Australia’s contractors in international philanthropy: missing in action?

By Rod Reeve

7 February 2017

It will be essential for all development actors to contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It is widely reported that achieving the SDGs will require raising more than $US500 billion of innovative financing per year, additional to increasing global ODA and other measures like overhauling tax rules and improving effectiveness. In this increasingly disruptive world, philanthropy, in all of its forms, will be a major contributor to the SDGs.

Commercial aid contractors are active in delivering around a billion dollars of Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) each year. However, they are almost absent in contributing their expertise to Australia’s other annual billion dollar development activity: privately funded international philanthropy.

I researched what this means for Australians who are interested in the policy and practice of international development, for a paper which will be presented at the 2017 Australasian Aid Conference. My research was partly informed by a survey of 35 CEO-level staff of aid organisations that I led at Ninti One Limited in 2016.

How significant is philanthropy in $ terms?

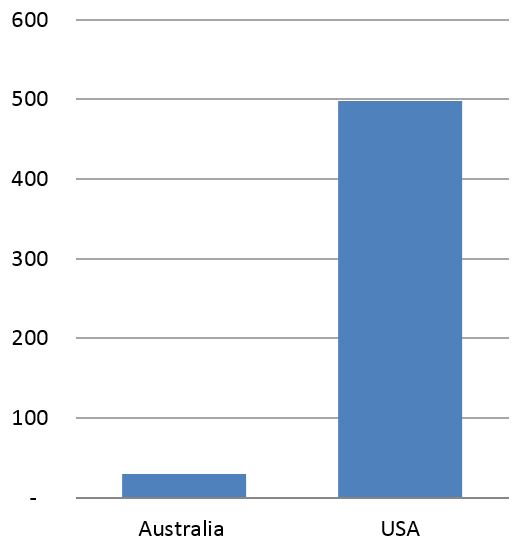

At a philanthropy conference in California last year, I was surprised to learn that total privately-sourced ‘charitable giving’ in the USA was a staggering $US373 billion in 2015. By comparison, Australians gave $A31 billion (individuals plus trusts plus businesses), as is currently being researched by the ‘Giving Australia 2016’ project.

Private ‘giving’ in 2015 ($A billion)

The UK-based Charitable Aid Foundation (CAF) reports that Australia is ranked 11th in the world in terms of individual giving as a percentage of GDP, behind (in order) the USA, New Zealand, Canada, the UK, Republic of Korea, Singapore, India, Russia, Italy, and the Netherlands.

How big is the international philanthropy market?

Community, government and other funding for international use by Australian aid and development NGOs, including non-ACFID members, increased by 7.7% between 2013-14 and 2014-15, from $1.77 billion to $1.91 billion, according to ACFID’s 2015-16 Annual Report. DFAT provided $329 million of this in 2014-15, as ODA. The service providers who deliver programs and activities funded by Australian philanthropy are almost exclusively NGOs: the well-known INGOs plus many hundreds of smaller NGOs.

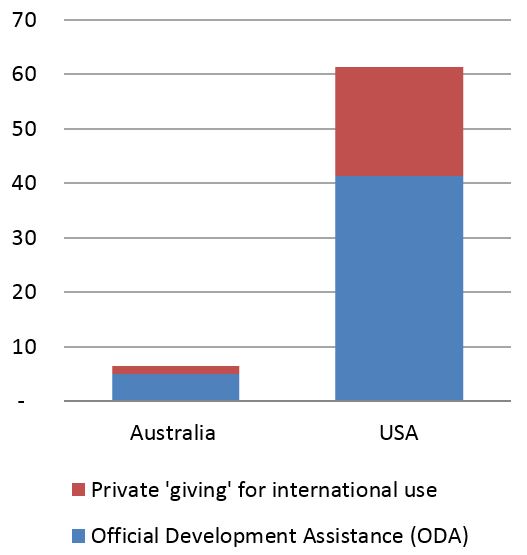

In contrast in the USA, privately-sourced giving for international programs was above $US15 billion in 2015. In terms of ODA, around $US10.5 billion was provided by the US government in the form of grants and cooperative agreements that year. The service providers for these US grants and cooperative agreements included a mixture of commercial aid contractors, NGOs and use of other modalities. Approximate amounts of international philanthropy and total ODA in Australia and the USA are shown below.

International use: private ‘giving’ and ODA in 2015 ($A billion)

Views of NGOs and commercial contractors

As part of a broader survey by Ninti One Limited of 35 CEO-level staff of many of the world’s biggest aid contractors and NGOs from Australia, the USA and six other countries in 2016, four main themes emerged about philanthropic work: (1) the commercial aid contractors who manage sizable portions of Australia’s ODA program do not participate significantly in managing philanthropy (even though some of the large contractors have their own focussed in-house philanthropic activities), (2) NGOs and contractors generally work in silos on Australian ODA-funded work, (3) NGOs tend to share their IP publicly, while contractors do less so, and (4) ODA work is viewed through different lenses by each.

What can be done to use the expertise of commercial aid contractors more fully in international philanthropy?

It seems fairly obvious that that philanthropy and commercial ODA management are complementary because they use the same specialised expertise and approaches to achieve poverty reduction and sustainable development. The siloing in Australian activities also suggests that untapped potential exists for aid contractors and NGOs to work more closely together in delivering outcomes in philanthropic activities and as commercial suppliers to DFAT. However, both funders and commercial aid contractors will need to make some adjustments to the way they work in order to do so.

Funders need to respect the ability of service providers to make a win/win profit. This aligns with the logical argument that says ‘doctors and lawyers make money from helping people, so why not aid workers?’ In addition, funders could be more proactive in encouraging and incentivising collaboration. Collaboration between NGOs has been discussed previously on Devpolicy, however greater possibilities for collaboration exist; for example, between the government (as the provider of ODA) and other funders, which will help to reach critical mass and resultant impact. Philanthropists and funders are always on the look-out for co-contributions or matching funds. Evidence from the USA shows that cross-pollination has beneficial outcomes and impact.

Commercial aid contractors could view philanthropy work as valuable market entry and diversification. Philanthropy is not exclusively the domain of wealthy countries: for example, Myanmar topped the World Giving Index for the last two years. Commercial aid contractors could also reach out to other funders and share their IP more widely. Philanthropic funders may not be aware of the capabilities of the commercial aid contractors. For example, only around 1% of papers presented at the Australasian Aid Conference in Canberra since the conference began in 2014 were authored by representatives of any of the ten biggest aid contractors.

Interestingly, the philanthropy market holds potential for innovation. Most philanthropists have become wealthy by taking risks and not being constrained by ‘government think’. Although much of the public giving is via small funds, some of these funds offer the opportunity for unbridled innovation and risk-taking. In these cases, an entrepreneurial spirit exists, which can consider oft-espoused concepts like innovative funding, unlocking value from remittances, disruptive technologies and matching incubator funds.

Rod Reeve is the Managing Director of the Cooperative Research Centre for Remote Economic Participation; Ninti One Limited; and the Ninti One Foundation.

About the author/s

Rod Reeve

Rod Reeve is the Managing Director of Ninti One Limited.