Market place at Kiunga, 24 March 2020, after COVID-19 ‘awareness’ by police (Credit: Senior Shintaro Dumo)

God, health and COVID-19 in remote Papua New Guinea

By Monica Minnegal and Peter Dwyer

16 April 2020

The first COVID-19 case reached Papua New Guinea (PNG) on 13 March 2020, though it was several days before it was unambiguously confirmed. On 17 March the pandemic was declared a national security issue, and a State of Emergency came into effect on 24 March.

By coincidence, in the week commencing Monday 16 March, members of one group of landowner beneficiaries associated with the multibillion dollar PNG Liquified Natural Gas project were arriving in the Western Province town of Kiunga. They expected to finalize arrangements with officers of the Department of Petroleum and the Mineral Resource Development Company (MRDC) for the receipt of royalty payments. These payments had been held up for more than five years. The group included people, or the descendants of people, we have known since 1986. Some of them now lived in Kiunga. Some had come by air or by foot from their home village 110 kilometres to the east. Others had come from Port Moresby, the capital city of PNG.

One of the Port Moresby men – we shall call him Jacko – was employed by MRDC as a liaison officer. He was a landowner who had relocated from his home village to Port Moresby in the late 2000s as the LNG project became a reality and many people patterned their lives around an expectation of imminent royalty payments. In Port Moresby, Jacko acquired competence in English, in reading and in both accessing and using digital resources: mobile phone, email, WhatsApp, Facebook, the internet. At best, people in his home village had access only to mobile phone connection, with even this, far from reliable. Jacko lived in and accessed the outside world in ways that were impossible for most of his kin. His learning, and his messages, influenced their understandings.

Kiunga became quiet. Airlines throughout PNG were grounded. Port Moresby residents were now stranded in Kiunga, and Jacko filled his hours exploring the web and posting to Facebook. Late in the morning on 24 March he posted a simple message: ‘PNG people will not be impacted by Corona virus disease’.

We were concerned that this might be the sort of message he would convey to the village people we knew. Though we seldom do this, we intervened. We wrote:

“Jacko. That is wrong. That is dangerous advice. If you love your friends and family, take this post down. You are spreading false information. People must follow the advice of the PNG health department to help prevent the spread of this dangerous virus that is killing people all over the world.”

Jacko replied:

“Yes, we can advise our PNG People to take extra precautions measure to follow WHO advise from spreading the virus. Bottom line is PNG Christian country which God had placed in the center of the equator where it is consistent with a temperature of up to 26-27 degree Celsius.”

Jacko tells us that God placed the Christian country of PNG at the equator where moderately high temperatures would protect the people from the ravages of the virus. He agrees, however, that it would be sensible to take extra precautions with respect to hygiene.

Jacko then began to reinforce his message. In posts on both 24 and 25 March, ‘COVID’ was decoded as ‘Christ Over Viruses & Infectious Diseases’ and ‘19’ was taken to refer to the biblical verse found at Joshua 1:9: ‘Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous. Do not be frightened, and do not be dismayed, for the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.’

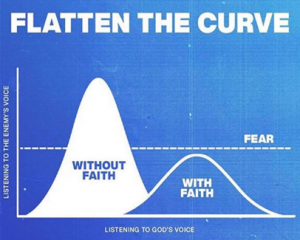

A search within Facebook suggests several likely sources; a good candidate is the African-focussed missionary site ‘Heaven At Last-Godgift’ which used one of the images reposted by Jacko. Others that make use of the same ‘translation’ of ‘COVID’ include Redwood City SDA Church which shows graphically how the virus disease curve may be flattened, and fear reduced, by faith.

On 25 March, as well, Jacko reposted a statement by a graduate of the University of Papua New Guinea. That man had confidence that ‘COVID 19 wasn’t meant for us PNGeans’. He commented that Papua New Guineans had been back and forth to China but the virus had not rapidly entered PNG. He told his Facebook followers to, ‘have faith that we can overcome this COVID 19 pandemic with our All Mighty King…Lord Jesus Christ’.

Clearly, our small intervention failed to shift Jacko’s understandings. Indeed, we may have reinforced them. We should have known better.

Jacko had nothing against hygiene or any other precautionary measures suggested by people with knowledge and authority. Those measures were party to a secular system that had much to offer to the wellbeing and happiness of people. But Jacko understood also that the wellbeing and happiness of people were contingent on their appreciation and acceptance of the sacred. He may have prioritized the sacred but he gave recognition to both. The wording of our intervention prioritized the secular without granting recognition to spiritual dimensions.

Yet we had been there before. Thirty-three years earlier, on the bank of the Strickland River, we lived with 25 people at the village of Gwaimasi. We often saw, or from neighbouring communities heard about, sick people. Some were very sick. In several cases a curing dance was held. One or two costumed men would dance through the night to the beat of a kundu drum, brushing their sago-frond skirts across the body of the sitting invalid, and drawing the attention of spirits who might come to their aid. The next morning the sick person might be carried to the mission station – a two-day walk through swamp and rainforest – for treatment by the resident expatriate missionaries or the national community health worker. It was necessary to be careful in only one detail. Community health workers should not be told that a curing ritual had been performed because, if they learned this had happened, some refused to provide treatment; they saw appeal to customary spirits as challenging their secular expertise.

In the 1980s, people at Gwaimasi were willing to draw on both the secular and sacred in seeking the best health outcome for those whom they loved. There seemed little point in accepting the apparent benefits of modern medicine if one’s spiritual being was out of kilter. And, ultimately, though he prioritized the latter, Jacko was acting as his own people had done more than three decades earlier. He was saying that it was worth attending to both systems of wellbeing. It should not be thought that this approach is peculiar to PNG. One of us enjoyed the same experience as a child. When a sibling was ill, her triple-certificated nurse mother took full advantage of both professional medical advice and the local priest blessing the house by sprinkling Lourdes water.

When Jacko’s messages reach his home village, and they will, we hope there is balance in the way they are received. Remote areas of PNG may be sufficiently isolated that the risk of COVID-19 arriving is low. But customary practices with respect to physical distance within communities, and inadequate health facilities, means that they will be far from ideal places if the virus does arrive. Far from ideal because in an emergency of this nature, and in places such as this, the state is not equipped to provide any assistance.

Vaccination, health facilities and customary social distance among Kubo people, 2014 (Credit: Peter Dwyer)

This post is part of the #COVID-19 and the Pacific series. See a response to this article here.

About the author/s

Monica Minnegal

Monica Minnegal is an Associate Professor in the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Melbourne.

Peter Dwyer

Peter Dwyer is an Honorary Senior Fellow in the School of Geography at the University of Melbourne.