This exploration of scholarships in the Australian aid program comes in three parts. The first looks at the context of Australian aid-funded scholarships. The second reveals results from a DFAT-funded study of scholarship alumni in Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda (funded under the Australian Development Research Awards scheme). The third explores possible future challenges and directions for scholarships as a central pillar of the Australian aid program.

Part One: Scholarships and their place in the aid program

Scholarships are a large and growing part of the Australian aid program. In the 2007/08 budget, almost $100m was spent on scholarships, making up 5% of Australia’s total Official Development Assistance (ODA). In the 2014/15 budget, $310m has been allocated, representing 6% of total ODA. ‘The 2014-15 development assistance budget: a summary’ affirms that Australia will offer more than 4,500 scholarships and fellowships to “build skills to contribute to economic and human development and foster links between Australia and countries in our region.”

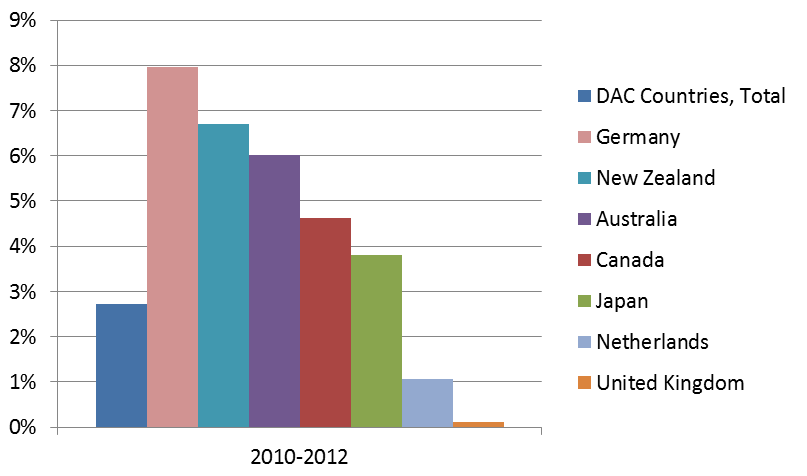

Using OECD DAC data, we can see that Australia has spent more on scholarships as a percentage of total ODA over 2010-2012 than comparable donors such as the UK, Canada and Japan.

What exactly are scholarships, as provided by the Australian aid program? Most would immediately think of support for masters level study at Australian universities with funding for tuition, living expenses, visas, flights and health cover. Scholarships also cover some PhDs at Australian universities. In addition, there are an increasing number of short-term fellowships offered, whereby individuals from low and middle-income countries (LMIC) study and receive professional development in Australia for two weeks to twelve months on a specific topic, without completing an accredited degree. The Australian aid program is also now offering short courses delivered in these countries.

What exactly are scholarships, as provided by the Australian aid program? Most would immediately think of support for masters level study at Australian universities with funding for tuition, living expenses, visas, flights and health cover. Scholarships also cover some PhDs at Australian universities. In addition, there are an increasing number of short-term fellowships offered, whereby individuals from low and middle-income countries (LMIC) study and receive professional development in Australia for two weeks to twelve months on a specific topic, without completing an accredited degree. The Australian aid program is also now offering short courses delivered in these countries.

Given the prominence of scholarships as part of the aid program, it is important to examine the various benefits and critiques of this approach to aid delivery.

Scholarships clearly provide a tremendous and life-changing potential opportunity for individuals from LMICs to learn new skills and apply them at home. Thousands of young people from around the world have studied in Australia and gained important skills, as well as learning about the Australian way of life. Anecdotes abound of students who studied in Australia ascending to positions of power and influence in their home country: Indonesia’s Minister of Finance and Minister of Foreign Affairs; the Solomon Islands Prime Minister; the Permanent Secretary of Health in Mozambique.

Beyond individual advantage, research also suggests that there are broader societal benefits that may result from scholarships, including advancing economic productivity, and the promotion of democracy and human rights.

Scholarships to study in Australia are a potential tool to express “soft power” [pdf], perhaps through personal affinity or through a developed understanding of Australian thinking and action. Fostering links has become a core objective of the Australian scholarship program and the Foreign Minister has explicitly asserted that the outgoing scholarships for young Australians heading to Asian universities are part of a soft power strategy.

A first critique of scholarships centres on breadth of impact and cost-effectiveness. Focusing on in-Australia study, a 2011 Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report [pdf] stated that “there is good evidence that this (funding for in-Australia tertiary scholarships) is at the expense of more cost-effective in-country and in-region training … which yield much higher development returns.”

One scholarship can cost the aid program more than $100,000: two years of masters level study plus living allowances. And the cost of managing scholarship schemes is very high. In the African context for example, for both masters awards (242 in 2014) and short-course awards (more than 450 in 2014), DFAT staff and managing contractors have had to engage with government departments in more than 40 countries, sift through more than 7,000 applications, organise applicant interviews, and then arrange travel, visas and logistics for about 700 successful applicants. An early iteration of the managing contractor human resources plan for African scholarships had 59 team members.

Furthermore, the link between scholarships and poverty reduction can be questioned, noting that scholarships do not generally target the poor and only directly impact a relatively small number of people. Indeed, stories of children of government ministers securing scholarships continue to circulate.

A second critique is that some of the biggest beneficiaries of the scholarship program are Australian universities who capture substantial portions of the aid funding in the form of fees. Universities, such as my own University of Sydney, welcome a good number of aid scholarship recipients each year, paying full international student fees. An additional component of their scholarship goes to property renters. In this way, much of the aid dollar remains in Australia. Given that masters and PhD scholarships are almost exclusively reserved for those studying at Australian universities, this represents a form of tied aid.

Lastly, as noted in a 2011 post on this blog and in a similar post from 2013 on Crikey, the scholarship program has “struggled to prove its effectiveness, with little evidence of its impact beyond anecdotal evidence of individual success stories.”

There are few publicly available, independent reviews of scholarship outcomes. The ODE has not released any work on scholarships via their website. According to an ANAO report from 2011, since 2005 the Australian government conducted 25 reviews and evaluations of the scholarship program but none have been made publicly available. Since then, an evaluation of Australian scholarships in Cambodia has become available [pdf] as has a summary [pdf] for Pakistan. However, peer-reviewed literature on scholarship outcomes continues to be limited.

While the monitoring and evaluation of the scholarship program has been strengthened over recent years, evaluating scholarships is very tricky. Long time frames are needed to assess full impact and the counter-factual of what the individual would have done without the scholarship is impossible to assess.

These are big, important questions for the aid program. Most would agree that scholarships have a role to play in an Australian aid program but questions of effectiveness, delivery models, recruitment procedures, fairness and value for money are all fair veins of examination by those interested in our aid policy. With that in mind, the second part of this series will examine some emerging results from research that we have conducted among Australian scholarship alumni in three African countries.

This is the first in a three part series on the effectiveness of scholarships in the Australian aid program, collected here.

Joel Negin is a Senior Lecturer in International Public Health at the University of Sydney.

$100K seems a little low if including all the direct costs? Sad to say in my own quite extensive experience in PNG, most recipients return and then request further study opportunities. There is also a big problem in selection with those in the know accessing the opportunities not always on merit – esp. within the public service recommendations.

Appropriateness of education & training is also an issue with dentists etc. trained with equipment and methods they do not have access to in their own context.

Another cost is to the department they leave behind. I have worked in three key departments where the one leading light in each in terms of a very skilled, upwardly mobile professional “doer” … doing great things, was whisked away to study, never to be seen in the department again. Effectively kneecapping the initiatives in train by taking away one of the very few effective people.

Talking to many scholarship awardees after they return to PNG, they generally describe feelings of depression and stress after being home for a while. Perhaps blessed with more technical skills and knowledge but back in the same environment where they began – i.e. no power, no medicine, poor management and leadership.

You would think in these days of technology, if scholarships are to continue many courses (especially Masters) could at least be partly completed in an external mode with more bang for buck, less disruption to families and workplaces and more skin in the game for the participant who would have to demonstrate their capacity and desire to learn.

Hi Joel

This is quite an interesting topic, thanks for writing about it. I would definitely agree – “the link between scholarships and poverty reduction can be questioned” (despite thinking that scholarships are a really valuable part of the aid program). The scholarship itself and the individual it targets might not be an example of a poverty reduction activity. In my opinion, it’s what the person goes on to do afterwards and the choices they make that create development outcomes. The action the person takes over the next twenty or thirty years in their career (as a result of learning on-scholarship) would foreseeably impact on poverty reduction in their home country.

The scholarship can become the means for the individual to make greater contributions and add more significant value during their career/lifetime. That’s one reason why effective awardee selection processes are so important. The masters/PhD program is not the catalyst for change, it’s the individual that creates the change. Donors need to make sure the right people are selected for their scholarships, in order for the scholarship program to hold value. Scholarships don’t necessarily need to go to the poorest of the poor, rather to individuals with great potential.

The Australia Awards alumni network would be capturing some good stories of the short term impact of scholarships – it would be interesting to hear some of these.

Cheers

Jen

Thanks Joel for this post and I genuinely look forward to the follow-on posts.

This is a topic that has been of great interest to me for many years through my own studies (evaluating scholarships worth, though probably not as well as you are), as well as being involved in the management of some aspects of the scholarships program/s.

I still think there is more reimagining necessary.

I do believe scholarships (in whatever form) can play an important role across an aid/trade/diplomacy spectrum. However, there is still the potential for some aspects of a scholarship program (when funded by an aid program) to resemble a full fee international student through a different marketing channel.

In the context of the new Australian aid policy, renewed vigour for the of the role of the private sector, and for the concept of innovation, challenging status quo seems worthy of consideration…unless of course your subsequent posts signal status quo perfection…

Although I may be biased, having completed a Masters by research on this exact topic, I think it is incredibly important. In my experience, scholarships were viewed by aid researchers, academics and many practitioners as outside of the scope of aid, and thus not worthy of a their attention. They have in many ways fallen through the cracks between aid and diplomacy.

Whether we like it or not, they are part of Australia’s aid budget so any attention is warranted and I would argue, absolutely necessary.