When it comes to fighting corruption in PNG, it seems the more things change the more they stay the same.

In 2019, when James Marape took over as the nation’s leader from Peter O’Neill (prime minister from 2011 to 2019), the new prime minister promised to prioritise the fight against corruption. Marape pledged to establish an Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC, yet to pass into law), whistle-blower protection (bill passed in February 2020) and a commission of inquiry into the UBS loan scandal (which began earlier this year). Stressing his commitment, soon after becoming prime minister, Marape said [paywalled]:

Our people have had enough and now is the time to tackle the cancer of corruption that has taken hold using the power of prosecution and all other means that we have at our disposal.

If these sentiments sound familiar to those who follow PNG politics, it is because they are. In 2011, after taking over from then Prime Minister Michael Somare, Peter O’Neill also promised to tackle corruption head-on. Like Marape he pledged to establish an ICAC. In the interim he established Investigation Taskforce Sweep, an anti-corruption agency that successfully investigated government corruption until 2014, when it lost its funding after unsuccessfully supporting efforts to arrest O’Neill himself. Despite early optimism around O’Neill’s anti-corruption reform agenda, his government was plagued by corruption allegations, which culminated in his recent arrest related to allegedly purchasing generators without parliamentary approval.

To draw out how well both the O’Neill and Marape-led governments have backed up their anti-corruption sentiments with cold hard kina, in our article recently published in Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies we track how much governments have budgeted for and spent on key anti-corruption organisations (such as the Ombudsman Commission, Auditor General and Fraud Squad).

Our analysis (which builds on previous research) reveals that the O’Neill government initially boosted allocations for and spending on key anti-corruption organisations only to undermine and underfund these organisations as allegations of corruption engulfed his government. In turn, we argue that the O’Neill government’s approach to funding anti-corruption organisations followed a boom and bust pattern that is a feature of other anti-corruption reforms around the world. That is, when a new government comes to power they claim they will address corruption better than their predecessors and initially channel significant resources into anti-corruption organisations (the ‘boom’). However, over time, as accusations of corruption and frustration with anti-corruption efforts mount, politicians underfund and undermine anti-corruption organisations (the ‘bust’).

While, over time, O’Neill’s government starved anti-corruption organisations of funds, in some respects his government did more to support anti-corruption organisations than the current Marape government.

On the face of it, Marape has increased funding for state-based anti-corruption organisations, with most of the key anti-corruption organisations we identify set to receive more money in the 2020 budget. However, in their first budget for 2020, Marape’s government committed less money (in real 2019 prices) to key anti-corruption organisations than O’Neill’s government did in its first budget.

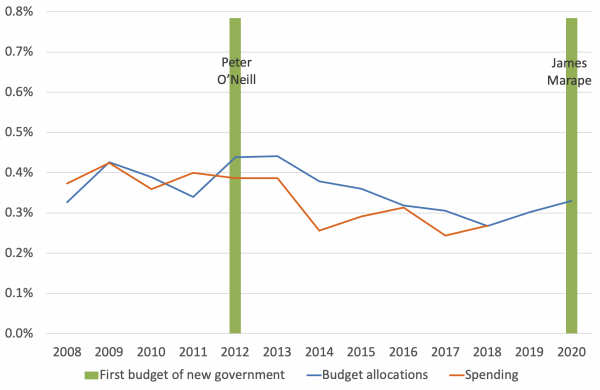

The O’Neill government also contributed more to anti-corruption agencies compared to other areas of government spending in their first budget. Figure 1 below presents allocations and spending for key state-based anti-corruption organisations as a proportion of PNG’s national budget. It shows that between 2013 and 2018 allocations for and spending on anti-corruption organisations reduced relative to other areas of the budget. However, in the O’Neill government’s first budget (2012), allocations increased significantly, rising from 0.34% to 0.44% of the national budget.

Allocations also improved in the Marape government’s first budget, although not as significantly: the proportion of funds allocated to anti-corruption organisations only rose from 0.30% of the total budget in 2019 to 0.33% in 2020. In other words, in relation to other areas of government spending, O’Neill’s government was more committed to anti-corruption organisations in its first budget than Marape’s.

Figure 1: Anti-corruption allocations and spending as proportion of national budget

It is too early to tell what will happen to anti-corruption funding under the Marape government. However, our findings and those from other countries suggest policymakers need to be ready to respond to the tendency of governments to cut funding to anti-corruption organisations over time.

This is particularly the case if Marape continues to be prime minister beyond the 2022 national election, as the longer this government is in power the more pressure it will face to cut funding to anti-corruption organisations. Responding to the boom and bust nature of anti-corruption funding might include supporting civic and diplomatic campaigns aimed at increasing government spending on these organisations. If another prime minister comes to power, policymakers should work to ensure the government boosts resources to key anti-corruption organisations more than Marape and O’Neill did in their first budgets.

Regardless of the political outcomes, governments, donors and others will need to continuously work towards reversing the boom and bust tendencies governments display towards anti-corruption organisations. This could include advocating for legislation that requires anti-corruption organisations to be allocated a minimum percentage of the overall budget. Anti-corruption organisations will still need ongoing funding from the state; however, being able to access some of the funds they help recover could provide them with income when governments reduce their budgets.

Addressing the boom and bust nature of anti-corruption funding is particularly important now the PNG government faces significant financial pressure given the downturn in revenue due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This piece is based on the authors’ article in the Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies journal, “Boom and bust? Political will and anti‐corruption in Papua New Guinea”. All articles in the journal are free to read and download.

Hi Paul,

Thanks for your comments. You are right, the graph presented in the blog shows that as a percentage of the budget spending reduces slightly during the O’Neill government’s first years in office. However, as you will see in the full paper, spending increased for key anticorruption agencies – the Auditor General’s Office and Ombudsman for example.

Still, I think it is important to pay attention to allocations as a key indicator of a ‘boom’ for a few reasons. First, as we note in the paper, underspending can be a function of a lack of capacity as much as political will. Second, as you note we have not seen the actuals for the Marape period which means we cannot compare spending for these two governments. Third, allocations are one (but certainly not only) indication of intent (even if not followed through) and generally get the lion’s share of attention from media and policymakers. Having said this, in the paper and elsewhere – https://devpolicy.org/anti-corruption-and-the-2018-png-budget-20180214/ – we do examine the problem with the gap between allocations and spending.

The O’Neill government did not get the ICAC bill through two Parliamentary readings, but did lay the legal groundwork for the ICAC. In the full paper, we note that the Marape has taken a number of positive anti-corruption measures. For example, the government has commissioned an inquiry into the UBS loan scandal, and appointed anti‐corruption activist MP Bryan Kramer as minister of the country’s police force. We also note that O’Neill also set up Taskforce Sweep in his government’s first year, which was initially successful in investigating corruption. Taskforce Sweep was lauded at the time (a part of the boom period) before it was defunded (as a part of the ‘bust’). Will we see the same dynamic with the new Marape government? Too early to tell, but our analysis and that from elsewhere suggests policymakers and others should be looking out for a bust and be ready to respond to it if/when it comes.

Best,

Grant

Hi Grant

Thanks for the response.

On the evidence of actual practice – the criteria of backing up with ‘cold hard Kina’ you mention – there was no boom. The anti-corruption expenditure share of the budget fell in the first three years of the O’Neill government. By 2017, it had been cut by over a third.

‘A lack of capacity’ to deliver on ‘political will’ is not an issue here – higher shares were actually expended in both 2009 and 2011. So the O’Neill government early years appear to be very big on promises while actually cutting expenditure despite the capacity being present. Is this a boom? Not when tracing the ‘cold hard Kina’ trail. And is it a basis for saying the new Marape government is demonstrating less of a commitment? Maybe the 10% increase (from 0.3 to 0.33%) is just more realistic?

Another interesting comparison will be the current UBS Inquiry and how it goes relative to the abandoned UBS Leadership Tribunal inquiry (and subsequent moves in senior personnel).

With respect

Paul

Hi Paul,

As I’ve noted a ‘boom’ is not just a product of the percentage of the spending allocated to all anticorruption organisations. We do not narrowly define it as such, as I’ve mentioned. Apologies if this is how it comes across in the blog. The boom includes setting up of taskforce, allocations, funding to key anticorruption organisations. etc. The graph above is only a part of the story – which shows the significant rise of allocations.

A key question about capacity is whether the O’Neill government inherited a set of organisations with the capacity to spend their allocations. This is an open question, which the O’Neill government would probably say no, while others will disagree. Arguably, any government has a better chance of shaping that capacity and the ability to absorb funding allocations over time. Still, this is an interesting line of enquiry that deserves more research. In our paper we give the O’Neill government (as we would the Marape government) the benefit of the doubt while noting the problems associated with underspending. I suggest you read the full paper.

Best,

Grant

Thanks Grant and Husnia.

The graph is interesting. Could you add to the analysis the trend based on actual expenditure, not just budget promises?

Looking at actual government behaviour rather than promises appears to tell the opposite story – so one of “bust with minor boom” instead of “boom and bust”.

Specifically, and this is just looking at the graph, for the 2011 to 2012 period, there was no “boom” based on actual expenditure. Indeed, there was a reduction in actual expenditure from 0.4% to about 0.38%. This reduction in actual expenditure continued through to 2017 (with some bumps). So by 2017, it had fallen to about 0.25% – so a very large reduction of over one-third in anti-corruption funding as a share of the budget. And then it started to increase during the tail end years of the O’Neill government. So “boom and bust” on promises, “bust with minor boom” on the actual expenditure figures? Of course, we haven’t as yet seen the “actuals” for the Marape Government.

On legislation, did the O’Neill Government get the ICAC Bill through two successful Parliamentary votes?

With respect

Paul