(Credit: ABC)

Development and the 2019 election: the partisan divide

By Stephen Howes

10 May 2019

In the forthcoming Australian federal election, now only days away, there are three sharp international development policy differences between the two major parties. They relate to aid, refugees, and climate change.

Aid

Neither party has talked much about foreign aid. Despite this silence, there are major differences. The Liberals have telegraphed their aid intentions via their 2019-20 budget forward estimates. Labor has not provided a specific dollar figure, but is foreshadowing some increases, possibly major. Senator Penny Wong, who will be Foreign Minister if Labor wins, said in her Lowy speech on 1 May that “Labor will increase official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income every year, starting with our first budget.” The same policy is included in the official Labor policy website. What does it mean? A strict interpretation is that aid/GNI would be increased by at least 0.01 percentage points every year, since those are the units in which that ratio is conventionally measured. More loosely interpreted though, the commitment could just mean that the aid/GNI ratio would only be increased by an infinitesimal amount every year.

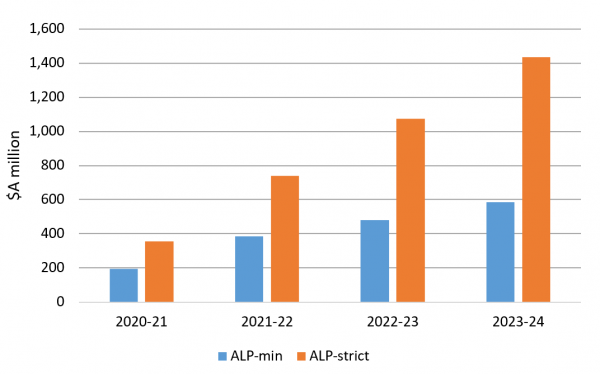

Labor should definitely be held to account to the former interpretation, since it is the most natural one. But either way (in the graph below, “ALP-strict” in which aid/GNI increases by 0.01 percentage points a year; or “ALP-min” in which aid/GNI is stabilised), there should be significantly more aid under Labor than under the Coalition (which is only undertaking to index aid to inflation). In the first year, 2020-21, the projected additional aid under Labor is $200 to $350 million, and by 2023-24 it is $600 million to $1.4 billion.

Additional aid promised by Labor

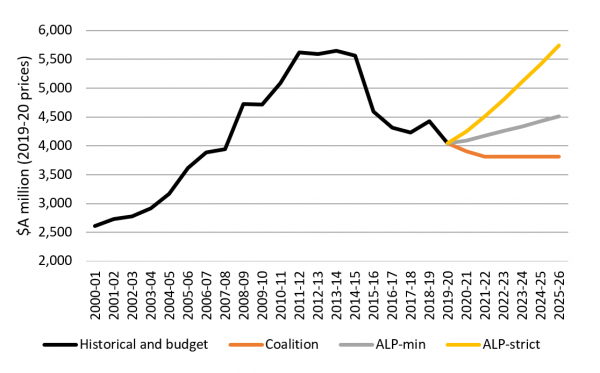

The analysis above is in current dollars. The three possible future trajectories for inflation-adjusted aid – one for the Liberals (or Coalition) and two for Labor – are shown in the next slide. At a minimum, Labor is committing to start reversing the Coalition cuts. Under the most natural interpretation of the Labor/Wong commitment, those cuts would be fully reversed by 2025-26.

Potential future aid trajectories

It remains to be seen whether Labor will actually include its aid promises in its election promise costings, which it has undertaken to release today. It would be disappointing if they don’t, but the commitment itself, even if vague, surely puts Labor ahead of the Coalition on foreign aid.

Refugees

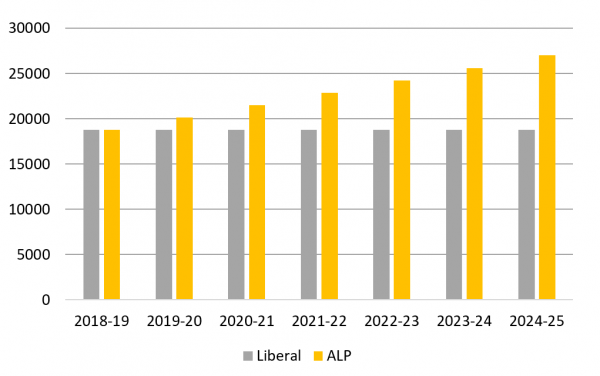

Foreign aid is obviously important for Australia’s international development effort, but our willingness to accept refugees is no less so, especially given the fact that the world is facing its worst humanitarian crisis since the Second World War. Refugees are, almost by definition, the most exploited people in the world. The two parties have very different policies on their willingness to accept them into Australia, as shown in the next figure. The category is actually “humanitarian intake” which includes “refugees and those in refugee-like situations.” The Coalition has, to its credit, in recent years increased our humanitarian intake, but it is not planning to go any further. By 2024-25, we would have a humanitarian intake that is 7,000 higher under Labor than Liberals.

Humanitarian intake proposed by Liberals and Labor

Historically, the Labor commitment, if realised, would be a major achievement. It would increase the number of refugees allowed into Australia to close to one per 1,000 Australian residents, a level we have rarely come close to in the past, let alone sustained.

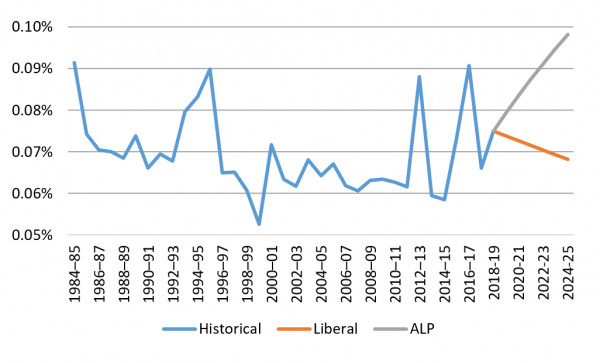

Humanitarian intake as a percentage of the Australian population

Emissions reduction

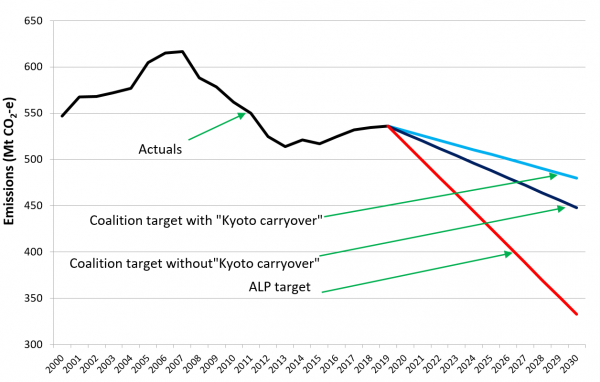

Some would say our contribution to mitigating climate change is the most important of all the efforts we can make in relation to international development. Here again, there are important differences between the two major parties, shown in the next figure. The Liberals are promising to cut Australia’s emissions by 26-28% compared to 2005 levels, by 2030; Labor by 45% (and by 100% by 2050).

It is not easy to compare the two targets, because of the different ways in which they might be achieved. The Coalition has said that it will use the so-called “Kyoto carryover” (created by the over-achievement of our ridiculously easy Kyoto target) to help us reach our 2030 target, but not international credits (payments to other countries and/or overseas projects in lieu of domestic emissions reductions). Labor has taken the opposite position: yes to international credits, but no to the Kyoto carryover.

Liberal and Labor emissions targets

Despite this complexity, unless we achieve most of our emissions reduction target via international purchases, the Labor target is certainly the more ambitious one, the one that would be harder to reach.

Conclusion

I’m not focusing on the Greens, who are promising even more generous and ambitious development policies than Labor, in part because the three areas I’ve highlighted are ones in which decisions are made by executive fiat rather than legislative bargaining. Hence they are ones in relation to which the Greens will lack influence, even if they hold the balance of power in the Senate.

Development has not traditionally been an area of partisan divide. The was bipartisan consensus on aid and refugees till 2012, and the difference on emissions targets only emerged in 2015.

There is no obvious reason why Labor should come out ahead of the Liberals on these three policies. Historically, the Liberals have led on several of them. But we are where we are. It certainly makes this election an important one for anyone who cares about international development.

Notes: Labor’s humanitarian intake commitment for 2024-25 is 27,000. I take 26% as the Liberal emissions target (rather than 26-28%), as this is the number emphasised by the PM. It is assumed that the humanitarian intake and emission reduction targets are approached in a linear manner. On aid, it is assumed that after the forward estimates, the Liberals keep aid constant in real terms, as they do in the forward estimates from 2021-22. Data available in this spreadsheet.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.