Civil society and development: moving from de Tocqueville to Gramsci

By Grant Walton

17 August 2015

Development agencies expect a lot from civil society – from providing social services to fighting corruption. It’s little wonder that in 2003 civil society was dubbed ‘the new superpower’ by then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Today, it is considered a key partner in shaping and implementing the post-2015 sustainable development agenda.

With the weight of the world bearing down on its shoulders, it’s important to examine the concept of civil society to get a realistic sense of its potential and pitfalls.

There are two key ways to understand civil society. The first perspective derives from Alexis de Tocqueville’s (1805-1859) sanguine assessment of civil society in the United States during the 19th century. According to followers of de Tocqueville, civil society is an ‘autonomous area of liberty incorporating an organizational culture that builds both political and economic democracy’ (McIllwaine, 2007: 1256; pay walled). In this perspective, civil society is considered a counterweight to, and essentially separated from, state power and market forces.

This approach to conceptualising civil society is reflected by many development organisations. Australia’s DFAT considers civil society as:

a growing range of non-government and non-market organisations through which people can join together to pursue shared interests and values for their communities and nations.

Like many development actors, DFAT writes about civil society in glowing terms, referring to it as an ‘agent of change’. It states that, ‘NGOs [which are often conflated with civil society but are only one component] can be powerful agents for change and are a key development partner’. And DFAT is not alone in this. A recent paper by Bronwen Dalton from the University of Technology Sydney examines the definitions of civil society by a number of think tanks, most of which reflect DFAT’s optimistic assessment.

Yet in many instances, particularly in developing countries, civil society fails to live up to these ideals. For a start, society is often not very civil. We’ve seen that most vividly in Syria, where there is great uncertainty about which groups are civil and which are not. In addition, the boundaries between civil society groups, the state and market are often blurred. Civil society organisations can be co-opted by the state, such as those coined Government Organised NGOs (GONGOs), which are dependent on government funds. The private sector can also significantly shape civil society organisations, reflected in the categorisation of Business Organised NGOs (BONGOs) and Business Interested NGOs (BINGOs).

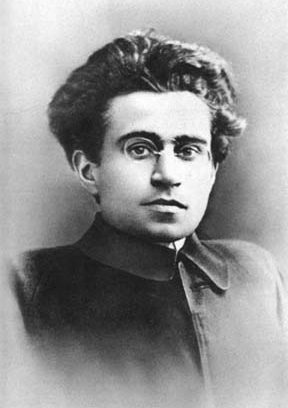

These conceptual issues have led some to draw on insights from Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), whose writings focused on three aspects of civil society, differentiating his analysis from de Tocqueville’s. First, he stressed the fluidity of relations between the state and civil society – arguing that as civil society (trade unions, media, religious organisations, etc.) and political society (police, army, legal system, etc.) often overlap, one cannot be understood without the other. Indeed he conceived the state as comprising both civil and political society. Second, Gramsci argued that civil society consists of elements that resist or reinforce hegemonic ideas about economic and social life. For Gramsci, civil society is a jumble of groups whose ability to benefit society is dependent on context and the nature of dominant ideas.

Finally, Gramsci was also concerned with international forces. Social theorist Bob Jessop’s insightful analysis shows how Gramsci believed that: ‘national states are not self-closed “power containers” but should be studied in terms of their complex interconnections with states and political forces on other scales’ (2005: 425). Other scholars, particularly geographers, have used this insight to study the interconnection between local and international civil society groups. Some suggest that these interconnections help social and environmental movements, while others disagree.

Gramsci was a Marxist, and considered the role of civil and political society in terms of class relations. So it’s not surprising that his theory of civil society is less drawn upon by development agencies than de Tocqueville’s, who was a classic liberal.

However, some believe that the world of development is starting to take a more ‘Gramscian view’ of civil society given some of the failures of policies aimed at supporting civil organisations.

Human geographer Cathy McIllwaine writes [pay walled] that:

the role of civil society in the development policy arena has moved from one of adulation to one of much greater circumspection about what they can actually deliver in practice (2007: 1262).

She believes this ‘falling out of love’ with civil society could be considered a shift towards a ‘more realistic Gramscian interpretation of civil society’ (2007: 1263).

Attempts to deal with both the uncivil and civil elements of society are reflected in policy discussions about anti-corruption movements. Transparency International’s influential Source Book – a guidebook used by a range of policy makers and activists around the world – cautions that:

Many civil society groups are single-minded in the pursuit of their particular cause and have no interest in balancing their aspirations within the wider public good (Ch 15; p. 131).

It also notes that the organisation will only work with groups that are ‘expressly non-partisan and non-confrontational’ (p. 135) – an approach that attempts to separate civil society from the political dimensions of the state.

Neo-Gramscians would support efforts to identify civil and uncivil elements of society, but many would question whether civil society can be as ‘non-partisan’ as this document suggests. Indeed, in this edited volume, academic Luis De Sousa notes that, despite its apolitical orientation, Transparency International has involved politicians in their local chapters and requires state support for their continued operations. Anti-corruption advocacy ultimately requires engaging with politicians and politics – which can mean taking a political side (even if actors try to appear non-partisan). It’s difficult to extract politics from advocacy.

This example highlights how some of Gramsci’s concerns have been reflected in development policy while others have been side-stepped.

Empowering civil society to promote social change is fraught, and raises many of the issues that Gramsci was concerned with almost a century ago. Given the importance development actors place on supporting civil society, practitioners could benefit from thinking through the insights offered by this Italian Marxist. Even if they don’t agree with his politics.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

About the author/s

Grant Walton

Grant Walton is an associate professor at the Development Policy Centre and the author of Anti-Corruption and its Discontents: Local, National and International Perspectives on Corruption in Papua New Guinea.