On Tuesday, March 20, Devpolicy hosted a forum to discuss how Australia can best engage in global health R&D (details here, video of the forum here).

The starting point for the forum was the 23rd recommendation of the 2011 Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness, namely that “There should be more aid funding for research by Australian and international institutions, particularly in agriculture and medicine.”

The Government has agreed to this recommendation, and the main focus on the forum was on how to implement it. However, one of the most striking stories from the forum had more to do with the why. Mary Moran, Executive Director of Policy Cures, highlighted (see her slides here) the amazing impact a recent Meningitis Vaccine is currently having across Africa.

MenAfriVacTM Meningitis A

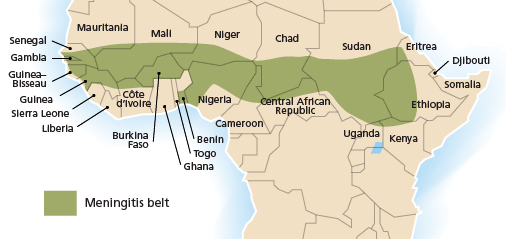

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges, the thin lining that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Bacterial meningitis has a rapid onset and brings with it significant risk of death and disability. Meningitis A remains particularly acute in the sub-Saharan beltway of Africa, with an at risk population of around 430 million. Over one million cases of meningitis, often occurring in epidemics, have been reported in Africa since 1988.

The African Meningitis Belt.

Until recently, the main method of combating meningitis was through reactive vaccination campaigns. A reactive campaign is where officials respond to ‘early’ detection of epidemics with emergency mass vaccinations with vaccines that are expensive and short-acting, meaning they have less of an effect preventing future epidemics in Africa. These campaigns have been massive, expensive and disruptive. They have also had little to no public health impact because they are often rolled out too late.

The Meningitis Vaccine Project (MVP), a joint project between the WHO and PATH in 2001, primarily funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, was established with the sole task of developing a meningococcal vaccine specifically for sub-Saharan Africa in order to eliminate this disease as a public health problem for the region.

This new form of R&D investment strategy, known as a Product Development Partnership (PDP), allowed MVP to ‘partner with the best’ in the private sector to develop, test, introduce and widely distribute a vaccine. Ten years later MenAfriVacTM was licensed. The numbers from the initial three-country rollout, summarized below, are remarkable. In Burkina Faso, the number of reported infections has fallen from 6, 145 in 2010 to 2, 824 in 2011. No-one vaccinated has been infected.

The decline in meningitis infections in the three West African pilot countries

From Mary Moran’s presentation, based on WHO disease surveillance data for the first six months of each year (see here).

From Mary Moran’s presentation, based on WHO disease surveillance data for the first six months of each year (see here).

This truly is a game-changer. Over the next decade, through an integrated rollout in all 25 countries in the African belt, the program is projected to prevent over 400,000 cases of meningitis, save 44,000 lives, and avert 105,000 disabilities. High coverage of the 315 million-target population, aged 1-29 years, is expected to eliminate epidemics from this region of Africa.

A single vaccine costs only 40 cents to produce, half the cost of the less effective vaccines currently available. The MVP has forecast total costs to be about US$475 million to cover the targeted population over a ten-year period, with costs shared between donors and partner governments’ health budgets. To date, the cost of discovery of the MenAfriVacTM vaccine has so far been $87 million, less than one-tenth [pdf] the US$500 million cost typical of bringing a new vaccine to market. An extra $29 million has been provided by the GAVI alliance to finance the pilot programs.

Health R&D and fragile states

A common response to the suggestion that Australia ought to invest more heavily in global health R&D is that our focus is, rightly, on getting existing drugs to market. It is often suggested that this is enough of a challenge, particularly in fragile states where Australia predominantly works. But in many cases there is no existing drug or vaccine to bring to market: it needs to be created or patients will die, as was the case with meningitis.

Another striking aspect of the West Africa meningitis case is that the countries involved are fragile states. Niger is ranked 15th on the Foreign Policy index of failed states, and Burkina Faso 37th, both above PNG at 54th. Mali is ranked better at 77th, but has just experienced a coup.

As the meningitis story shows, new vaccines can make a difference even in fragile state environments. Australia’s focus on fragile states should not be a reason for doing less on global health R&D. To the contrary, investing in global health R&D should be seen as a way to increase the return on the heavy investments we are making in health care in our neighbouring countries.

Jonathan Pryke is a Researcher at the Development Policy Centre.

Leave a Comment