Tongan participant in the Seasonal Worker Programme (DFAT/Flickr/CC by 2.0)

For Tonga, Australian labour mobility more important than aid and trade combined

By Stephen Howes and Beth Orton

21 January 2020

A World Bank study of Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) workers in 2015 estimated that Tongan seasonal workers made on average net earnings of A$9,759. This estimate is calculated based on the workers’ reported total earnings in Australia minus their expenses in Australia minus estimates of the earnings and income in Tonga that they had to forgo to be in Australia. We don’t have a more recent estimate than 2015. If anything, one would expect the amount to have increased in line with increases in the minimum wage.

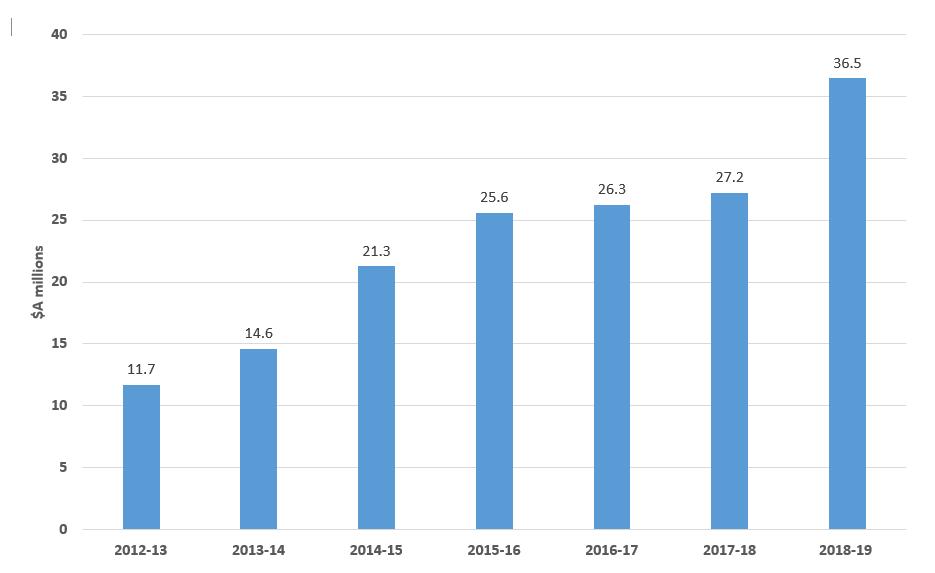

The number of Tongans coming to work in Australia through the SWP has grown rapidly. The scheme only started in 2008. By 2012-13, there were 1,200 Tongans in the SWP, and by 2018-19 3,740. Combining these two figures — average net earnings, assumed constant, and the growing number of workers — gives estimates over time of the aggregate net earnings of Tonga’s SWP workers. As you can see from the graph below, Tonga’s aggregate net SWP earnings have more than tripled from just $11.7 million in 2012–13 to $36.5 million in 2018–19.

Estimated aggregate net earnings of Tongan seasonal workers in Australia

We can compare SWP earnings to other major sources of foreign exchange that Tonga derives from Australia. Last year Australia provided (Table 6) Tonga with $28.9 million in aid. Also last year, Tonga is reported to have exported $2.3 million worth of goods to Australia. As you can see from the graph below, in 2018-19, SWP net earnings exceeded Australian aid to Tonga and imports from Tonga both separately and combined.

Tonga: net earnings from SWP, aid and trade in 2018-19

Tonga is the first Pacific nation to achieve this milestone, and it did so just last year. Of all the Pacific nations, Tonga is the one that has embraced the potential of seasonal work most enthusiastically. (This article attempts to explain its success.) In 2018, we estimated that 13% of the Tongan population aged 20 to 45 left the country each year to work on either Australian or New Zealand farms. And that share would have grown since.

It’s not only an impressive achievement by Tonga, but also the sort of fact that should change the way we think about Australia’s relationship with the Pacific. Aid is important but more aid is not the answer to the Pacific’s development challenges. Moreover, aid, whatever the benefits to Australia, costs the Australian taxpayer. Labour mobility by contrast benefits the Australian farmer, and the Australian economy more broadly.

The Pacific is not, in general, a trading region. Tonga has long had duty-free access to Australia, but is unable to take much advantage of it. Tourism is important to several Pacific nations, including Tonga, but very few Australians holiday in Tonga.

Despite the growing importance of labour mobility, Australian groups who advocate for development in Australia have been very quiet to date on the subject. It’s time for such organisations as ACFID, IDCC, and Results Australia to take up this issue. There’s a lot to be done. Temporary schemes like the SWP work well for Tonga, but suit other Pacific nations much less well. We need to move beyond temporary and start talking about expanding permanent migration options.

There are also no fewer than three policy processes and inquiries in Australia currently underway to which this striking fact about Tonga is relevant. The first is the government’s preparation of its new International Development Policy. To its credit, the new policy is meant to go beyond aid, and look at “expanding opportunities for Pacific workers to fill workforce shortages in regional Australia”.

The second is the parliamentary inquiry into “Australia activating greater trade and investment with Pacific island countries”. It would be better if labour mobility had been in the title of this inquiry, but at least its terms of reference briefly states that this inquiry (of the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade) will examine opportunities to strengthen “employment links”.

Finally, the Senate Select Committee on Temporary Migration is inquiring into the impact of temporary migration on “the Australian economy, wages and jobs, social cohesion and workplace rights and conditions”. It’s unfortunate – and symptomatic of the disconnects in this area – that this Committee won’t also look at the impact of temporary migration on sending countries, especially in the Pacific. Tongan seasonal workers compete mainly with foreign backpackers, not Australian farm workers.

Between them, let’s hope these inquiries look into what other Pacific countries can do to emulate Tonga’s achievement, and what more Australia can do to make its relationship with the Pacific less about aid and more about mutually beneficial economic opportunities, like the SWP and labour mobility more broadly.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.

Beth Orton

Beth Orton is Manager at the Development Policy Centre. She was previously Senior Research Officer on Devpol’s Pacific labour mobility team. Beth completed a Master of Demography at ANU.