In this post for the Aid Open Forum, Richard Curtain continues our series of articles looking at the latest Annual Review of Development Effectiveness. The other articles in the series can be found here.

Is Australian development aid effective? The answer is yes in a narrow sense of delivering programs, but in terms of impact on poverty we do not know in any systematic way. As AusAID’s own watchdog, the Office of Development Effectiveness, notes in its just released Annual Review for 2009:

AusAID does not have an overarching strategy on implementing the aid effectiveness agenda and has not clarified how to report against aid effectiveness principles. It needs a strategy for reporting that sets out benchmarks and targets for country and regional programs in terms of aid effectiveness principles.

In terms of sound public policy, we need to be first clear about what the aid program is trying to do, and how is it trying to do it. Once this is clear, we can work out whether it is succeeding. If it is not succeeding, we need to know how will changes be made?

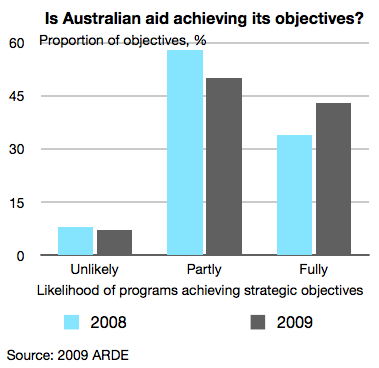

The Review reports the self-assessments of program staff. These show that only six per cent of the program’s strategic objectives are unlikely to be achieved within their timeframes. But, as an appendix acknowledges, many of AusAID’s country programs are operating without strategies or clear indicators or targets to measure performance so this makes it extremely difficult to measure the aid program’s broader impact. ‘Program areas tend to recognise or articulate success only in terms of whether the majority of individual activities in their portfolio are performing well—not in terms of, for example, the performance of policy dialogue and country-level objectives.’

So the Review departs from past practice to look more closely at the bigger picture affecting a subset of aid activities – the delivery of services to the poor. Evaluations of aid effectiveness were undertaken in three key service sectors in a range of countries: basic education, health and water and sanitation. The key question is whether the in-house watchdog is bold enough to identify basic problems with the current system of aid delivery. Telling only part of the story will not produce major change if the analysis does not go far enough.

The Review highlights five lessons from these evaluations for the future delivery of aid. But in each case, the lessons do not dig deep enough. First, we are told that AusAID staff need to develop a better understanding of each country in which they work. Good technical assessments of the challenges are not enough. More important is ‘effective engagement, including robust policy dialogue built on mutual respect’.

AusAID has Pacific Partnerships for Development agreements with eight governments about future aid flows and commitments. But the Review notes that the agreements have achieved little in terms of putting the partners ‘in the driver’s seat’: ‘it is too early to assess whether the changes brought about by the partnerships will improve the situation in those countries that have them’. But the only reason given for assessment is that the ‘institutional issues had not been addressed adequately’. We obviously need to know more about what these institutional issues are to work out why they are limiting the effectiveness of these agreements.

The second lesson is that AusAID needs a clear strategy to work with partner countries’ budget and procurement systems. Only 40 per cent of Australia’s aid is disbursed using national budget systems, short of the OECD average of 47 per cent. Only 23 per cent of Australia’s aid is disbursed through government procurement systems, much lower than the OECD average of 44 per cent and far below the OECD target for 2010 of 80 per cent.

It is not enough for AusAID to claim that fragile states do not have adequate systems. The Review faces squarely the problem of AusAID’s own bias against using government systems to disburse aid. Concerns about fiduciary risk override other important considerations such as the risk of failing to deliver development results and upholding Australia’s reputation as a reliable donor. The proposed response, however, is merely to ask senior AusAID managers to give clear messages to staff to work out strategies for managing these different types of risk. Missing is a deeper analysis of why these senior managers have not been doing this to date.

The third lesson is the gap between the policy and the practice in relation to gender equality: ‘while gender equality has been built into many activities, it is usually peripheral and rarely sustained’. Progress in achieving gender equality is often not even monitored, due to a lack of gender specific data. This begs the question about the poor internal processes which have failed to pick this up early in the life of a program.

Sustainability concerns were identified in each of the three service delivery sectors examined. The Review notes that sustainability depends on longer-term financing from donors or government, acceptance of responsibility by government and the community for maintaining the asset and the environmental impact. However, we are not given any data on the funding cycle of AusAID programs? Do these cycles vary between countries for the same type of programs? If so, what are the reasons for this?

Finally, AusAID is urged to place greater emphasis on managing for results. The Review notes that the agency demands accountability from recipient governments but itself has weak systems of monitoring results and in using evidence to change its own practices. Again this begs the question of whether answering to an internal watchdog lets AusAID off too lightly? Why not ask AusAID to develop a small number of simple performance indicators related to these issues for each beneficiary country? To give credibility to these measures, independent body such as a well-resourced parliamentary standing committee needs to be set up to monitor the agency’s performance.

Aid effectiveness has to be more than delivering on narrow program objectives. In many countries in the region, aid dependence has produced resource curse effects. This causes governments and citizens to both lack the political will and the capacity to reform basic services such as education and health. An effective aid program in a weak state has to address this problem and provide evidence that it is doing so.

The delivery of aid needs to be radically transformed from how it operates now. A major circuit breaker is needed to reverse entrenched practices. Incremental changes cannot overcome the force of mutually reinforcing perverse incentives. The whole system of aid delivery has to change.

AusAID has to give first priority to working with country stakeholders to produce long-term development outcomes. This has to replace the narrow accountability to Australian taxpayers of minimising fiduciary risk. The concept of cash-on-delivery aid aims to reverse these perverse incentives. Asking an aid-dependent government to accept responsibility for delivering a development outcome and to accept the consequences if they do not is the sort of transformation needed. However, setting up pilot programs to trial the concept will have little impact on how AusAID functions. More fundamental reforms are needed.

Richard Curtain is a Melbourne-based, public policy consultant, who has spent 18 months in Timor-Leste in 2008 and 2009, working on projects funded by USAID, UNICEF and AusAID. His current work for two major multilateral agencies in the region relates to Timor-Leste and to pacific island countries.

Leave a Comment