Fessehaie Abraham: the refugee who brought Eritrea to Australia

By Stephen Howes

In October 1989, Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke launched Thomas Keneally’s new novel, Towards Asmara, at Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks. Wedged between Hawke’s launch and Keneally’s response are some short remarks by one Fessehaie Abraham, who just a decade earlier had arrived in Australia as a refugee. How did a recently-arrived refugee come to stand shoulder to shoulder with Australia’s most popular Prime Minster and its most popular novelist? This essay makes a start in telling Fessehaie’s story.

Towards Australia

Fessehaie Abraham was born in Eritrea, a small country on the northern coast of the Horn of Africa, with a population of about five million. His parents were farmers. He was the first in the family to go to school. Eritrea had been under Italian and then British rule, but, as part of the post-colonial settlement, it had been federated with Ethiopia in 1952, the year of Fessehaie’s birth. The union was never a happy one, and a war between the Eritreans and the Ethiopian government broke out in the early 1960s, and intensified in the 1970s.

In 1970, Fessehaie went to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, to study chemistry. With escalating conflict, the university was closed in 1974 and he was forced to abandon his studies. At first, he worked as an aid volunteer in Addis. Return to Eritrea via Ethiopia was impossible due to the conflict. In 1976, Fessehaie ventured to Somalia to make his way to Eritrea via sea to join the liberation struggle, but the boat he was waiting for never arrived. He then went to Kenya, where he was detained for being an illegal migrant. In 1977, Sudan accepted him as a refugee. A friend of a friend from his aid volunteer days was back in Australia and agreed to sponsor Fessehaie as a refugee. He arrived in 1978, as Australia’s first Eritrean refugee.

In 1979, Fessehaie enrolled at the University of New South Wales to study chemical engineering. His one aim was to get an education. His other was to support his people and their struggle. At the time, there were only a handful of Eritreans in Australia. Fessehaie started work on establishing the Eritrean Relief Association, or ERA.

Eritrean Relief Association

For the next 15 years, the ERA mobilised Australian support for Eritrea, raising millions in relief and development assistance, and making the tiny, faraway nation an important foreign policy and aid concern for Australia. For all that period, Fessehaie was the ERA Coordinator, first part-time while he was studying and then, for more than a decade, full-time.

His first breakthrough came not long after he arrived. In 1980, he had a medical appointment.

“Like many Eritreans, I had trachoma. I went to see this eye specialist called Fred Hollows. While he was examining me, he asked me where I was from and what I was doing. So I told him.”

Fessehaie always carried an ERA pamphlet setting out the Eritrean cause and gave one to Hollows.

It wasn’t till 1987 that Hollows actually got to visit Eritrea (in a visit organised by Fessehaie), but the effects were profound. He was impressed by what he saw, both by the dignity of the people and by their efforts to provide medical care in a situation of war. In 1990, despite having received a cancer diagnosis, Hollows, accompanied by 60 Minutes, made a second trip, and conceived of the idea that a factory to make the intra-ocular lenses required for cataract operations should be built in Eritrea. He calculated that it would cut the cost of the lenses from $150 to only $2 each. Hollows dedicated himself to the factory’s construction, and started fundraising back in Australia. The Australian government lent its support. The equipment was manufactured in Australia, and shipped to Eritrea. It was opened in 1994, the year after Hollows died, by then Foreign Minister Gareth Evans.

There was growing concern in the early 1980s with famine in the Horn of Africa. Fessehaie and his colleagues persuaded the Australian government that support given to the Ethiopian government would not help those in Eritrea because of the war. An early supporter was Labor Senator Kerry Sibraa, who had a life-long interest in Africa and went on to chair the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade, and later become President of the Senate. Sibraa participated in two parliamentary inquiries into the Horn of Africa. One, in 1983, on The Provision of Development Assistance and Humanitarian Aid to the Horn of Africa, recommended that, because of the ongoing war, aid to Eritrea be delivered not through the Ethiopian Government but through the Eritrean Relief Association and the Australian NGOs associated with it. Given that at the time Eritrea was part of Ethiopia, this was a bold recommendation – and a vindication of Fessehaie’s and ERA’s lobbying efforts.

In 1984, the Australian government approved the first request from ERA for emergency relief. In 1985, four Australian NGOs came together to form the Food Aid Working Group to work together with ERA to manage emergency aid to Eritrea.

By the mid-1980s, the famine in the Horn of Africa had become front-page news. Thomas Keneally became interested, and wanted to find out more. Kerry Sibraa put him in touch with Fessehaie, whom Keneally later described as a “genial and persuasive fellow [who] offered to arrange a research visit for me, if I were willing to go.” Keneally’s novel, based on his trip to the Eritrean front line, is credited with helping to bring the Eritrean cause to international attention. One review even reckons it helped to bring about peace negotiations.

Indeed, Fessehaie’s converts to the Eritrean cause were legion. Apart from the ones already mentioned, they include a who’s-who of the Australian NGO world: Mike Toole, Patrick Kilby, and three who went on to head the peak body ACFID: Russell Rollason, Fessehaie’s first contact, Janet Hunt and Graham Tupper. Fessehaie also got a stream of journalists and media crews to Eritrea, and facilitated visits from The Age, Sunday Mail, ABC and Channels 9 and 10. He befriended numerous politicians on both sides of politics, including former Liberal Ministers Richard Alston and Robert Hill, and Labor ministers Bob McMullan and Chris Schacht. Tim Fischer, former leader of the National Party and Deputy Prime Minister, wrote Fessehaie into Hansard with the parliamentary observation that “he has been a very dedicated representative of the people of Eritrea.”

Fessehaie himself, however, talks modestly about his own role.

“It was never me who captured the imagination of people such as Fred Hollows and Tom Keneally. It was my country and my people. All I did was to confront people with the human face of what was happening and they saw and understood the injustice.”

Liberation

The war finally came to an end in 1991. The tyrannical Mengistu regime, which had governed Ethiopia from 1974, was weakened by the fall of the Soviet Union, and a loss of Russian support. In 1991, it was overthrown by the Eritreans and other disgruntled groups, notably the Tigrayans. The new Ethiopian government agreed that Eritrea should hold a referendum on independence. This was duly held in 1993, and showed overwhelming support. Independence was declared that same year.

In what seemed to be a seamless transition, in Australia the Eritrean Relief Association was disbanded in 1993. What need was there now for a non-government body to represent the people of Eritrea to Australia, when there was now a legitimate government to do the job?

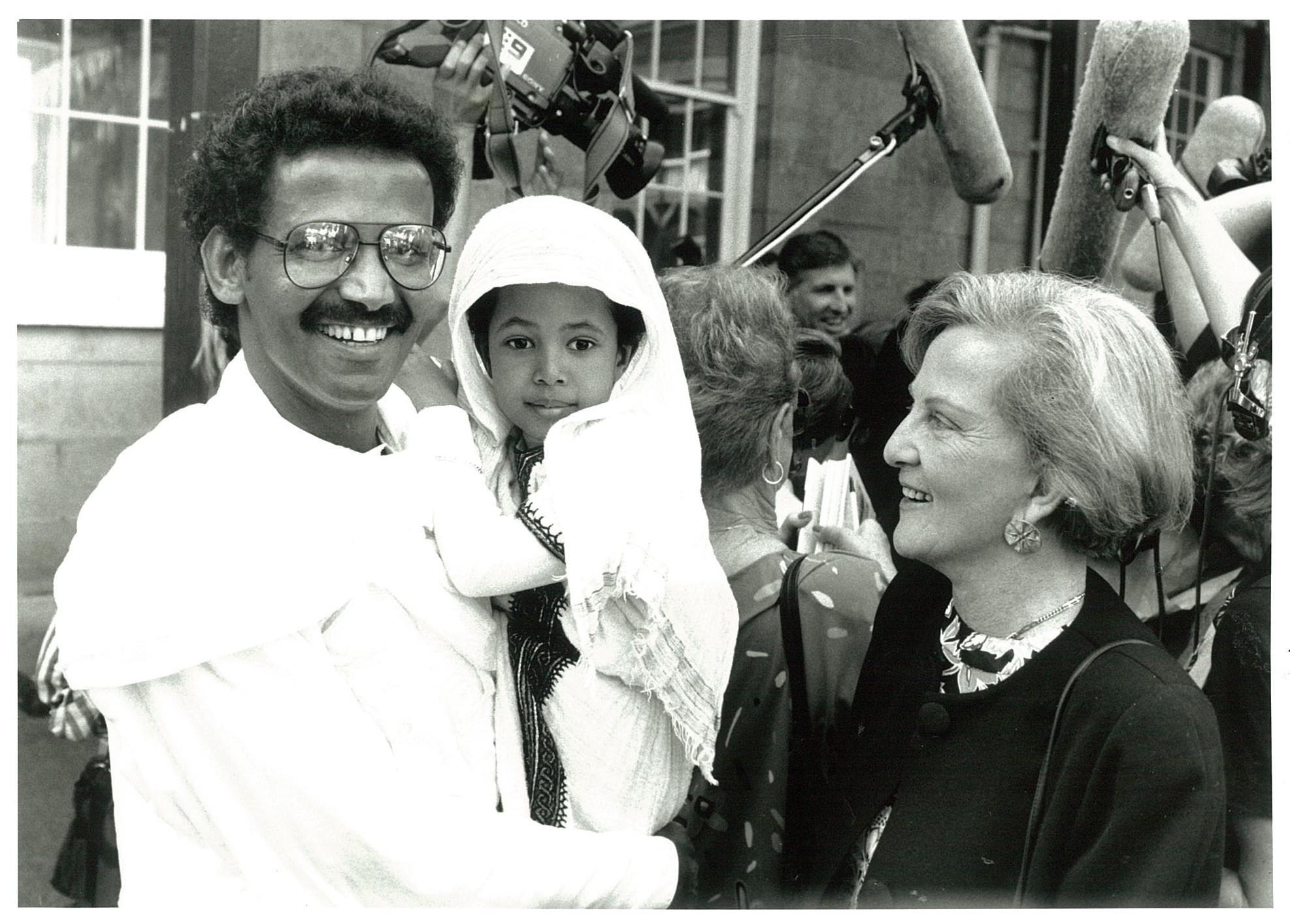

Official links between the two countries had grown as a result of Fessehaie’s efforts. Even before independence, in 1989, Australia had hosted a quasi-official visit from the Eritrean rebel leader Issaias Afewerki.

Eritrea decided to deepen these links by appointing Fessehaie as Eritrea’s first Ambassador to Australia. In 1993 he opened Eritrea’s embassy in Canberra, one of its first outside of Europe, and itself a remarkable achievement – and statement of optimism – given the country’s small size and distance from Australia.

Australia’s support to Eritrea intensified. The University of New South Wales, Fessehaie’s alma mater, commenced a twinning program in engineering with the University of Asmara. Several Australian parliamentarians visited Eritrea, including four to observe the 1993 referendum. In 1994, on his visit to open Fred Hollows’ factory, Foreign Minister Gareth Evans signed an MOU with the new government of Eritrea. Australian aid to Eritrea increased to $6.5 million per year. An Australian dental team visited. Twenty Eritreans came to Australia on scholarships. Thirty Australians went to Eritrea to work as volunteers. There was interest by Australian mining companies in Eritrea’s mineral prospects, and two exploration leases were signed.

The long decline

The independence referendum turned out to be the first and last election ever held in Eritrea. A constitution was ratified in 1996, but it has never been implemented. In 1998, a border dispute with Ethiopia arose. It ended in 2000, and UN peacekeepers were brought in. UN demarcation of the border was agreed to, but only Eritrea, not Ethiopia, accepted the UN’s ruling. Since then the two countries have been in a state of hostility, and at times outright war.

Eritrea, once the beneficiary of international aid and goodwill, is now the subject of United Nations sanctions, imposed in 2009 on the basis of disputed accusations that the Eritrean government aided terrorists in Somalia.

In the meantime, the former leader of the armed struggle and current president, Issaias Afewerki, moved to solidify his control. One by one, his former colleagues disappeared into jail or took themselves into exile.

Today, it is literally one man rules. Issaias Afewerki heads one of the most oppressive governments in the world. It receives the lowest score possible from Freedom House in respect to both political and civil rights. Reporters Without Borders has ranked Eritrea as having the least freedom of expression in the world.

Nor has the sacrifice of liberty been in the pursuit of economic development. Eritrea is reported to have the second highest rate of child stunting in the world. Eritrea comes 189 out of 190 countries on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index. Conscription for virtually a lifetime of army service fuels a massive outward exodus. The World Bank estimates that about 20 per cent of the population has left.

Fessehaie himself didn’t last long as ambassador. After a couple of years of service, he was asked by his government to relinquish his Australian citizenship if he wanted to continue. He refused, and his term came to an end in 1997.

Alienated from his homeland, Fessehaie once again had to invent a new life for himself and find a job to support his family. He did an MBA, worked as a consultant, and then in 2003, joined the Australian government, ending up in Finance, where he worked until his retirement a few months ago.

Eritrean man

Eritrea’s recent history seems straight out of Animal Farm. Anderbrhan Welde Giorgis is one of the several former senior leaders of Eritrea now in exile. He writes in his recent book Eritrea at the Crossroads that “the struggle waged to liberate Eritrea from foreign oppression has ended up installing a regime that perpetrates even more brutal repression.”

No one could have predicted the extent of Eritrea’s recent demise. But its fall from grace is made all the more appalling by the high expectations attached to the country at the time of independence. Valerie Browning — the famous Australian nurse still living in the Horn of Africa, and another Fessehaie supporter — talks in her autobiography of the West’s “love affair” with Eritrea. During the Eritrean war, the admiration of Westerners for Eritreans went well beyond an acknowledgement of their bravery, determination and skills. It was almost as if a new type of man had been discovered: Eritrean replaced Soviet man.

Fred Hollows in his autobiography titles one of his chapters “The Amazing Eritreans”. Written in 1991, just as the war was ending, Hollows explicitly addresses those who are pessimistic about what peace might bring to Eritrea, and explains why he is “so optimistic about the prospects for Eritrea now that the war is over.” Peace will bring challenges, he accepts, but he has faith “because the people have fought so hard that I very much doubt that the opportunists and self-seekers will get a look in.”

In fact, it was precisely the three decades of war, and the use of force not only against the enemy but internally to obtain and preserve power, that created the conditions within which post-war one-man rule could thrive. As Welde Giorgis writes: “The use of force as an arbiter of discord or as a means to intimidate people to conform has survived the armed struggle and has evolved as a persistent practice of the present governance system.”

Bittersweet

Regardless of whether the Australian supporters of the Eritrean liberation struggle were naïve, their achievements cannot be denied. During the war, they mobilised an estimated $32 million from the public and the Australian government for live-saving relief. And their crowning achievement, the Eritrean factory, survives to this day as Africa’s only intraocular lens factory. It has produced 2.2 million lenses, and, while the sanctions are a challenge, still manages to export them around the world.

There are also broader achievements. Hollows worked overseas in Nepal before going to Eritrea, but his project in Eritrea was his first large one, and first foray into fundraising in Australia. The Fred Hollows Foundation has since become one of the largest Australian development NGOs. At the opening of the Eritrean embassy in 1993, Gabi Hollows, Fred Hollows’ widow, described the Eritrean factory and training as “the highlight of the work that Fred and I have done.”

What does Fessehaie make of it all, when he looks back at his life’s work?

“I see it in two stages. In the first stage, we made a lot of sacrifices, and we achieved independence against all odds. That’s almost unimaginable. An incredible achievement. I’m not just talking about the fighting forces. The ERA had an office in about 13 countries. We mobilised a lot of international support for our people and I believe we had a big impact.

In the second stage, after independence, we started OK, but we have stumbled. We’re now in a situation that makes me sad every day, and makes me wonder what will happen next. But I still haven’t lost hope. This is part of the transition of a revolutionary movement. Somehow, we haven’t struck the formula for a smooth transition to a democratic, people’s government. But I’m still optimistic. The current situation is a passing phase. My only hope is that Eritrea should stay intact. Time has got its own answers.

But what really makes me sad is the opportunity cost. The amount of Australian support we had was incredible. That was disrupted, and I’m looking forward to a time when we can actually revive it.”

And what about at a personal level? How has Fessehaie coped with the relative boredom of a public service job after the decades of heroic struggle? He gives a simple answer:

“I’m happy to be alive. I was lucky not to be martyred in the armed struggle, like most of my classmates. My wife and daughter have helped me maintain my balance. And I’ve learnt a lot from my work about the differences between developed and developing countries. It’s really about governance and the rule of law.”

An extraordinarily effective lobbyist

Fessehaie’s story speaks to the both the value and the limits of aid. That there are sharp and sometimes tragic limits does not negate the enormous value of international assistance.

His story is also an example of the invaluable connecting and brokering role that the diaspora can play in international development. Fred Hollows sums it up well in his autobiography. Fessehaie Abraham was indeed “an extraordinarily effective lobbyist for the Eritrean cause in Australia.”

Stephen Howes is the Director of the Development Policy Centre, ANU.