Aid in fragile and conflict-affected states

By John Eyers

27 February 2012

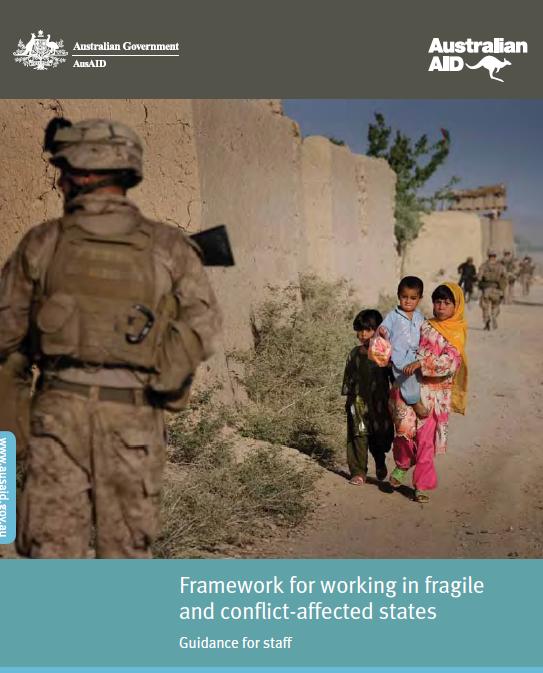

AusAID has recently posted on its website a paper of around 100 pages titled Framework for working in fragile and conflict-affected states: Guidance for staff.

This is of interest not only within AusAID, but also to stakeholders who want to understand how the design and implementation of Australian aid are adapted to these countries’ situations. Many of the countries in the Asia-Pacific region to which Australia contributes aid are fragile or conflict‑affected. Others contain conflict‑affected regions, such as Mindanao in the Philippines. In recent years more than half by volume of Australia’s bilateral aid has been provided to fragile or conflict-affected countries, and this may well continue for some time.

The paper draws on a growing literature about how best to provide international aid in situations of fragility or conflict. This includes principles formulated in 2007 by the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD and the World Bank’s study of conflict, security and development in World Development Report 2011. The paper also draws on AusAID’s experience, and that of other Australian agencies involved with it since East Timor in 1999, in “whole of government” interventions which combine development aid with security assistance.

Readers will find in the paper an informative description of what characterises fragile and conflict‑affected countries, and of what should be done – or attempted – in Australian aid programs to accommodate or remedy these characteristics.

Part 3 of the paper is about how AusAID operates in fragile and conflict-affected states. Some of this is about AusAID’s internal processes, such as advocating careful analysis of local conditions, or the continuity and training of staff. As for the form of aid operations, the main ideas in the paper are:

- support only a limited number of large-scale programs;

- where conflict in a region (eg Mindanao) reflects deficiencies in the national political settlement, work at both levels;

- choose to associate or dissociate service delivery with state structures according to the quality or trend of governance … (later) work as much as possible through partner governments, but where necessary help to develop non‑state organisations; and

- avoid harm, notably through taking sides in internal conflicts or undermining local capacity.

Understandably, there’s not much in this that’s new, even compared with AusAID‘s publications on the same issues under the previous government – only the thoroughness of the exposition, and some matters of emphasis and detail. Indeed, for many readers these operational principles may seem fairly obvious. But the paper tries to bring them to life through illustrations in text boxes describing recent Australian programs in particular countries.

Presenting things in this way – a long exposition in general terms, with success-story boxes – has several implications. First, it underplays the conflicts of objectives – most evidently, between wishing to improve the functioning of government institutions in fragile states and wishing not to be associated with their corruption or their role in internal conflicts. And secondly, it makes the overall message resolutely positive, suggesting things can always be done to help in these situations – even while acknowledging that determining what to do is unusually difficult, there are more than the usual obstacles to aid effectiveness, and progress is likely to take a long time.

AusAID’s wish to present a positive story is legitimate, but at some points the paper’s allusions to challenges are blandly optimistic – for example, in the section on pages 75‑6 about working with external partners, where it suggests that “AusAID can help governments build the capacity to coordinate others”, commends the brokering role of the UN system, and observes that when large multinational companies want to exploit natural resources, “governments need to ensure appropriate checks and balances are in place”.

In that section, and more broadly, readers may find in the paper a different underlying message: that there are situations in which for reasons of security or foreign relations Australia must provide aid, even though making this aid effective is at best improbable and at times impossible.

John Eyers is a former official of the Australian Treasury.

About the author/s

John Eyers

John Eyers has worked in the Australian Treasury, the Asian Development Bank, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the Office of National Assessments, the Papua New Guinea Treasury, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.