APTC graduates finding it increasingly difficult to find employment

By Richard Curtain and Stephen Howes

17 February 2021

The Australia Pacific Training Coalition (APTC) is a major Australian government foreign aid initiative, commencing in 2008, that has spent over $350 million, and has turned out over 15,000 graduates with Australian qualifications in skilled occupations from carpentry to plumbing, cooking, and personal care.

APTC is to be commended for running annual tracer surveys of its graduates. Would that other long-running aid initiatives so consistently collect vital monitoring data. Between 2011 and 2019, ATPC surveyed 5,975 students, about half of all their graduates, generally within six to twelve months of graduating. Our new Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper uses that data to analyse APTC graduate employment outcomes.

APTC graduates can be divided into two groups – what we call “job-keepers” and “job-seekers”. “Job-keepers” are those students who have an employer to return to. “Job-seekers” are those who don’t have continuing employment – those who need to look for a job after graduating. The number of job-seekers has been growing over time and now makes up 45% of the total number of graduates.

To look at how successful APTC graduates are at finding a job, we need to focus on the 45% of ATPC graduates who are job-seekers. Job-keepers have jobs to return to, so their success rate at “finding” a job is 100%. That is not informative. Hence our analysis focuses on the job-seekers.

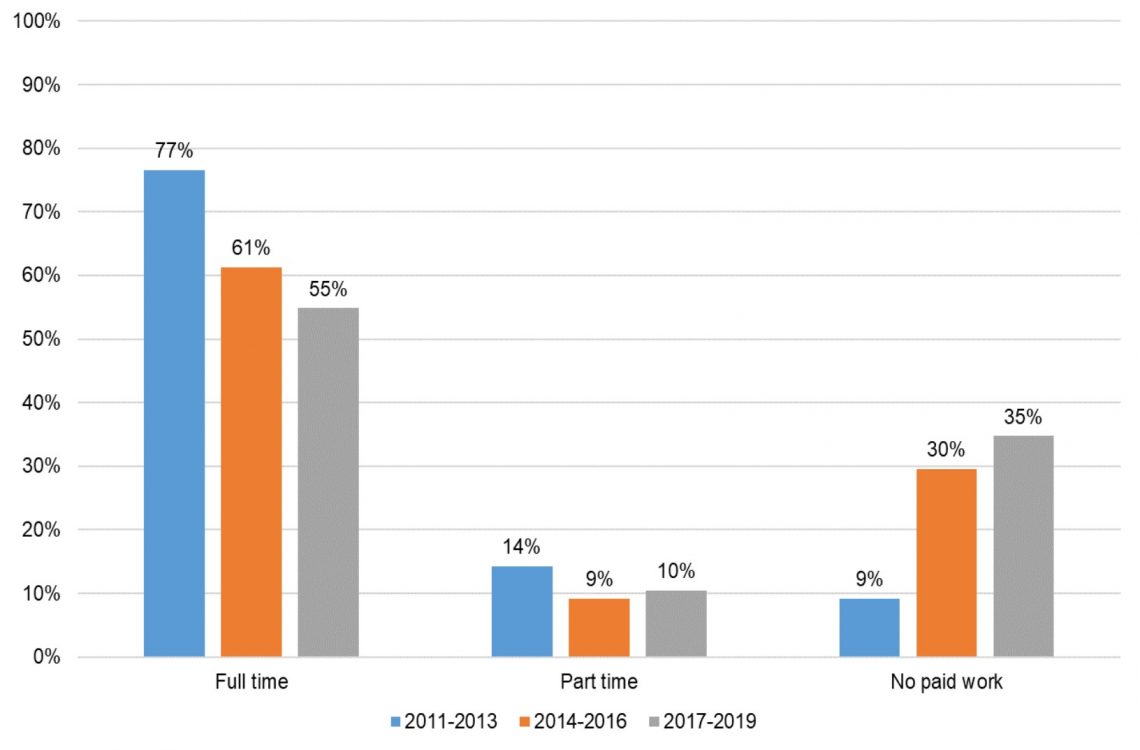

We use three-year averages to reduce volatility. The graph below shows that the proportion of graduates with full-time work at the time of the tracer survey has fallen from 77% in 2011-13 to 55% in 2017-19, and the proportion with no paid work has risen over the same period from 9% to 35%. Of course, some may find work after the tracer survey, but the trends are sharp, and worrying.

Employment outcomes for job-seekers, 2011 to 2019, in three-year averages (%)

We cannot be sure what explains these results. Certainly, they fly in the face of concern about middle-level skills shortages and “brain drain” in the Pacific. The most likely reason, we argue, is that APTC, with its set intakes for long-established courses, has a high risk of oversupplying graduates for the available domestic demand. This is to be expected for Pacific countries which have small wage-based economies. It may even apply to Fiji with its much larger formal economy.

The high levels of unemployment and underemployment for graduates with a range of APTC qualifications suggest that domestic labour markets in the Pacific cannot absorb a continuous flow of post-school technical graduates with the same qualifications.

What is the solution? Clearly, a more demand-led approach to student admission and course selection is needed, as well as a review of the quality of graduates. But the best way to promote demand for APTC graduates is to link them with New Zealand and Australian employers. Although the APTC was established in response to Pacific demands for greater access to Australian labour markets, opportunities for migration by APTC graduates have been very limited.

In summary, what our analysis shows is that APTC needs to focus less on outputs (qualifications) and more on outcomes (jobs). The best way to turn qualifications into jobs is to help APTC’s skilled graduates migrate to Australia and New Zealand under both countries’ skilled migration programs. We have developed a policy brief to explain how this might work, and will be blogging about that next.

Read the full Devpolicy Discussion Paper “Worsening employment outcomes for Pacific technical graduate job-seekers” here.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with support from the Pacific Research Program, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are those of the authors only.

About the author/s

Richard Curtain

Richard Curtain is a research associate, and recent former research fellow, with the Development Policy Centre. He is an expert on Pacific labour markets and migration.

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.