticorruption progress is mostly about coalitions, and TI would seem to me to have their broader approach about right at least in that regard, even when the IACC doesn’t quite hit-the-mark.

Thanks again for your excellent blogs.

Beyond Gransci……

The civil society expresses itself through multiplicity of groups or collectivity attaining diverse objectives. Quite often some of them work as pressure group in the governing process. Such groups and organisations are vertically active from local to the international level and horizontally they are issue and sector specific. Whatever their nature and role may be, they important component of the structural and institutional character of the society. Grant Walton has rightly classified as GONGOs, BONGOs, BINGOs, International NGOs and other Socio-Cultural organisations. They may serve educative, advocacy and developmental purpose or motivate for political action. Certainly they are playing an important role around the world but recent trends indicate that suspicion is being raised about their character as civil society as being non-partisan and apolitical. China, Russia and India are raising suspicion particularly about the international NGOs and contemplating to impose some restrictions on their activities or even ban their operation. It may diminish the role of NGOs as civil society and impose limits on the social enterprise. It appears these countries used the civil society organisations to get connected with civil society in the developed world but now resistant when these civil society organisations started generating awareness among the masses through their educational, advocacy and developmental activities. It is likely to adversely affect the interest of the elite section and their domination may be liquidated in the highly structured society in these countries. There is sufficient evidence that the role of civil society is being diminished in these countries and there are concerted efforts to make the civil society subordinate to the State and Market. Such a trend in these countries will have global impact during next two decades. It may compel one to raise skepticism and suspicion about the realisation of SDGs by 2030.