COVID-19 in Papua New Guinea and an imagined threat to Australia

By Monica Minnegal and Peter Dwyer

10 March 2021

On 6 March The Weekend Australian reported that Queensland will fast-track the AstraZeneca vaccine into the Torres Strait, as the COVID-19 outbreak in Papua New Guinea worsens and Australian authorities grow increasingly concerned about the porous northern border (see also here).

Through February and early March, reported COVID-19 cases in PNG increased by 73 percent, from 865 to 1,493. The death toll increased from nine to 16. By global standards these numbers are small, though by Pacific standards they are large. However, within PNG the rate of testing has been low and it is likely that many cases have gone unreported. The parlous state of PNG’s health facilities suggests that the country may be already approaching a limit to possible containment (here, here and here). There are concerns, moreover, that PNG could export the virus eastwards to other Pacific nations and that the outbreak may have geopolitical implications.

It is in this context that Queensland is acting on behalf of its own citizens, both those on islands like Boigu and Saibai that are less than 10 km from PNG’s Western Province, and those on the mainland to the south. As Australians, the people of Boigu and Saibai have potential access to material conditions and services like those available to residents of the mainland. The privileged lifestyles of the latter, however, are beyond the experience and the reach of their Western Province neighbours who ‘endure a near-total failure of governance and service delivery’.

Queensland’s concern is valid. The response, however, may be misguided.

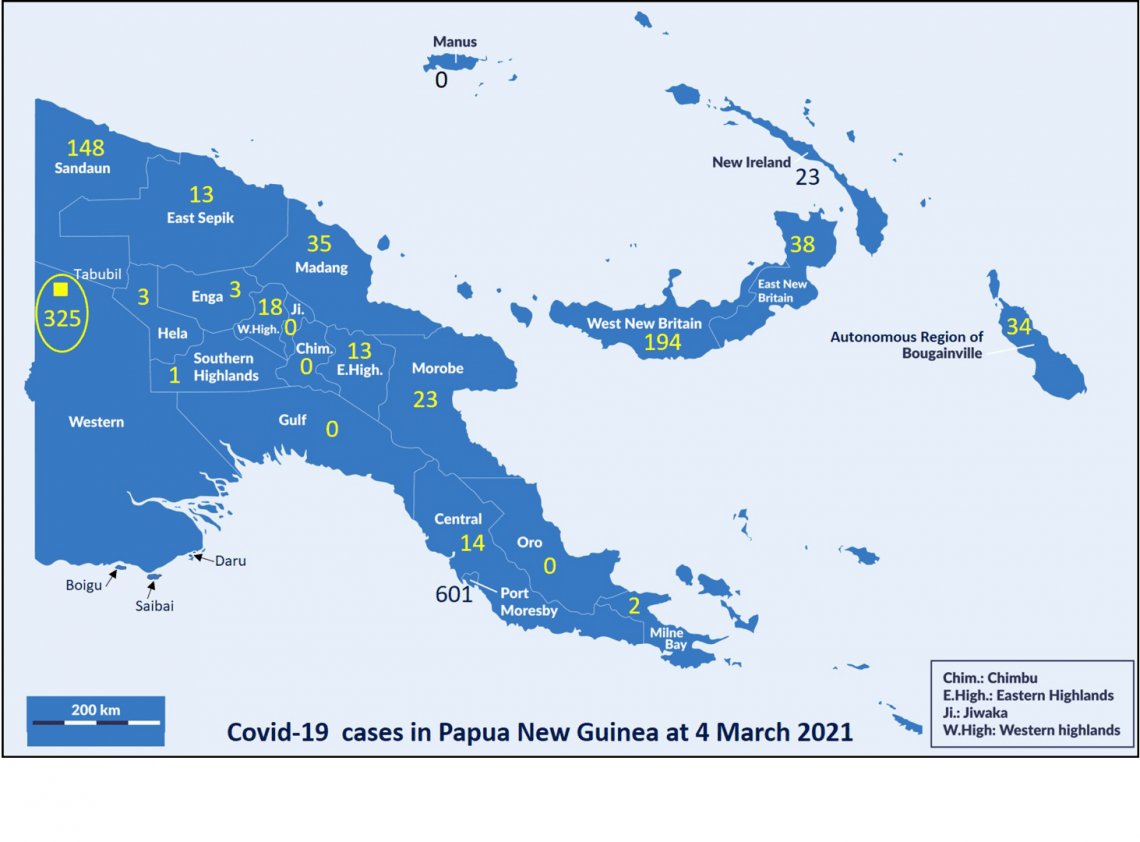

The map at the head of this article shows the distribution of reported COVID-19 cases in PNG at 4 March 2021. Cases have been reported from the National Capital District (Port Moresby and surrounds) and 16 of the other 21 provinces. The distribution is very uneven. Three provinces – National Capital District, Western Province and West Sepik – have contributed 479 (76 percent) of the 628 new cases recorded in the past five weeks. West Sepik jumped from a total of two to 146 cases in those weeks, with outbreaks among hospital staff and at correction centres.

For Queensland, however, Western Province is its nearest neighbour and must be focal. With 325 reported cases at 4 March, this province is second only to National Capital District in its tally of COVID-19 cases. But, as indicated on the map, all of those cases were recorded from the north of the province, with all but four from the Ok Tedi mining town of Tabubil and some of its surrounding villages.

Present infection statistics provide no direct evidence that coastal communities of Western Province pose a COVID-19 threat to Australia. Far from it. None of the COVID-19 cases in that province has been detected from coastal communities close to Australia; to the contrary, they have all been detected more than 350 km north of the northern limit of Australia.

Gulf Province, encompassing coastal communities to the immediate east of Western Province, has not yet recorded any cases of COVID-19. The current threat to Queensland comes from the north of Western Province, and it comes from the well-off rather than from the desperately poor. In early March, five cases detected in the north Queensland city of Cairns were Ok Tedi workers who had arrived by charter flight from Tabubil. They were not the first COVID-carrying, fly-in fly-out, passengers to come from PNG.

Ok Tedi Mining Ltd. has been monitoring its work force since August last year. Queensland can test international arrivals and quarantine them as needed. Therefore, a potential threat from that quarter can, presumably, be managed.

But what should happen in the south where, at present, there is no evidence of imminent threat but where there is always the potential for a threat to emerge? It is the potential that should be managed. But that potential is not located on Australian islands in Torres Strait. It is located nearby on the mainland of PNG. Health facilities in the south of Western Province are in a disgraceful state. Cases of TB are already at a shocking level. If COVID-19 does get a hold here then, irrespective of the dedication of medical staff, there is no infrastructure and there are no resources to hold it at bay.

This is where Queensland, and Australia, should prioritise effort. Targeting the urgent health needs of people in the south of Western Province would allow simultaneous, and much needed, monitoring of COVID-19. It would show, first, whether there was actually a need for greater intervention both within and beyond the south of Western Province and, subsequently, direct attention to modes of intervention that did not have the appearance of constructing a wall of immune bodies to guard the lives of southerners. The reciprocity implicit in serving one’s own needs and interests through contributing positively to the needs of others would resonate well with local understandings in PNG.

The present proposal to vaccinate Australian citizens who live close to PNG will be, without doubt, beneficial to those people. It might be also imagined as safeguarding people who live in Cairns or Brisbane, though it is far from necessary for this. It will not, however, do anything at all toward improving the health of, or enhancing relations with, Papua New Guineans who live just a short boat trip away. These are men, women and children who have none of the advantages that sometimes accrue to their friends and relations who, by the accident of a line drawn on a map, became citizens of a different country.

About the author/s

Monica Minnegal

Monica Minnegal is an Associate Professor in the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Melbourne.

Peter Dwyer

Peter Dwyer is an Honorary Senior Fellow in the School of Geography at the University of Melbourne.