In Solomon Islands the night before elections is known as Devil’s Night. A night of misdeeds, when candidates’ support teams bustle and jostle around electorates in trucks and outboard motor boats buying votes.

The name Devil’s Night is an evocative Solomon Islands twist, but vote buying itself can be found across the developing world. It’s common, but also a puzzle: where ballots are secret (as they seem to be in most cases in Solomon Islands), there is nothing to stop voters from taking money and voting for someone else. And sometimes, quite often perhaps, this is what they do. Yet vote buying must at least work to an extent; if it didn’t it is hard to imagine why candidates would continue to waste their money.

In Solomon Islands vote buying appears to work in a range of ways.

Sometimes vote buying takes the form of what Simeon Nichter calls turnout buying: candidates pay the transport costs of Honiara residents who are registered in the rural constituencies that the candidates are contesting in. When they do this they focus on paying the fares of people from their church (sometimes) or village, or extended relatives – people who will likely vote for them if they are back in their electorate (votes must be cast within electorates).

And sometimes vote buying works simply because voters are grateful for the money, and feel like it would be morally wrong to defect on the implicit contract involved. At other times it works as a signal, allowing a candidate to provide evidence of their propensity to help should they be elected.

Sometimes vote-buying works not by buying the support of voters themselves but through buying the support of influential local leaders. This sort of vote buying usually takes place quietly and well before the election but it is probably the most powerful: either by persuasion or coercion these sorts of figures can often deliver somewhat cohesive blocs of votes.

Beyond its interaction with vote buying, the coercion of some voters is a problem in its own right. A lot of Solomon Islands voters are free to choose, but not everyone. Just like vote buying, coercion ought not be possible in the presence of a secret ballot seems to be enabled both by voters not being 100 per cent confident their ballot is secret (and therefore not willing to take the risk) and also through voters not wanting to disobey authority figures.

Related to vote buying is violence. Electoral violence in Solomons is not nearly as large scale or as serious as in many countries. (Indeed, that the two elections post the civil war have been largely violence free is a testament to the skill of Solomon Islanders in mediating local conflicts.) But violence does occur – campaign teams fight, houses are sometimes burnt, voters are sometimes openly threatened and polling stations or counting places sometimes attacked.

Related to vote buying is violence. Electoral violence in Solomons is not nearly as large scale or as serious as in many countries. (Indeed, that the two elections post the civil war have been largely violence free is a testament to the skill of Solomon Islanders in mediating local conflicts.) But violence does occur – campaign teams fight, houses are sometimes burnt, voters are sometimes openly threatened and polling stations or counting places sometimes attacked.

Vote buying, voter coercion, and the possibility of violence: taken together they sound grim. But it isn’t the full picture. Most voters don’t sell their votes. Many (probably most) voters are free to decide who to vote for. And violence may haunt elections in parts of the country, but its actual appearance is rare.

What is more, Solomon Islands has done an admirable job of actually running elections themselves quite well. Not perfectly but given the challenges involved – a low capacity state, a country sprawled across island groups, tiny islets and remote inland villages – pretty successfully. Ballot boxes make it out and back, cheating within polling stations appears quite rare, and counting is open and fair.

None of this is inevitable, as the problems of elections in other countries show, and it is an achievement.

So what does this all mean for the elections on the 19th?

Much of the same plus a few new twists – many in some way related to the compilation of a biometric voter roll earlier this year. The new roll replaced an old, inflated one, and appears to have reduced double registrations considerably. It also came with voter ID cards which voters are encouraged (but not forced) to use when voting. The new roll appears much better, although there has been a lot of talk of powerful candidates paying voters to register in the candidates’ constituency rather than in the constituency where the voter lives. As well as talk of candidates’ agents busily buying voters’ ID cards.

And, associated with this, out on the campaign trail vote buying is already underway. Intriguingly, whereas in the past, most of the turnout buying has involved voters being shipped from Honiara to rural constituencies. This time, alongside the compilation of the new roll, there is now a lot of talk of powerful Honiara candidates transporting voters to Honiara – first to register and then to vote. In many ways this makes sense: Honiara is home to a lot of money, and it is very hard to prove that someone is not a resident of the city and therefore ineligible to be registered there.

And, associated with this, out on the campaign trail vote buying is already underway. Intriguingly, whereas in the past, most of the turnout buying has involved voters being shipped from Honiara to rural constituencies. This time, alongside the compilation of the new roll, there is now a lot of talk of powerful Honiara candidates transporting voters to Honiara – first to register and then to vote. In many ways this makes sense: Honiara is home to a lot of money, and it is very hard to prove that someone is not a resident of the city and therefore ineligible to be registered there.

Harder to fathom is the buying of vote cards: voters can vote without them; and they have photo ID’s on them, which would mean, absent assistance from polling officials, it won’t be possible to use them to impersonate voters. The best explanation I’ve heard for their purchase is that candidates’ agents have bought the cards with the plan of returning them to voters on the day of the election. And they have done this to stop voters from selling their votes to multiple candidates, and also as a way of reminding voters, at the last minute return of the card, just who they took money from, and who they owe loyalty to as a result.

Voter coercion will presumably occur as it always has (I’ve heard nothing to suggest otherwise) and small scale violence associated with the elections is likely. In particular, there are some hard fought campaigns in Malaita and in the North and East of Guadalcanal. There has also been the violent split of the Christian Fellowship Church in the Country’s Western Province, which appears very likely to lead to confrontation amongst the church splinters and their candidates.

Hopefully, all of this will stay manageable. And that the logistical feats that have seen the running of previous elections go tolerably will be repeated (I think they will, though nothing logistical is ever 100 per cent certain here).

Problems being managed, and elections running ok won’t solve the underlying issues of Solomon Islands politics, nor do these successes negate issues like vote buying. But the things that do work in Solomon Islands elections help, at least, hold the window of democratic space open for local solutions to emerge through, and in the long run that matters.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His PhD focused on Solomon Islands electoral politics. Prior to study he worked for the New Zealand Government Aid Programme.

hi Jon, thanks for your comment.

Two points of agreement and one of disagreement

I agree: last minute vote buying is not a Solomons only phenomenon (indeed I say so in the second paragraph).

I disagree: the term devil’s night is only restricted to the night before the election; it isn’t used for voters seeking personal benefit more broadly.

And I agree: villagers voting for personal or localised benefits is completely logical given the state of the state in Solomons.

cheers

Terence

Hi Terence, You are missing my main initial point. This was to suggest some greater critical scrutiny of Honiara elites complaints about ‘devil’s night’ (last minute vote-buying before a general election), not to question when exactly vote-buying occurs. Articulate, reformist Western-centric or church-going candidates often raise these objections against victors who dabble in money politics, but when you scratch the surface the difference in campaign styles at least of the victors is often not that great. Losers of course almost invariably complain that they were outwitted by cheating. English-Speaking and overseas educated candidates know that expatriates will often be convinced by their claims because so many expect to find corruption pretty much everywhere in Melanesia.

Hi Jon,

Thanks for the clarification.

You wrote: “The phase [Devil’s Night] is a euphemism for the short-termism of rural constituents.” I disagree with this: I think the phrase simply refers to vote buying in the immediate lead up to (and especially the night before) elections. Although I do agree that voter preferences for localised and/or personalised gain are something that are discussed (and at the elite level often lamented) by Solomon Islanders when they analyse their politics.

Beyond that, as I said in my earlier comment, I agree with you that villager’s choices make sense given the circumstances they vote in.

I also agree with you that most major candidates, be they ostensible reformers or not, appear to engage in vote buying & patronage politics (there is also a logic to this, as I noted in my earlier post). As for whether expatriates are beguiled by the claims of overseas educated candidates or not, this isn’t something I know much about, or am interested in — not my subject area, although I’ve always thought an ethnographic study of expat life in Honiara would make for good anthropology.

In my case, as you know, my claims about electoral politics are based on results data, survey data and case studies of Solomons constituencies.

Thanks for the comments.

Terence

Thanks tufala for this interesting exchange.

I’d maintain that the notion of “beguiling narratives” applies as much to our own Solomon elite and youth as to expats (…and both areas would be a rich basis for anthropological work).

A key element of these narratives is the recurrent trope of national renewal manifested by “new blood” and “new leaders”. As social media has spread, the rhetoric and discourse employing this trope has been easier to observe, but it has been in strong evidence at least as long as the end of the tensions. In 2006, the “Winds of Change” campaign was the most visible instance of this.

It has been particularly evident this time around in online discussions, during both the leadup to the election and the letdown periods. The former during the buildup and campaign period, and the latter in the past 48 hrs as the news of incumbents prevailing, keeps rolling in. Facebook has permitted direct observation of people bemoaning (in a public forum) the behaviour of the general voting population in violating the expectation of mass change. In the past this might have formed a part of the private lament of [ostensibly cheated] candidates seeking to explain their losses.

The 2006 riots were I believe enabled by the wide variance between on the one hand, the public expectation of a national revival a’ la Winds of Change, and on the other hand the perception of continued politics-as-usual when Rini was elected PM. Although it is hard to compare 2006 to now, the online atmosphere today does seem to reflect more nuance and reflection than previously on display.

The tempering of these narratives is important for stability during the post-election period, and for workable political settlements in the immediate aftermath, but this is a difficult call when such grand and -evidently- unattainable narratives are an important element of political mobilisation for many reformist candidates and groups.

Thank you Paul, that is a very interesting comment.

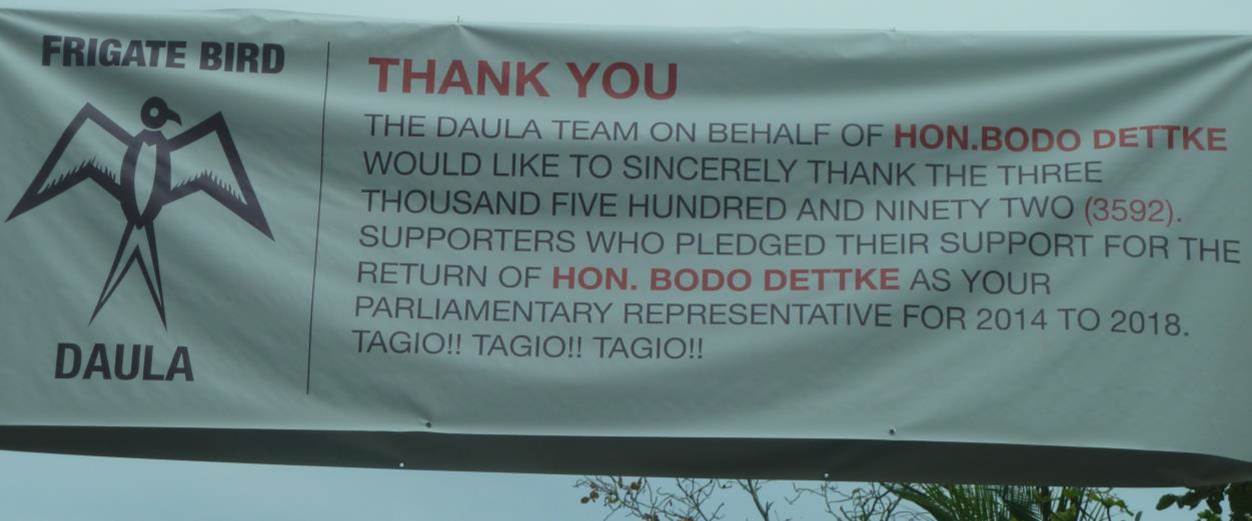

I was intrigued to see how often the word ‘change’ appeared on people’s campaign posters (in the Honiara and small set of rural constituencies I visited this time round).

It’s also interesting that, as you note, it also appears to be becoming a very good election for incumbents (a product I guess of relatively high GDP growth since the last election, plus increased RCDF money, and a last minute grant MPs awarded to themselves adding up to more money in politics, and – in particular – available to incumbents, although this is just a guess).

And thank you – that is a very interesting comment on the role of Facebook.

Thanks again

Terence

Spot on Paul! The ‘winds of change’ of change stuff back in 2006 also had some weird religious links with the moral majority crowd. Yet the ‘beguiling narratives’ you mention also surely convey or reflect a potentially explosive mismatch between urban (& urban youth) expectations about new governments and the inarticulate results of the rural voting patterns, which exert the predominant influence over the composition of parliaments. The trouble is that changing winds tend to bring new cohorts of politicians to office that very much resemble their predecessors (or at least do so when they operate as a collectivity on the floor of parliament), rather than bringing to bear some generational change that might alter established patterns of governance. Its strange to hear various media outlets reporting a low incumbent turnover rate as big news because, though that may be unusual for Solomon Islands (excepting 1993 when Mamaloni opened the purse strings), the proportion of MPs who lose their seats tend to be much lower in the industrialised or richer countries or even to the east in countries like Samoa. Cheers, Jon

Thanks to all, this has been an interesting exchange.

Jon,

Could you clarify your last point in your most recent comment? If the Solomon Islands have typically had a high turnover of incumbents in the past, why is it strange that the media is reporting a low turnover rate this time around? Seems like it would be quite newsworthy and possibly an interesting change in political dynamics (particularly, as you say, low incumbency turnover is often the norm elsewhere).

Regards,

Stephen

Hi Paul,

Can I ask about the role of Facebook or other social media more generally… are these also popular for use outside election time to discuss ongoing political issues and controversial decisions? Are they particularly captured by specific groups or campaign interests or are there useful forums that engage more independently that are worth watching?

Thanks for the above to everyone – really interesting comments.

Cheers

Beth

Thank you Beth,

Just a quick response in case Paul is no longer checking the thread: the central facebook forum, FSII, has covered a lot of non-election-related political stuff as well. And they have, in my opinion, done a very good job of staying neutral and not being captured, which would have been challenging. However, around the periphery of FSII other social media based groups have, I think, been involved in more partisan ways – which is perhaps (but not inevitably) more problematic.

Terence

Terence – for sure, there is evidence of ‘devil’s night’, entailing last minute payments to communities to capture their votes (shorn of the Christian symbolism, something almost identical is identified by Ed Aspinall in Indonesia), but there are also a lot of candidates and Honiara elites who complain a great deal about ‘devil’s night’. The phase is a euphemism for the short-termism of rural constituents. The candidates who complain about this imply, accurately or inaccurately, that they have been playing a long game, but are being outwitted by the unscrupulous and corrupt ‘Mamaloni men’ who nip in at the last minute to entice the unsuspecting constituents with baubles. Are villagers really so short-sighted? Or is it the case that there is in fact very little filtering down of much in the way of development to the villages, and so constituents logically try to obtain the short-run gains close to the election-time?

Jon