Funding to multilateral organisations hits a new high

By Robin Davies

4 June 2015

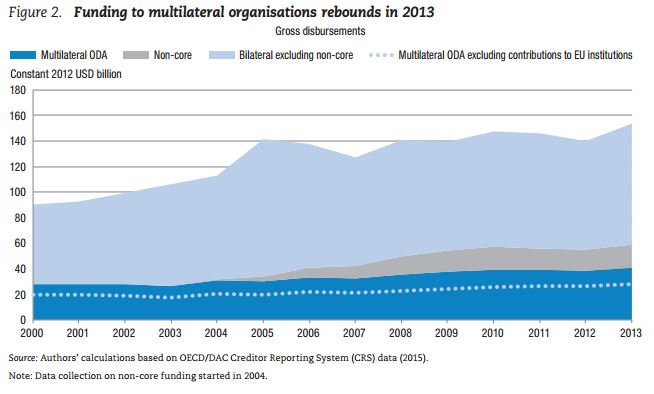

According to new OECD analysis, funding for multilateral organisations from the member countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) reached an all-time high of US$59 billion in 2013, 41 per cent of total Official Development Assistance (ODA). Core funding to multilateral organisations accounted for 28 per cent of total ODA, and earmarked funding 13 per cent. A further US$1.2 billion was provided to multilateral organisations by seven non-DAC providers of concessional finance: Brazil, China, India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

These and other findings are contained in the OECD’s latest multilateral aid report, which is published every two years. While the full report won’t be launched until the UN Financing for Development conference in Addis Ababa in July, a summary version of it was given a soft launch by DAC Chair Erik Solheim during this week’s OECD Forum in Paris.

The figure below, from the summary version, shows 2013 contributions by DAC donor, together with the balance between core and non-core contributions and the ratio of multilateral funding (core and non-core) to total ODA for each donor.

As has long been the case, Australia’s total use of the multilateral system is at the lower end of the range. In addition, Australia continues to be among a handful of donors whose earmarked contributions are around the same size as their core contributions. In fact, in 2013 Australia was the only donor whose non-core funding visibly exceeded its core funding. Australia also distinguished itself by, along with Canada, recording one of the largest decreases in total use of the multilateral system in 2013.

During the soft launch, Solheim said that, for all its well-known problems, the multilateral system has played a central role in delivering some impressive development gains. We should, he said, not lose sight of the fact that elements of the system function very well. However, multilateral organisations needed more and more flexible – that is, less earmarked – support from all countries in a position to provide it, including emerging economies. At the same time, in many cases they needed governance reform, including the retirement of unwritten, anachronistic agreements that see key leadership positions ‘owned’ by various major powers.

The summary report notes that over 60 per cent of funding from DAC countries goes to the European Commission, the World Bank Group and UN funds and programmes, but is not vocal on the problem of multilateral proliferation. (At last count, there were some 230 multilateral organisations, of which fewer than 20 accounted for around 80 per cent of all funding provided.) The report is, however, refreshingly direct about the proliferation of bilateral processes to assess the performance of multilateral organisations:

In 2012-14, 205 assessments of multilateral organisations were carried out by DAC members alone. … To a large degree these bilateral assessments have neither promoted more rational and informed donor allocation decisions nor encouraged better performance by multilateral organisations.

Australia is among the donors that run multilateral organisations through the mill, and is saidto be in the process of ‘strengthening and improving’ its assessment process – though this does not necessarily mean it will become less onerous for the organisations concerned. Given that Australia’s 2015-16 aid budget provided most multilateral organisations with one of only two funding outcomes – you lose 40 per cent, or you lose five per cent – the government could hardly assert any link between assessments and funding allocations.

In a discussion of ‘frontiers in the multilateral landscape’, the summary report remarks on the absence of a ‘policy space’ for discussing strategic, system-wide multilateral issues. While it might be argued that there is in reality no such thing as a multilateral system, or at least no single one, it is clearly correct to say that there is a large need for the member countries of multilateral organisations to reflect on how the most significant organisations could better divide labour or work collaboratively in pursuing global strategies. It’s also the case, though the report does not quite say this, that the major donors to multilateral organisation, funds and programs ought occasionally to consider in a more holistic way how to allocate their resources over a given period of time, rather than taking their decisions one funding drive at a time.

The necessary policy space for discussion of such matters would most logically be provided by the G20 but, aside from its unhappy experience with IMF quota reform, that body has so far done little with respect to multilateral reform and has barely ventured into the realm of cross-institutional strategy and governance.

About the author/s

Robin Davies

Robin Davies is an Honorary Professor at the ANU’s Crawford School of Public Policy and an editor of the Devpolicy Blog. He headed the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security and later the Global Health Division at Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) from 2017 until early 2023 and worked in senior roles at AusAID until 2012, with postings in Paris and Jakarta. From 2013 to 2017, he was the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre.