First published by the University of PNG Press in 1985 with a second edition published in 1994, this book remains important foundational reading for anyone interested in issues of social safety, and family and intimate partner violence in PNG. With new laws passed in recent years to address family violence (Family Protect Act 2013) and other family issues such as the rights of children (Lukautim Pikinini (Child) Act 2009 [amended in 2014]), this book also provides a baseline for understanding the historical and social context for the transformation of family law in PNG.

A core theme of the book is the complex interactions between statute and customary laws in PNG that give rise to legal pluralism, and the significance of these for family law. Chapter 1 provides a succinct introduction, emphasising the book’s focus on marriage and de facto relationships, breakdowns in marriage, financial claims, and custody and adoption of children. Marriage, and the distinctions between statutory and customary marriage, is discussed in Chapter 2 and the issues are developed throughout the book. In Chapter 3 the authors examine how laws are applied in cases of marital breakdowns and divorce. Domestic violence is highlighted as key reason for, or outcome of, marital disputes that need to draw on the law for the protection of members of the family. The discussion draws on the important investigations undertaken in the 1980s by the Law Reform Commission into domestic violence. Depending on the form of marriage – statutory or customary – different laws and court jurisdictions apply. This makes it difficult to address marital disputes, divorce or even domestic violence in a uniform manner across the country.

The array of financial claims that are possible in marriage or in divorce are discussed in Chapter 4. This covers customary claims such as bride price, damages relating to adultery, maintenance of children, property (including married women’s property), and financial separation and maintenance agreements. In Chapters 5 and 6, custody of children and adoption of children are examined respectively. The book concludes with a discussion about a number of proposals for legal reform, some of which have since been realised. For example, emphasising the work of the PNG Law Reform Commission, the book highlighted the need to address domestic violence in legislation. Despite these recommendations having been made in 1985, the Family Protect Act was only passed in 2013, nearly 30 years later.

As someone who does not have a legal background but who is keenly interested in issues of social justice and family protection, the value of the book for me lies in the nuanced yet accessible examination of concrete case studies to demonstrate the difficulties of applying laws, and the confusion and inconsistencies that can arise as they overlap in the PNG social setting. It also demonstrates the various tiers of courts and their associated jurisdictions that people have to navigate when dealing with family disputes that require legal recourse. Laws such as the Customs Recognition Act, the Village Courts Act and the Marriage Act, just to name a few, interconnect depending on the case at hand, and have real consequences for how disputes are handled by different courts. These things matter in PNG where local customs vary widely, where there is increasing inter-cultural marriage, increasing population mobility, and where access to legal support is limited. Furthermore, reflecting PNG’s colonial history, much of statutory law is transplanted from Australian law. One outcome of this colonial legacy is that PNG’s statutory family law tends to emphasise nuclear style families rather than reflect the social lives and customs of PNG families.

This is an important book that needs to be updated and complemented with further publications based on more recent developments in family law in PNG. This is important because of the persistence of gender inequality and violence against women, and the pace of social change occurring in PNG. Furthermore, given that new laws have been introduced, a new publication should emulate the approach of this book to present a nuanced discussion of the outcomes, unintended consequences and inconsistencies in new legislation. For example, two questions that arise include: How are recent laws like the Lukautim Pikinini (Child) Act and the Family Protection Act being implemented in the context of PNG? How will the pikinini courts (children’s courts) envisaged under the Lukautim Pikinini (Child) Act interface with the existing and prevalent village courts?

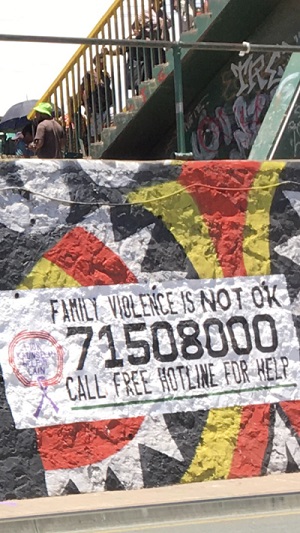

Another major positive development in PNG in recent years has been the establishment of services such as women’s refuge centres, case management centres and Family Sexual Violence Support Centres in police stations to support families and victims of violence. The experiences of these service providers are an important part of understanding how laws are implemented in PNG. For example, how do local customs determine the provision of services and the outcomes for families, children, and victims of violence? What are the unintended outcomes for children, women, and families? How do these all overlap or come into conflict with the Customs Recognition Act? Without an analysis of concrete case studies these questions will be difficult to answer. A wealth of anthropological, developmental, media and other social knowledge have also been produced since the book was published, and these need to be reflected in contemporary discussions about family law.

This book appeals to a wide audience because, while critically interrogating PNG’s family law, one of its key strengths is that the case study material it analyses draws from a variety of sources including anthropological studies, legal cases, the media, and even ethnographic films. As with many issues in PNG, this highlights the need for an interdisciplinary approach to understanding social issues. As PNG society continues to transform, family law will remain critical. Reading this book is important as is ensuring that an updated version and complementary publications are produced.

Owen Jessep and John Luluaki. 1994. Principles of Family Law in Papua New Guinea (2nd ed.) Port Moresby: University of Papua New Guinea Press.

Michelle Rooney is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

The Customs Recognition Act has been partly repealed by the Underlying Law Act 2000, although the extent of the implied repeal is a matter of debate.