Goroka Main Market (temporary location), Goroka, 2019 (Credit: Timothy Sharp)

Change and continuity in Papua New Guinea’s marketplaces

By Timothy Sharp

26 September 2019

As places to buy, sell and socialise, marketplaces are a part of daily life for many Papua New Guineans. Marketplaces are critical to food security: they provide a source of income to rural people that is more stable than the volatile and periodic income earned from export tree crops (coffee, cocoa and oil palm), and they are by far the most significant place where fresh food is sold. The sale of fresh food and betel nut in marketplaces also provides money to more Papua New Guineans than any other source. Marketplaces are particularly important for the incomes of women [paywall], who are the dominant vendors and who are frequently poorly remunerated for their labour in export crop production. An increasing number of urban residents are also making a living in marketplaces. In some ways marketplaces have changed very little since they were introduced during the colonial period, however in other ways marketplaces are changing rapidly.

In this blog I present a series of annotated images which tell some of the story of change and continuity in Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) marketplaces.

- The rise of reselling

Historically, most sellers in fresh food marketplaces have been the producers themselves, and wholesale traders or marketplace resellers have been largely absent. It is only in the last 10-15 years that resellers have grown to be a significant group in the urban fresh food marketplaces, although intermediaries have long been present in the betel nut trade [paywall]. In some marketplaces in the large urban centres resellers now outnumber producers. The rise of reselling has seen more urban residents making a living through marketplace selling, such as the woman in this photo who is cutting open bundles of greens that she purchased and is re-tying them into smaller bundles for resale.

- The rise of large scale trading

The scale of trading has also increased. In the past each vendor sold relatively small volumes of produce, however now some producers and wholesale traders transport hundreds of bags of produce at a time. This practice has been around for some time, but the scale at which it is occurring has increased. This image shows bags of sweet potato transported from the highlands region being sold at a wholesale yard opposite the main marketplace (Gordons) in Port Moresby. Several similar wholesale yards exist nearby. The new Gordons Market was under construction in 2019 when this photo was taken.

- More long distance trading

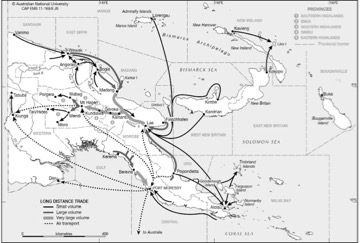

A growing number of commodities in PNG’s marketplaces are now traded over long distances. Sweet potato, potato, cabbages, carrots, onion and citrus are traded from the highlands region to lowland urban centres, particularly Port Moresby, Lae and Madang. Items including peanuts and coconuts are also traded from lowland areas up into the highlands. But no commodity travels further or faster than betel nut (see map). Betel nut is grown throughout the lowlands. Traders from the highlands visit production areas and urban marketplaces to buy this stimulant. They then transport it long distances down rivers, around the coast, and up the highlands highway to urban centres and on to ‘money places’ such as Porgera. Long distance trading was emerging in the 1980s, and since then the volumes and the number of commodities involved has increased substantially.

Betel nut trade routes, 2007-2010

Source: adapted from Allen et al. (2009: 391). Data compiled by R.M. Bourke and Tim Sharp.

- The rise of haggling and competitive behaviour

Haggling and competitive trading behaviour has historically been uncommon in PNG’s marketplaces. But with the rise of reselling, and with more people dependent on trading for their livelihood, it is increasingly common for people to haggle over the price, for vendors to call out to prospective customers, and for resellers to compete with each other to secure produce to sell. Competitive trade practices are particularly evident [paywall] in the betel nut trade, but they are also increasingly common in fresh food transactions. This photo, taken at Kaiwei Market in Mt. Hagen, shows marketplace resellers competing with each other to buy bags of betel nut from wholesale traders located in the bus. Betel nut was undersupplied on this day. When the marketplace is flooded with betel nut there is more haggling between the wholesale traders and the marketplace resellers.

- More male vendors

Women remain the most numerous vendors in PNG marketplaces. Although men have been involved in large-scale production for domestic marketplaces, in the past few men did small-scale selling in the marketplace. There are now a growing number of men selling [paywall] in marketplaces, particularly higher value items such as tomatoes and long-distance commodities such as, in the highlands, coconuts and peanuts.

- Increase in smaller urban marketplaces

The first central urban marketplaces were established in most urban areas in the 1950s and 1960s. Soon after smaller marketplaces began to emerge, and over time these smaller marketplaces have continued to grow in number and size and in the diversity of produce offered. Some smaller marketplaces, often called ‘corner markets’, may have only a few vendors, although others like Seigu Market in Goroka (pictured) are sizeable. Some of the vendors resell produce they have purchased in the main town marketplace, others sell produce they have produced themselves. These marketplaces are busiest in the afternoons when people are returning home from work, and some operate in the late afternoon and evening when the central marketplaces are closed. More house-front stalls (haus maket [paywall]) have also appeared in both urban and rural areas.

- Increase in commercial fresh food production

Production for domestic marketplaces has grown to a more commercial scale, such as this pineapple garden in the Benabena area close to Goroka, Eastern Highlands Province. More people are now dependent on fresh food production as their main source of income, and in some parts of the highlands close to urban centres people have replaced coffee gardens with vegetable gardens.

- The increased sale of ‘store goods’

Most of what is sold in PNG’s marketplaces is domestically produced fresh food. However, in the past decade there has been an increase in the sale of ‘store goods’. This includes items such as rice, salt, oil, candles, cigarette lighters, soap, lollies, soft drinks, cigarettes, plastic bags, second-hand clothes, and mobile phone credit. In some marketplaces items such as thongs, pirated DVDs, medicines, and torches are also sold. Cooked food produced from store goods such as sausages, lamb flaps and flour balls, is also common.

- Some things haven’t changed

One aspect of marketplaces that has not changed is that all fresh food is sold in piles or bundles, rather than by weight. The piles are of various sizes, and although the size of a, say, PGK2.00 pile of sweet potato may increase or decrease over the course of a day, the price itself does not. There is no such thing as a PGK2.40 pile of sweet potato. It has become common for vendors to give some customers ‘extra’ produce [paywall], on top of what they purchase.

Marketplaces also continue to be very important places for women to earn income. Although certain types of trading are dominated by men, most vendors today remain women.

PNG’s marketplaces also remain important social venues – places to meet with friends and relatives, to share news and gossip, and pass the day.

Some of the changes reported in this blog are discussed in a special issue of Oceania on Marketplaces and Morality in Papua New Guinea.

Research on marketplaces and women’s entrepreneurship is ongoing as part of the Pacific Livelihoods Research Group’s ACIAR-funded project – “Identifying opportunities and constraints for rural women’s engagements in small-scale agricultural enterprises in Papua New Guinea”.

About the author/s

Timothy Sharp

Timothy Sharp is a research fellow within the Pacific Livelihoods Research Group at Curtin University, Perth.