Sanasa: Sri Lanka’s Grameen Bank, and Australia’s role

By Stephen Howes

This is a story about partnership and friendship achieving great things. Sanasa is a Sri Lankan microfinance success story. Kiri is the person who made it happen. Oxfam Australia provided a crucial role in the organisation’s early growth, thanks to its director of programs, Neil O’Sullivan, and a lot of trust.

Sanasa

There are more than 8,000 Sanasa societies – local microfinance cooperatives – spread over Sri Lanka’s villages with about one million members. The societies together with their peak bank and insurance agency have assets of more than one billion Australian dollars.

The village cooperatives are autonomous bodies, each separately registered with the Sri Lankan government. I recently visited one a few hours out of Sri Lanka’s capital, Colombo. Alawwaththa’s Sanasa society was started in 1979, in the house of one its members. Today it has 600 members and a staff of six. It operates out of a new building, its fourth, which it moved into in 2018.

Each Sanasa society is a local bank, and much more besides. As well as receiving deposits and lending money, the local Sanasa in Alawwaththa also runs educational, housing and insurance programs, as well as a post office. Sanasa seeks to build social as well as financial capital. Its ultimate aim is to empower Sri Lankans through the propagation of cooperative principles.

The 8,000 local Sanasa societies are combined, via democratic elections, into 29 district unions, and then into the nationwide Sanasa federation. These larger bodies represent and support the local societies, through training, instruction and mass-meetings. They turn what would otherwise be isolated societies, prone to decline and decay, into a vibrant, national movement. But. Importantly, the village societies retain their autonomy. They are controlled neither by the national federation nor the district unions. Each local society is separately registered with government, and each one is controlled by its members. Sanasa is an example par excellence of organic, bottom-up, democratic development.

District union meetings are impressive affairs, with attendance in the hundreds. Meetings of the national federation attract more than 100,000. The national federation has spawned over a dozen Sanasa companies. The big ones are a bank (award-winning; with close to 100 branches and 1,400 employees), an insurance agency (a pioneer in micro-insurance), a training-centre-cum-university, and a construction company.

The Sanasa movement emphasises inclusion, and studies have found that the poor are well-represented in the ranks of Sanasa membership. So too are women. Though the leadership is still predominantly male, there is a strong emphasis on gender equity, including several thousand women’s committees, and a number of measures to boost the role of women.

An early study of Sanasa published in 1996 and written by three academics, David Hulme, Richard Montgomery and Debapriya Bhattacharya, described it as a genuine and sustainable “grassroots movement.” The authors concluded that “its achievements stand in marked contrast to its competitors in the Sri Lankan countryside” and ascribed its success “to institutional financial viability; to making services attractive to borrowers and savers; to effective internal management; and to the effective management of external relationships.”

A book on Sanasa was published in 1999 by a Sanasa partner, the Canadian Cooperative Association. Ingrid Fischer and her co-authors compared Sanasa to the much better-known and Nobel-prize winning Grameen Bank of Bangladesh:

The Sanasa movement represents one of the best examples of how cooperative development through micro-finance can work—rivaling other, better publicised approaches, such as Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank—to finance economic development.

Sanasa’s success has been against the odds. Back to David Hulme and his co-authors:

When set against the comparative performance of other rural finance institutions and a background of civil war, insurgency and political decay, Sanasa’s performance is remarkable.

The Canadian study is more direct about the adverse environment which had to be endured: “Sanasa members and leaders were murdered in significant numbers in the late 1980s and early 1990s.”

In 2007, the World Bank took a look at Sanasa. Its 2007 report by Graham Owen described it as “a remarkable turn-around story.”

The person responsible for that turnaround is Dr P.A. Kiriwandanaya, or Kiri for short.

Kiri

Sanasa dates its beginnings as a modern, national movement to 1978, but its origins actually go back much further, to the credit cooperative societies established by Great Britain early in the twentieth century during its colonial rule of Sri Lanka. By the 1970s, however, Sri Lanka’s credit cooperatives had limited and declining reach.

In 1977, Kiri, an activist, set about to change all that. He started in his wife’s village, where, by emphasising inclusion and the need for a more commercial orientation, he transformed what had been “a savings club for old men into a ‘village bank’.” The movement spread. Over the next decade, the number of Sanasa societies increased from 1,400 to 7,600, and the membership from 21,000 to 731,000. In 1978, the first district union was formed. In 1980, the national Sanasa federation was established, with Kiri at its head.

Kiri – a natural leader and an inspirational orator – has remained at the helm of the Sanasa movement ever since.

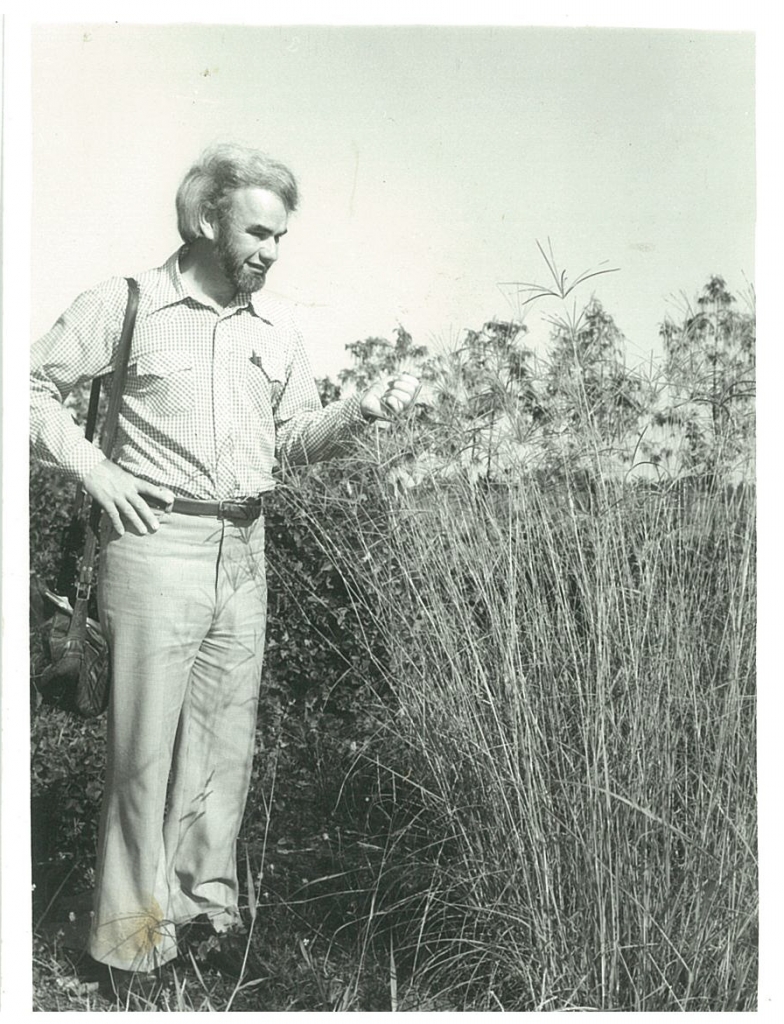

Now in his late seventies, he seems to have lost little, if any, of his energy and commitment. On the few days we had together in late 2018 – a weekend, when he could find time – Kiri drove me around the Sri Lankan countryside, and addressed Sanasa training meetings, a district reunion, and a meeting of founders. I struggled to keep up.

Kiri grew up in rural Sri Lanka, the son of a farmer. His uncle was the village headman, which gave him an intensive introduction to rural dynamics, and his community orientation. At university, he became politically active, but decided against a career in politics, and went down the road of social activism instead. A practicing Buddhist, influenced by both Marx and Gandhi, Kiri settled in his thirties on cooperative ideals as providing a middle way.

His father-in-law was active in one of the earlier credit cooperatives, and this exposure gave Kiri the idea that these groups could provide the basis for a self-help, cooperative movement. Kiri learnt the importance of self-help by bitter experience in his pre-Sanasa days when a politician told local farmers that funds granted by a donor and on-lent to them via Kiri did not need to be repaid. But, for Kiri, it was never just about the money:

The societies were suited to the people’s own (largely Bhuddist) values, and participation in community activities has long been a feature of Sri Lankan culture… From these roots it would be possible to develop a broader cooperative culture.

Kiri is both proud and indeed surprised by what he and the movement have achieved. He says that when he started he had “no idea it would get so big.”

That it did, is due in no small part to the early support Sanasa received from Australia.

Oxfam Australia

Oxfam Australia was begun in 1953, by the redoubtable Father Tucker, who also founded the Brotherhood of St Laurence, now a major Australian welfare agency. Initially called Community Aid Abroad (CAA), the organisation joined the international Oxfam family in 1972, and was renamed as Oxfam Australia in 2005.

Today, the organisation has a budget in the tens of millions of dollars, but for its first two decades, it was much smaller, with no project director and only three field representatives abroad.

In 1977, Oxfam Australia became Sanasa’s first supporter. Its project funding was never in the form of subsidised capital for lending, but to help grow the movement. Kiri remembers colour film – a valuable commodity in the dying days of Sri Lanka’s socialist economic policy regime – as one of the first things that Oxfam provided. In the early days, it helped finance the support for the first several district unions and then for the national federation.

In 1980, Kiri became Oxfam Australia’s fourth field representative. By then, he was head of the newly created national Sanasa federation. It was a full-time responsibility, but he had no-one to pay his salary. Kiri’s job with Oxfam was far from that of a conventional country manager. His job was to grow Sanasa, not Oxfam. This he did, very successfully, on the back of his Oxfam position and ongoing project funding used for pilot activities over the next eight years.

The support was modest – Kiri’s salary, his office and car and some project funding – less than a million Australian dollars over a decade – but critical. Kiri credits Oxfam for being the first to back his vision, and to see the potential of Sanasa as a movement. Prior to that, he says:

No one had given me any assistance. They thought: how can you organise the grassroots? At that time, the Grameen Bank was not there. There was no microfinance market at that time. No one believed that this sort of thing could be implemented.

Which brings us to the man who was prepared to take this leap of faith.

Neil O’Sullivan

An industrial chemist by training and occupation, Neil O’Sullivan became Oxfam Australia’s first project director in 1974, a position he held to 1985. With no prior professional development experience, but a passion for social justice, O’Sullivan was a member of one of Oxfam’s local groups in rural Victoria, and had served on the organisation’s state and national committees. He met Kiri when the latter had a vision to create a national movement but very little by way of track record. It was O’Sullivan’s decision to support him:

When I joined, [Oxfam] was looking at new development theories: liberation theology, the community development approach, empowerment. The program didn’t reflect that at all. I searched around for opportunities and people who might reflect the new thinking. I found a very like-minded character in Kiri.

O’Sullivan explains that the position offered to Kiri was “a fairly simple way of ensuring that he could turn his vision into reality.” Oxfam support was also a means of protection. Today, Kiri is a venerated and decorated figure (with an honorary doctorate and various national awards), but in those days, with his growing popular support, he was viewed as a threat, and was even arrested once.

The relationship between Sanasa and Oxfam was really one between Kiri and O’Sullivan. These two men, both about the same age, both with similar outlooks, became good friends. They still are. Both separately emphasised to me the importance of trust in their relationship. Kiri said that Oxfam respected his independence, which was a condition of his appointment. Although, as field director, he visited Melbourne twice a year, and submitted annual reports and plans, he could not be told what to do. That worked, Kiri said, because “Neil never distrusted me.”

Without me bringing it up, O’Sullivan expanded on the same point:

My initial support for Kiri was based on trust, a conviction that he had the capacity and the orientation that we needed to support. I trusted him. The organisation trusted me. We therefore began to support something where we didn’t know with any real confidence what would happen.

Trust is a personal thing, and it is little surprise that Oxfam’s support for Kiri didn’t much outlive O’Sullivan’s departure from Oxfam in 1985. The fiction that Kiri was actually Oxfam’s field director in Sri Lanka could only be maintained for so long and in 1988, Kiri resigned from that role.

In any case, by the late 1980s the job was done. Sanasa had gained a track record and become well-known. Other donors stepped in to fill the gap left by Oxfam’s departure.

Taking stock

Alawwaththa, the village I visited, now more of a town, is home to a model Sanasa society. They even have a visitors’ book to record the arrivals of development tourists such as myself. There are endless Oxfam Australia visitors, the first in 1984, the last in 1997, Neil O’Sullivan himself, long after he had left the organisation. Some 20 years on from that, what are we to make of the Sanasa-Oxfam story?

Success is never forever or complete, and Sanasa today faces any number of challenges. That of succession is the most obvious. Kiri remains a formidable leader, but an old one. The fact that he has again resumed the position of Chair of the Federation, a position he stood down from a decade earlier, shows the difficulty of letting go.

Samadanie Kiriwandinaya is Kiri’s daughter. She has followed her father into the movement, and is now Chair of the Sanasa Development Bank. I asked her about the succession issue. She disclaims interest in being her father’s successor. Indeed, she says, he is irreplaceable. Instead, the focus has to be on strengthening institutions. “There will be no individual to replace my father, there will be many individuals.”

There are also challenges to the cooperative nature of Sanasa. How long, in an increasingly modernised, networked society, will Sanasa members want to invest in what are, essentially, single-branch banks? And what will the future balance be between the cooperative movement itself, and the commercial entities that the movement has spawned?

Finally, even with the ending of Sri Lanka’s civil war, which raged for most of Sanasa’s existence, there are still political risks facing Sanasa, both from the venality of Sri Lanka’s politicians, and from the country’s ongoing instability: while I was visiting, the country boasted two Prime Ministers.

Indeed, Sanasa is a phenomenon worthy of much more detailed and rigorous study, both historical and evaluative. Essentially, the comprehensive study undertaken by David Hulme and his co-authors in the 1990s needs to be updated: there has been nothing like it since.

But we do not need to wait for that further research to reach the judgement that the growth of Sanasa, its significant financial and social contribution to Sri Lanka’s development, its continued vitality, and Oxfam’s early support should all be remembered and celebrated. Sadly, today that story seems to have been lost in the churn of aid personalities and fashions. Even the website of Oxfam Sri Lanka – a field office still managed by Oxfam Australia – makes no mention of past Oxfam support for Sanasa, even though doubtless that support is the most successful provided by Oxfam in Sri Lanka, and one of the most successful worldwide.

The historical record also requires correction. Practical Visionaries, Susan Blackburn’s 1993 history of Oxfam Australia, has an entire chapter on Sri Lanka, focusing on Sanasa. It is written in an appreciative but somewhat wistful tone, reaching the disappointing conclusion that Oxfam Australia’s strategy in that country, with Sanasa as its centrepiece, was “severely tested … and ultimately found wanting.”

In 1993, the Sri Lankan civil war, which had begun a decade earlier and lasted to 2009, was raging, and this clearly coloured the author’s view. Looking back, however, Blackburn’s assessment seems much too negative. No NGO was ever going to be able to stop, or even influence the course of Sri Lanka’s civil war, which was only ended by a brutal government offensive.

I asked Samadanie, Kiri’s daughter, whether Sanasa had been able to straddle the ethnic divide:

We lost the good cooperative leaders [in the north]. They were challenging the ethnic leaders those days, the Tigers, and they were killed, and then they left the country… On our side, this community never learnt Tamil, as there was no reason really…. My father is loved by the Tamil community. We never had any problem, but we had a lot of disconnection because of the ethnic issues. Now we are rebuilding it. The federation has taken the leadership. The bank has 20 out of its 95 branches in the northern province.

Oxfam Australia’s support for Sanasa deserves to be remembered and celebrated precisely because it is one of the very few international NGO initiatives that have had a national impact – even in a country as divided as Sri Lanka. Certainly for O’Sullivan, Sanasa stands out as unique. Nothing else, he has been involved with, he says:

… would compare with the continual development and progress and success of Sanasa. … It’s been enormously influential in development of rural Sri Lanka. It’s coverage of a country is quite remarkable really.

Sustainability is another thing that makes Sanasa’s story stand out. While a number of donors have followed in Oxfam Australia’s footsteps to provide support to Sanasa, the organisation is unmistakably Sri Lankan. Foreign support today is marginal rather than critical. Again, O’Sullivan, and again the comparison with Grameen:

If you consider the fate of microfinance, despite its tremendous promise, there weren’t a lot of sustainable success stories. Grameen Bank has struggled especially at the political level, and has had massive infusions of external funding. Kiri has had virtually no external support in the form of capital, and it really has been an autonomous, self-perpetuating system, and it’s survived tremendous obstacles, and flourished, kept adapting, and developing new arms and new activities.

And what of Oxfam’s role in all this? How much Kiri and Sanasa were influenced by their association with Oxfam is hard to say. No doubt the projects undertaken and the relationship with O’Sullivan were productive in shaping the inclusiveness of the organisation. But, more fundamentally, would Sanasa have happened without Oxfam?

O’Sullivan, generously, says yes: “Knowing Kiri, he’s unstoppable, he would have found a way.” Kiri, equally generously, says no. He says that Oxfam “is not recognised for the value of their contribution” which provided support when no other donors were prepared to take the gamble.

Without it [Oxfam’s support], I couldn’t do it. I could do it in a limited way, within my capacity, but I couldn’t have developed a national program.

Conclusion

If foreign aid is a lottery, then Sanasa is the jackpot. Yet while this level of impact might be extremely rare, the principles underlying its success have much wider applicability. The Sanasa experience teaches us once again that when it comes to aid for institution building, it needs to be focused, and provided in a flexible and predictable way, over a long period of time.

Sanasa also speaks to the value of trust and friendship, and to risk-taking, both easily undervalued when aid agencies become large and bureaucratised.

Above all, the story of Sanasa speaks to the need to support local organisations and champions. In an era in which we are all – according to the latest development jargon – meant to be “thinking and working politically,” here is an intervention that actually did that. To quote O’Sullivan again: “Kiri walked a very fine line by avoiding political involvement and being very political.”

And which NGOs today would focus their efforts in one country by supporting only one local organisation, let alone for a decade? Localisation might be a familiar cry, but with large country offices, the priority of many NGOs is the next project. The story of Sanasa and Oxfam, Kiri and O’Sullivan, tells of a different way of doing development.