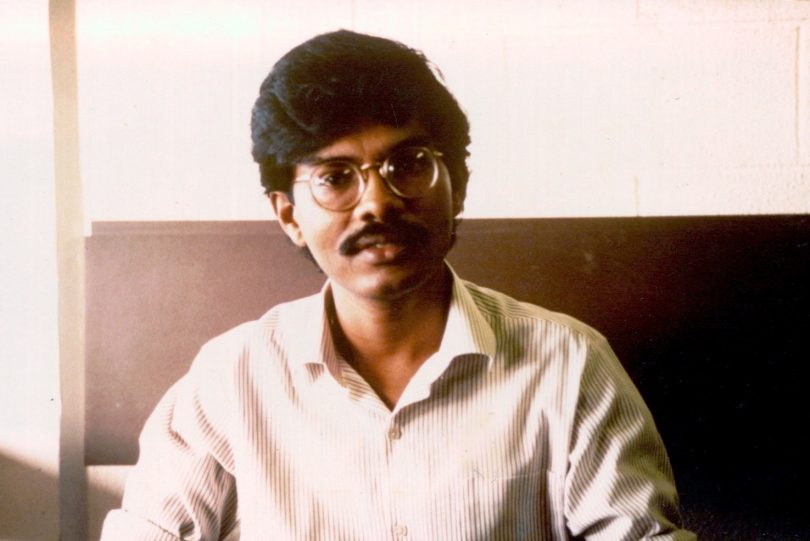

Brij did not just write Fiji’s history. He was part of it. We have already heard about the part he played as a commissioner in the 1996 Fiji Constitution Review Commission. In 2009, Brij became the icon of a darker chapter in the history of our country – arrested, assaulted, threatened, deported, banned from entering Fiji, and repeatedly criticised and condemned by the Fiji government. His treatment became a political issue in its own right.

These were the actions of our own government. Few, if any, of us here at this memorial service chose that government. Indeed, in 2006 some in this government picked up guns and chose themselves.

But we have acquiesced in it, we pay our taxes to it, and whether we like it or not, it speaks for us in the wider world. And, even though it was Brij and his wife Padma who bore the burden of this government’s actions against them, those actions continue to diminish and cheapen all of us.

But that is the exact opposite of the books Brij wrote. To read a beautiful, well-crafted book about Fiji, to recognise the places and the stories, is a source of pride for all of us.

Fred Wesley wrote an editorial in Tuesday’s Fiji Times about it. “Professor Lal”, he said, “epitomised the value Fijians have for their connection to their homeland. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are reminded about this sense of appreciation and value. We are reminded about who we are – Fijians!”

Long after dictators and politicians consumed by pettiness have gone – consigned, as they say, to the dustbin of history – real history lives on. And that is only one of the legacies Brij has left us.

I am guessing that many of us here, on hearing the news of Brij’s death, picked up one of the many books he had written and which sit on our shelves. My choice was Mr Tulsi’s Store. Many of you know this collection of personal stories, ranging from Brij’s childhood in Tabia to his travels in India and Fiji, and his life lived in between.

Brij’s grandfather, like mine, was a Girmitiya. His grandfather served his indenture in Labasa, as did mine. His grandfather remained in Vanua Levu; mine moved to Lautoka. Brij was his grandfather’s favourite child (or so he said); I never knew my grandfather, who returned to India in his old age and died there when I was three.

Brij’s great talent, it seemed to me, was to make history come alive. Sterile academic writing is the day job of the historian. Facts and analysis are what historians do. Those are what we expect to read when we pick up a history book – but we hope at least that the writing will be fluid and fast-moving.

And in a lesser historian, this kind of work might be enough to create a respectable career, and a justification, as they say, to rest on one’s laurels.

History might have been Brij’s day job. If you pick up today’s [30 December 2021] Fiji Times and turn to page 35 you will read an astonishing range of tributes to him, from all over the world – Australia, France, Guyana, India, the Netherlands, South Africa, Surinam, Trinidad, the United Kingdom, as well as Fiji – a page of them. Those tributes are worth reading by themselves. What a career, what a legacy to leave behind.

Pick up and read his biographies of A.D. Patel and Jai Ram Reddy. Enjoy not just the history – which is history about us – but also enjoy the fluency and pace with which these books are written.

But as we all know, Brij wrote much more than academic history. When he was writing about Fiji, he wrote with a passion and humanity that defied academic discipline. He made our history human and readable and accessible, which is so important. Writing well is so important. Because what is the use of writing history if no one is going to read it?

In the preface to his book Broken Waves, this is what Brij says:

In this account I make no special effort to invoke an impartiality I do not feel. When embarking on a comprehensive examination of the contemporary history of one’s own country, it is impossible to be detached unless, in the words of Professor O.H.K Spate, one is a “moral and intellectual eunuch”. Who would want to be that?

And now he is gone. So who will write our history now?

We can treat that question as a lament, or a challenge. I would prefer it to be a challenge, to all of us. We have to write.

We cannot all write as Brij did – indeed very few of us will ever do that. But we have to write things down, record our experiences, and make our own histories accessible to others.

Some of that writing will be sober, objective and professional. Some of it will be passionate and from the heart. Some of it will be good; some of it, no doubt, will be terrible. But most of us, with a little careful thought, organisation and diligent editing, can write. We cannot all be eminent historians. But we can all be historical sources.

One day, the current chapter in our political history, which began with a so-called “clean up campaign”, will end. And then we will be left to do the real cleaning up. Only then can Fiji be a better country. Only then can we realise the ambitions that those like Brij have for all of us.

We have huge obstacles to overcome. We are a country racked by increasing poverty, apathy, and mistrust in the good that governments can do. How can we persuade people who are preoccupied simply with survival that democracy, good governance and rule of law are so important to make Fiji better?

One answer to that question is history. History beats dry books on law and public administration. History that is relatable, recognisable from shared experiences, teaching us lessons about things that we must learn not to repeat, and offering us stories to which we can aspire. To tell us what an ombudsman does – or, at least, in Fiji, what an ombudsman used to do.

That is why the solid foundations that Brij has left us, in his scholarship and his story-telling, are so important. They belong not to the past but to the future. And it is now for all of us, if we care enough for Professor Brij Lal’s memory, to build on those same foundations.

This is an edited version of the author’s address at a memorial gathering for the late Professor Brij Lal in Suva on 30 December 2021. This is the fourth of a series of tributes to him, collated at #Brij Lal.

Namastey Sir

I came to know that in Fiji and other parts of the world, there are people belonging to Ballia district, whose ancestors had gone there as indentured laborers.

Do you know any such person, whose ancestors were residents of Ballia?

“ How can we persuade people who are preoccupied simply with survival that democracy, good governance and rule of law are so important to make Fiji better?”

This question goes to the heart of difficulty many of us have trying to convince our people that broader institutional issues matter, in the long run.