Election 2016: how do the parties compare on aid and development?

By Camilla Burkot and Stephen Howes

24 June 2016

This year’s federal election campaign, one of the longest in Australian history, is mercifully approaching its finish line. Yet despite having so much time to cover a range of issues, relatively little has been said publicly by the parties on aid and development issues (though aid and foreign policy did feature prominently in this week’s National Press Club Deputy Leaders’ debate).

This year’s federal election campaign, one of the longest in Australian history, is mercifully approaching its finish line. Yet despite having so much time to cover a range of issues, relatively little has been said publicly by the parties on aid and development issues (though aid and foreign policy did feature prominently in this week’s National Press Club Deputy Leaders’ debate).

To help fill the gap, the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID) solicited responses from Australian political parties to 10 questions, spanning the purpose of aid, aid volumes, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), humanitarian action, and more. Both major parties responded, as did the Australian Greens and Family First. A summary comparative table can be found here; as can the detailed responses from the Liberal Party, Labor, the Greens, and Family First.

In this post, we compare their responses on some key areas for aid effectiveness and development policy.

How much aid should Australia give?

While all four parties are more or less on the same page with the purpose of aid, the question of how many dollars they would put on the table elicited more varied responses.

The Liberal Party statement reiterated that it will refrain from committing to a “prescriptive, time bound aid target” until the Australian economy is on firmer footing (something that appears to be elusive at best), allowing only that the ODA budget will increase by the CPI from 2017-18.

Labor affirmed its existing commitment to reaching 0.5% of GNI, but also hedged when it comes to establishing how quickly that will happen, blaming the Liberals for making cuts “so deep that it is impossible to fix the aid program quickly”. If the ALP’s May announcement is anything to go by, don’t expect to see a radical difference from the Coalition here. Labor appears to be promising just another $200 million a year.

The Greens have by far the most ambitious target of the four parties for aid, planning straight line increases to reach 0.7% of GNI by 2025-26. Citing the Parliamentary Budget Office, they estimate this will cost $4.33b over the forward estimates by 2018-19 (according to their submission to ACFID) or $7.97b over forward estimates by 2019-20 (according to the Greens website and media sources).

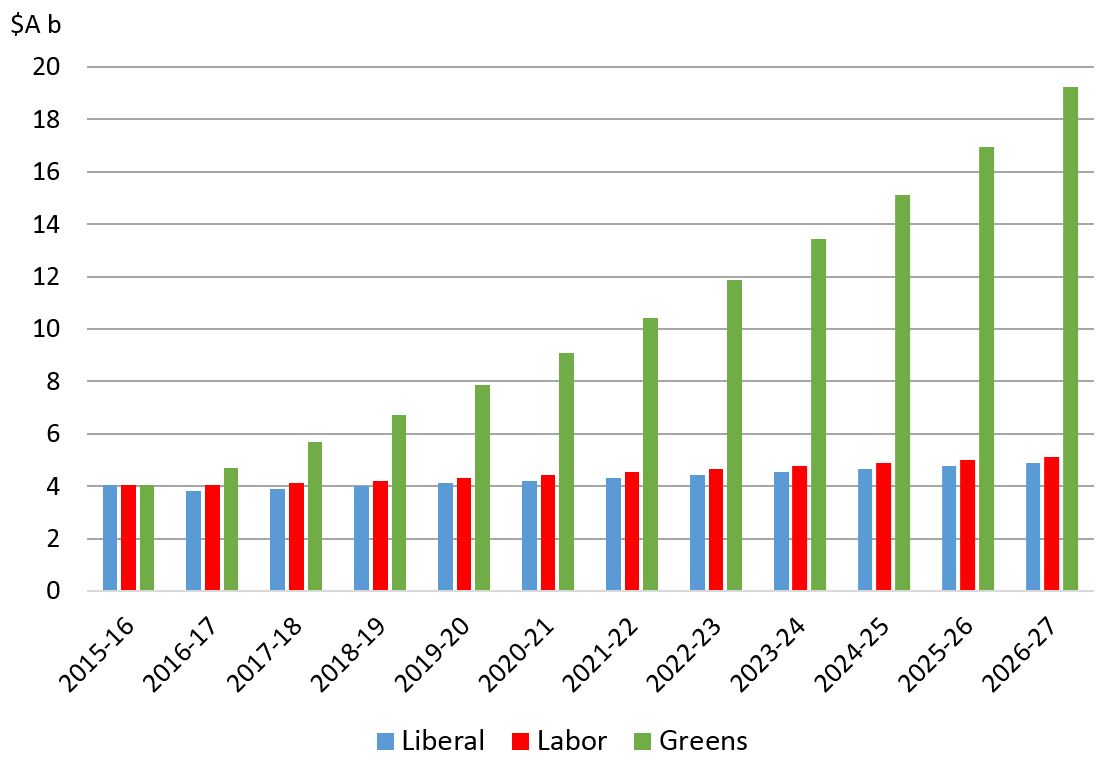

Below we extrapolate the commitments of the Liberal, Labor, and Green parties out for a decade, as best we can, by assuming current policies remain in place. The Greens soon leave the other two parties behind. But then aid budgets are one of the few things ruling parties don’t have to negotiate with cross-benchers, so the Greens’ influence on aid volumes will be marginal.

Projected aid budgets under Liberal, Labor and Green commitments ($A billion)

Assumptions: Budget and forward estimates for the Coalition, and then aid increased in line with CPI. For Labor, aid increased by an additional $800 million over four years relative to the budget and forward estimates (see this post for details) and then increased with CPI. Aid reaches 0.7% of GNI by 2026-27 under the Greens, with fixed annual increases in the ODA/GNI ratio starting this year to get there. CPI and nominal GDP (GNI) growth figures extrapolated from latest budget projections.

What about transparency and evaluation?

On the issue of transparency, the Liberals assert that they will “continue to deliver a transparent aid program” by publishing three annual documents: the new Orange Book (summary of the aid budget for the coming year), the Performance of Australian Aid report (a look back at the previous year), and the Green Book (statistical summary). Interestingly, they also refer specifically to delivering a program that is “in line with the International Aid Transparency Initiative [IATI]”. Presumably, this means that action will at last be taken to make project-level data currently submitted to IATI accessible: currently it’s not.

The ALP and the Greens both intend to legislate as a way of improving effectiveness and transparency. As announced by Deputy Leader Tanya Plibersek more than six months ago, Labor promises legislation that will include arrangements for the independent evaluation of the aid program, as well as enhanced monitoring and reporting on aid effectiveness.

The Greens’ proposed legislation (which will augment the aid bill Senator Lee Rhiannon introduced last year) sounds much like British legislation, and would require an annual ministerial report to Parliament on how Australia is performing on increases in aid spending, aid allocations, and how those allocations are addressing the SDGs. On their party website, the Greens also look to Britain as a model on independent evaluation, suggesting that the Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) is “lacking teeth compared to Britain’s Independent Commission on[sic] Aid Impact” because ODE is located within DFAT.

How should Australian aid be managed?

Nearly three years after the re-integration of AusAID and DFAT, the role and effectiveness of the latter is still clearly a hot topic for some. Tanya Plibersek had earlier talked of recreating AusAID if Labor won after one term, but that seems to have been given up on. In the final, open-ended question of ACFID’s questionnaire (more on that below), the ALP stated it would “re-evaluate the role of international development within DFAT”, and highlighted issues of departmental culture and practices as well as retaining aid expertise (all concerns which came through loud and clear in responses to our aid stakeholder survey last year).

The Greens would go one step further, and seek to not only stop the clock but wind it back by re-establishing an independent department to manage Australian aid, with its own cabinet-level Minister, separate from what it calls the “conflicting interests” of DFAT.

Parting shots

Potentially the most interesting question that ACFID asked the parties to respond to was the final one: “Is there anything else you’d like to tell us?” As political campaigns show time and again, it’s those less-scripted moments and open-ended questions that often provide valuable insights into what candidates and parties really think.

Like much of the rest of its response, the Liberal answer was predictable: reiterating its commitment to gender equality initiatives under Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s leadership, and highlighting, yet again, the innovationXchange. By contrast, despite taking a potshot at the innovationXchange in a recent media release, Labor’s response to ACFID was mum on the future of the controversial office.

In addition to putting the status of aid within DFAT under the microscope, Labor used the last question to call for better use of Australia’s diplomatic network to advance development efforts.

In a rare moment of commonality with the Liberals, the Greens’ response too dedicated a paragraph to the issue of gender equality. They also advocate a Tobin tax on financial transactions to raise funds to address global poverty and climate issues.

Family First wins the award for the quirkiest final answer of the four, which asserted that aid should go to NGOs rather than foreign governments, on the somewhat dubious basis that this “better insulates aid funding from potential corruption via government officials” – thereby unfortunately appearing to reinforce the discredited notion that corruption is a significant risk in aid, as well as contradicting its own position that “NGOs [should] remain independent from government”.

In summary

The Coalition and Labor stand together on volumes; the Greens and Labor are united on the need for aid legislation. And everyone seems to support more transparency.

Camilla Burkot is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre. Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre.

About the author/s

Camilla Burkot

Camilla Burkot was a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre, and Editor of the Devpolicy Blog, from 2015 to 2017. She has a background in social anthropology and holds a Master of Public Health from Columbia University, and has field experience in Eastern and Southern Africa, and PNG. She now works for the Burnet Institute.

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.