Fred Fisk fought for Australia in the Second World War

Fred Fisk on Pacific reports and consulting in the 1980s. Has anything changed?

By Stephen Howes

7 December 2020

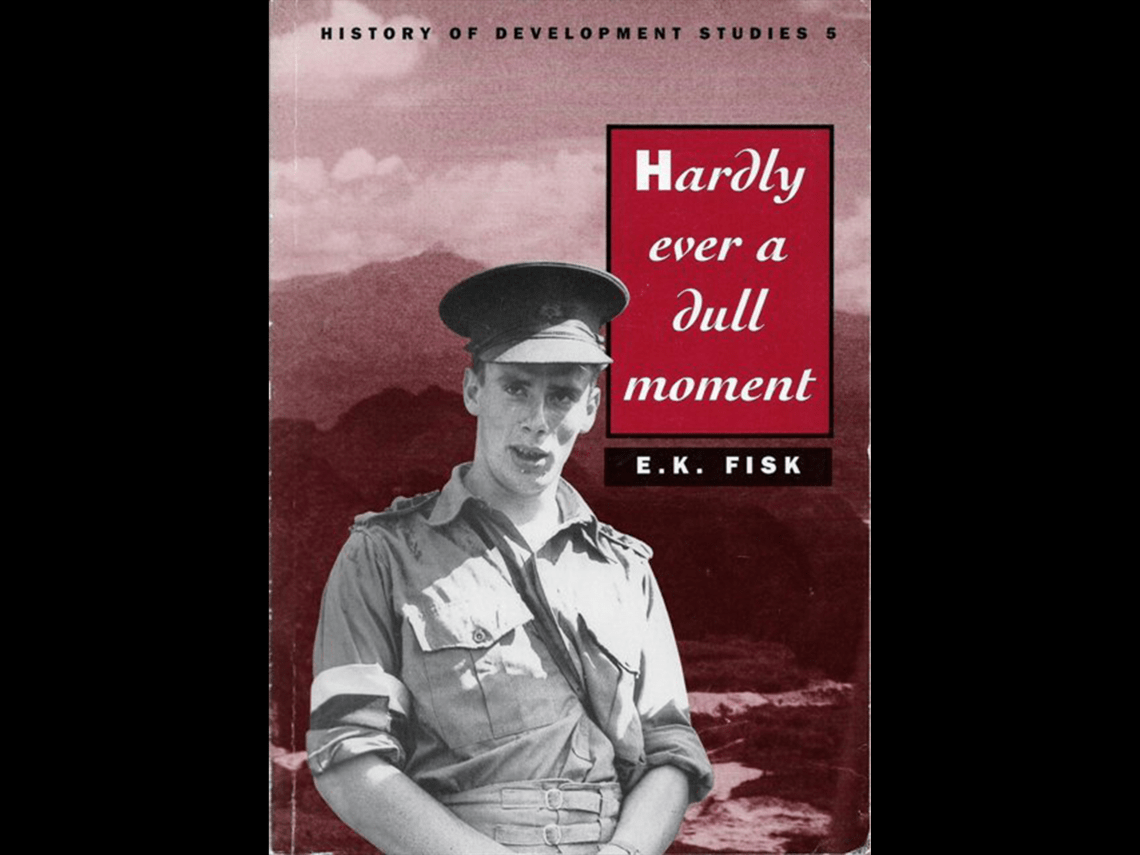

I recently enjoyed reading the memoirs of E.K. (Fred) Fisk, sometimes referred to as ANU’s first development economist, and the person who, based on his PNG work, came up with the idea of “subsistence affluence”. After compulsory retirement aged 65, Fisk turned to consulting in the Pacific. He reviews his experience in the final chapter of his autobiography, Hardly ever a dull moment, an ANU-published book that, like several others, should be online, but isn’t yet.

Reading Fisk’s account from the 1980s, I wondered what has changed…

My new retired status thus did not develop fully until late July 1983, but then the Lord did provide. The Australian Agency for International Development (then the Australian Development Assistance Bureau) decided to set up a special Pacific Team of development officials to increase its capacity for bringing Australian development aid to the island countries of the Pacific. The team was headed by John Wolf, an enthusiastic and experienced aid administrator, who asked me to become a part-time consultant, first to help select and set up the team, and then to work with them as and when my qualifications and experience seemed to be appropriate.

The team selected was an excellent one, and the economist on the team, Colin Mellor proved to be one of the most competent and reliable consultants it had been my pleasure to work with. This led to some very interesting and pleasant assignments around the Pacific, including visits to Tarawa in Kiribati, to Funafuti in Tuvalu, and to the Cook Islands. In all of these assignments I spent some weeks in the country concerned, and then wrote up my reports after returning home, sending them off via modem and MIDAS. I also did numerous minor consultancy tasks for the team, such as commenting on various reports and other documents from time to time.

Many other consultancies came my way from various United Nations institutions and individual countries, so that I was kept pleasantly busy for many years. Of these, one of the most interesting was the preparation of a corporate plan for the Pacific Forum Secretariat, in which I had the pleasure of working with two very congenial colleagues – Tony Hughes, then Governor of the Reserve Bank of Solomon Islands, and S. Siwatibau, who had recently retired from being Governor of the Reserve Bank of Fiji. This was a major undertaking, and involved me in a very interesting tour of a number of the Forum Island countries with Siwatibau prior to our getting together at the Forum Secretariat in Fiji to prepare our detailed recommendations. Another interesting and major task was a survey of the non-monetary subsistence sector in the Forum Island countries. This was a three year task, and involved a detailed examination of the state and function of the non-monetary subsistence sector in Tuvalu, Western Samoa, Kiribati, Solomon Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia, with the help of Professor Gerard Ward, Dr John Connell, Dr Marion Ward and Mr George Kiriau.

The experience of running this particular research program was, however, not all satisfying. It confirmed the doubts that had been developing in my mind about the usefulness of much of the consulting that was going on around the Pacific, including that with which I was personally concerned. It was a common experience in our Pacific travels that, wherever we went, we would run into other ‘expert’ missions also engaged in some consultancy or other. All these missions, including those in which I was involved, would produce large and learned reports to guide the decision-makers in the various countries concerned; but to what effect was increasingly a question in my mind. The sheer volume of these reports was so great that it could hardly be expected that the political decision-makers could find the time to read and digest them, quite apart from the fact that, especially in the very small countries, very few such decision-makers had the training and intellectual preparation necessary to absorb them properly.

As one example, during our field work for the subsistence sector program, George Kiriau identified and collected over 60 recent major research reports from the shelves of Solomon Island government offices. These reports were all dealing with rural and agricultural development policy, were all highly relevant, of high technical quality, and had been completed within the last few years.

Similarly, I was commissioned by two separate UN agencies to write reports on Tuvalu development needs, and having also prepared two other recent reports on much the same subject, I refused. These were, however, prepared by someone else in due course, to what advantage I found it difficult to imagine. It was becoming apparent that these small countries, with their very limited capacity to absorb and use such major intellectual inflows, were being swamped by quantities of specialist advice that they could not put to effective use. I eventually came to the conclusion that it would be improper for me to continue to add to this problem, and that the time had come when I should withdraw from this field of work. In other words, the time had come for another change.

This is an extract from Hardly ever a dull moment by E.K. Fisk published by the ANU National Centre for Development Studies in 1995.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.