Cut the cut: why the Turnbull government should stop reducing Australian aid

By Terence Wood

18 November 2015

Among aid supporters, Tony Abbott’s time as prime minister won’t be remembered fondly. First, there was the disintegration of AusAID for no good reason (not even those invented post-hoc). And then the largest ever cuts to Australian aid. Cuts that were extreme even by the turbulent standards of international aid flows. Cuts that weren’t justified by Australia’s deficit (aid is too small a share of federal spending to have a real impact). And cuts that were so sudden that nothing other than crude heuristics could guide where they fell. Different political parties have different beliefs, and it is fair enough that these influence policy choices, but governing well also means making major policy changes only when they are justified, and making them on the basis of evidence. Justification and evidence were notably absent from the Abbott government’s treatment of aid.

Among aid supporters, Tony Abbott’s time as prime minister won’t be remembered fondly. First, there was the disintegration of AusAID for no good reason (not even those invented post-hoc). And then the largest ever cuts to Australian aid. Cuts that were extreme even by the turbulent standards of international aid flows. Cuts that weren’t justified by Australia’s deficit (aid is too small a share of federal spending to have a real impact). And cuts that were so sudden that nothing other than crude heuristics could guide where they fell. Different political parties have different beliefs, and it is fair enough that these influence policy choices, but governing well also means making major policy changes only when they are justified, and making them on the basis of evidence. Justification and evidence were notably absent from the Abbott government’s treatment of aid.

Now Tony’s tenure is behind us, the big question is whether Malcolm Turnbull’s government will be kinder. There are reasons to hope it will. Turnbull himself appears more capable and considered. And Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s power has increased. She didn’t appear to support the last aid cuts and she’s shown that she cares about important development issues such as empowering women. Also, the appointment of Steven Ciobo as Minister for International Development and the Pacific is a good sign—a signal there will be more concern for aid.

Yet Ciobo’s appointment is only a signal. And there is a much more tangible act the government could take to show it cares about aid: it could abandon the aid cuts planned for next financial year.

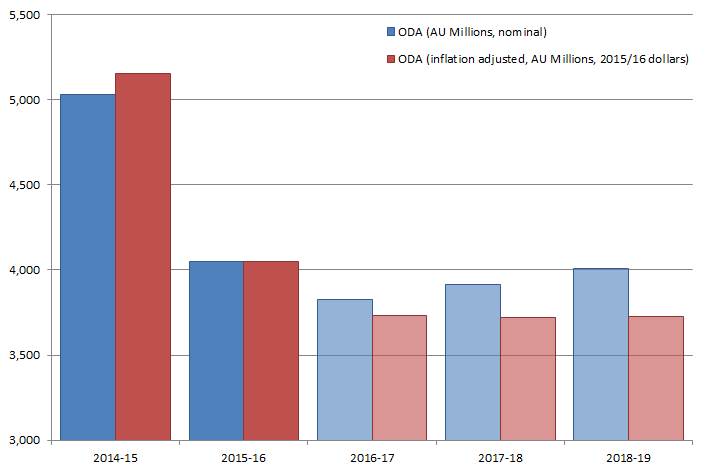

The chart below uses data from the 2015 budget. The blue bars show government aid in non-inflation adjusted dollars, the red bars show the budget once inflation is adjusted for. The first pair of bars shows aid levels prior to the 2015 cut. The second pair shows current aid levels. The subsequent, translucent pairs show planned aid over future years as signalled in the 2015 budget. As the chart shows, aid is currently set to take another hit next year, falling by a further $224 million dollars.

This is not as large as the last cut, but it’s still substantial. It’s more aid than Australia gives Solomon Islands, the third largest recipient of Australian aid. It’s more than the entire Australian country-allocated aid budget for all the countries of Polynesia and Micronesia combined. It’s more aid than Australia gives directly to all the countries of Africa and the Middle East (source: Table 2, p. 5, here).

It’s true that, after next year’s cut, the aid budget is projected to grow so that by 2018 it will almost be back to current levels. But these apparent gains are only rises in nominal amounts–increases in line with projected inflation. As the red bars show, once inflation is adjusted for, aid is set to go down in 2016, and stay down thereafter.

Figure 1: Actual and budgeted Australian Official Development Assistance (ODA)

(Data and source details here.)

(Data and source details here.)

There is an ongoing humanitarian catastrophe in the Middle East. Parts of the Pacific are facing major drought and other climate problems from an El Niño weather event. The broader development problems of countries like Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands remain as acute as ever. There is no shortage of need for this money. Here in Australia it won’t make a difference though. $224 million dollars is only 0.05 per cent of total federal spending (less than 5 cents out of every hundred dollars the federal government spends). This is so small an amount as to have no material impact on Australia’s fiscal health.

The cut is unnecessary, and the Turnbull government should abandon it, and then, at the very least, increase the aid budget in line with inflation over coming years. Ideally, the government would do much more than this, and it could. But if braver moves are beyond it, canning the coming cut would be a start.

It would be smart politics too. Australians may have been OK with the last cut, but polls show that a clear majority of Australians support or strongly support Australia giving aid (this is not just true of the country as whole but also Coalition supporters) and patience with an ongoing, tight-fisted approach to aid may eventually run out. Meanwhile, NGOs are gearing up to campaign intensively around the next election. Further reducing aid would provide great campaign fodder. Not reducing it on the other hand would go a long way to defusing matters. Internationally, abandoning the cut would set this government apart from its predecessor and go some small way to fostering a kinder image of Australia.

Most important though, is simply the fact that there are many parts of the world where this money is needed. Aid isn’t a panacea, but when given well it helps, and if the current government is concerned with development and global poverty it should cancel the cut.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His PhD focused on Solomon Islands electoral politics. He used to work for the New Zealand Government Aid Programme.

About the author/s

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.