Aid advisers in Papua New Guinea: a full solution

By Joachim Luma, Michael Anderson and Carmen Voigt-Graf

24 April 2017

The 2016 PNG Regulation covering non-citizen technical advisers (discussed in our earlier post on the subject) seems to have primarily resulted from a desire within the PNG Government to exert its national sovereignty. Under it, foreign government employees can only be engaged on a short-term basis under an Institutional Partnership Arrangement. PNG’s sovereignty has also been enhanced by the new requirement that the Agency Secretary give final approval for the engagement of a non-citizen technical adviser and sign a performance contract with that adviser. The requirement that the Secretary of PNG’s Department of Personnel Management keep a register of all non-citizen technical advisers also reflects PNG’s desire to increase its control over the engagement of non-citizens in its public service.

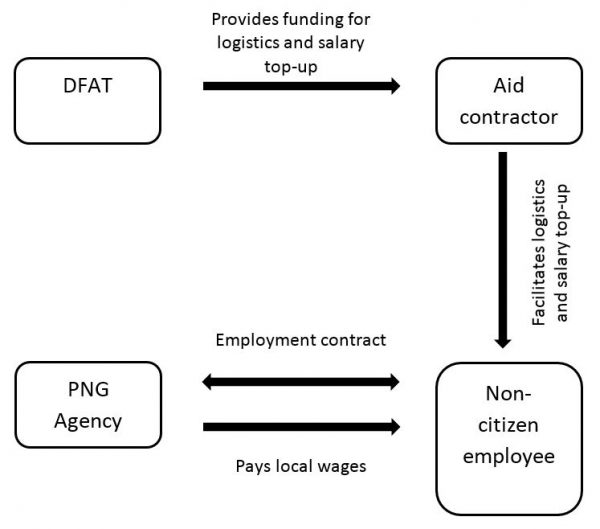

PNG and its development partners should consider further reform in this space. We hold the view that non-citizen technical advisers who are embedded in the PNG public service should be employed by the PNG Government, not by a contractor. In this scenario, aid contractors would coordinate the logistics but not act as the employer of these advisers (see Figure 1). The benefits of this approach are greater accountability and greater scope for aid funded non-citizens to be engaged in in-line positions and not just as advisers.

This proposed model is consistent with the Joint Review of Technical Adviser Positions in 2010 that recommended greater use of in-line officers that are contracted directly to the PNG Government who have full delegations of public servants, are accountable to the PNG Government and undertake the full functions of the role with the additional component of capacity building.

Figure 1: Proposed model for engagement of aid-funded non-citizens

The fundamental difference between this proposed model and the currently existing non-citizen technical adviser model is the recognition that the PNG Agency is the employer of the non-citizen. In our view, this reflects the reality of the engagement of many non-citizen technical advisers on the ground in PNG. It makes little sense to have an adviser, who works on a daily basis in a PNG Agency and reports to the PNG Agency Head, to be employed by a commercial aid contractor. As indicated above, this mode is compatible with and will promote the use of the engagement of non-citizen advisers in in-line roles.

PNG already engages many non-citizens in-line under the Public Employment (Non-Citizens) Act 1978. In these instances, the PNG Government is the employer of the non-citizens and is responsible for all costs associated with the adviser.

A model for co-funded positions also already exists in PNG with the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Fellowship Scheme. The PNG Government can make a request to ODI for staff with specific economic skills. ODI Fellows work as local civil servants for a period of two years, with the cost being shared between the PNG Government and ODI. Under the ODI model, the PNG Government as the employer is responsible for paying a salary equivalent to what would be payable to a locally recruited national with similar qualification and experience; providing conditions of service such as accommodation and leave entitlements similar to those offered to local staff in similar grades; and ensuring fellows receive assistance in obtaining work permits and security clearances where required. ODI on the other hand is responsible for selecting fellows, arranging placements; providing a pre-departure briefing and allowances; paying a monthly supplement; providing medical insurance; and paying an end-of-fellowship bonus.

Under the ODI model non-citizens are employed by the PNG Government and work in in-line positions, allowing them to make decisions and supervise staff, without the PNG Government having to bear the full costs. Non-citizens are employed in approved, funded, vacant, established positions and are subject to the same public service laws and standards as their PNG colleagues. By incorporating them into the establishment and by paying them their base salaries, the PNG agencies take ownership of their non-citizen employees. Non-citizens occupying in-line positions cannot be referred to as advisers but can be called non-citizen employees.

ODI Fellows represent a very small component of the adviser program in PNG – there are currently only four ODI Fellows working for PNG Agencies. But the ODI model could and should be used and adopted by other donors including DFAT. The role of aid contractors would be restricted to arranging the logistics (accommodation, health insurance, transport and security), and the payment of salary top-ups. DFAT would continue to be the source of the majority of the funding. The top-up of salary and payment for logistics by DFAT reflects the reality that this is necessary to both attract and retain non-citizen employees.

The adoption of a new model for non-citizen technical advisers (or employees) would need to be supported by legislative and regulatory reform. At the very least, PNG will have to review and update the Public Employment (Non-Citizens) Act 1978 which has remained largely unchanged since it was brought into operation shortly after independence. Similarly, the PNG Public Service General Orders do not provide adequate guidelines for the in-line engagement of non-citizens, particularly as they relate to advisers who are co-funded by contractors as part of an aid program. Lastly, there are a range of other matters (including important taxation issues) which will require careful consideration by both PNG and Australia before a new model for advisers can be introduced. But all of these obstacles can be overcome; all that is required is commitment from both parties to embrace a new way to engage non-citizens in PNG Government Agencies.

Joachim Luma is the Manager Executive and Legislative Reform Branch with the Department of Personnel Management during the development of the new Regulation. Michael Anderson was a non-citizen technical adviser to the Department of Personnel Management during the development of the new Regulation. Carmen Voigt-Graf is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

This is the second post in a two-part series; read the first post here. Both posts are based on an Issues Paper recently released at the PNG National Research Institute.

About the author/s

Joachim Luma

Joachim Luma is a graduate of the University of PNG and PNGIPA. He currently works for DPM in the Legislation and Administrative Reforms Division and was involved in developing the non-citizen technical adviser law. His home village is Mai in West New Britain Province.

Michael Anderson

Michael Anderson worked as a non-citizen technical adviser within the Department of Personnel Management during 2016. He assisted the PNG government develop and implement the new Regulation for non-citizen advisers. Michael has previously assisted a number of PNG agencies with employment-related matters.

Carmen Voigt-Graf

Carmen Voigt-Graf was a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre from 2014 to 2017 as well as a Senior Fellow at Papua New Guinea’s National Research Institute.