The Human Development Report (HDR) is the annual report of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) which, twenty years ago, launched the Human Development Index (HDI), a composite index which judges countries’ performance by their per capita income, literacy and average life expectancy. Much of the discussion around the 20th annual HDR, released last year, has been around some controversial changes to the HDI proposed in it.

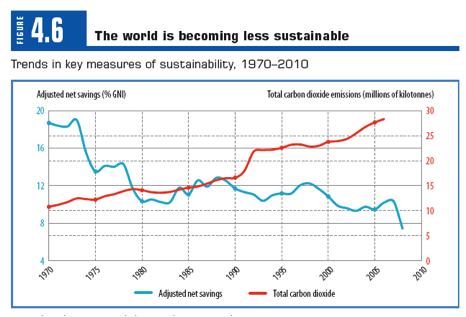

The next HDR is going to be about sustainability. It’s a subject touched on only briefly by the 2010 Human Development Report, but in alarming terms. Figure 4.6 of the HDR (reproduced above) shows that global sustainability (as measured by adjusted net savings) is falling. It also has a second line which shows that emissions of carbon dioxide are rising. The idea behind the graph is explained in the text: however you measure it, the world’s sustainability is at risk, and climate change is a major culprit.

The only problem with this argument is that, while it is true that adjusted net savings (or genuine savings as it is sometimes called) has been falling, this has nothing to do with carbon dioxide emissions rising. To calculate adjusted net savings, the World Bank, which is the source of the data the HDR uses, starts with the national accounts, and adjusts them in various ways to derive a broader view of savings, one that acknowledges that our future prosperity depends not only on how much we save, but on how much we educate our children, how much we deplete our natural resource base, and how much we pollute the planet.

The Bank publishes not only the adjusted net savings, but also its various components. As this figure on the right shows, in fact CO2 damages (the climate change ‘penalty’ calculated by the World Bank to derive adjusted net savings) is not only low but has been falling over time. Adjusted net savings have indeed also been falling, as the HDR graph shows, but this is mainly because global financial savings have been in decline and, recently, because high oil prices have increased the value of the ongoing depletion of global oil resources. So, if you believe the World Bank adjusted savings figures, and are worried by them, you should be concerned not about climate change but about getting national savings rates up, especially among oil-rich countries.

The Bank publishes not only the adjusted net savings, but also its various components. As this figure on the right shows, in fact CO2 damages (the climate change ‘penalty’ calculated by the World Bank to derive adjusted net savings) is not only low but has been falling over time. Adjusted net savings have indeed also been falling, as the HDR graph shows, but this is mainly because global financial savings have been in decline and, recently, because high oil prices have increased the value of the ongoing depletion of global oil resources. So, if you believe the World Bank adjusted savings figures, and are worried by them, you should be concerned not about climate change but about getting national savings rates up, especially among oil-rich countries.

This raises some interesting questions, as my colleague Paul Burke has recently noted in his (gated) review of the underlying World Bank work. If the future damage of climate change is equivalent to just a one per cent reduction in the savings rate, you’ve got to ask what all the fuss is about. On the other hand, if you think climate change is a threat to sustainability then you also have to think that the $20 per tonne ‘shadow price’ (estimate of damage) which the World Bank attaches to CO2 emissions is much too low.

Quantification of climate change damages and risks is fraught. In my view, the World Bank is much too conservative. The threat climate change poses to our sustainability is evident simply from the temperature increases which would flow from the continuation of the current trajectory of rapid emissions growth. As the 2008 Garnaut Review showed, the result would likely be a temperature increase of some 5 degrees Celsius over the course of the century. Such large increases in temperature would in turn, as Garnaut put it, “not lead to a marginal reduction in human welfare. Their impacts on human civilization and most ecosystems are likely to be catastrophic.” (p. 263).

So, yes, climate change does “pose serious questions about the long-run feasibility of the world’s current global production and consumption patterns,” as the 2010 HDR argues (p. 82), provided that the savings data which the HDR uses to make this point is wrong.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Crawford School of Economics and Government, ANU.