Human-centred solutions to the refugee education crisis

By Thomas Brown

27 July 2017

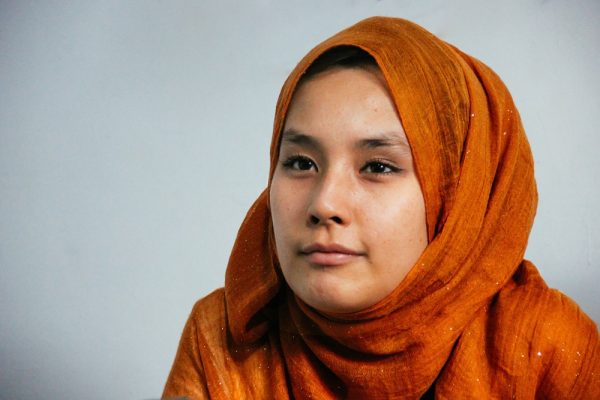

Madiha Ali, a bubbly 16-year-old from Pakistan, speaks animatedly in fluent English. She talks of her ambitions to become a writer or businesswoman, and how she misses being a student. Forced to give up her own education when her family fled to seek asylum in Indonesia three years ago, she has no prospect of continuing her study here, and has instead turned her focus to helping others by becoming a teacher. She is part of a small but dedicated group of refugees who have established an education centre in the rolling mountains of West Java, to serve the needs of their community.

There are currently 3.7 million refugee children out of school globally. As Western countries continue to stall on finding meaningful solutions to the global refugee crisis, more refugees are being forced to spend long periods of time in host countries with poor protection frameworks and limited resources. Developing countries host 86% of the world’s refugees, and while they have escaped immediate danger, their basic human rights and economic, social, and psychological needs can remain unfulfilled. With refugee education in crisis, there are calls for innovative solutions to address basic service delivery gaps, as the old models of humanitarian assistance become increasingly ineffective.

Asylum seekers like Madiha who have sought protection in Indonesia have no access to employment, education or health subsidies during their stay. Indonesia is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, and offers no pathways for refugees to settle in the country. Instead, refugees live for some years in a state of limbo as they await resettlement through the UNHCR to a country that will accept them. Faced with the prospect of children missing years of education at a critical stage of their development, groups of refugees living in West Java have independently initiated a number of education centres, which now serve up to two hundred children. Refugees contribute their skills and expertise to fill different roles as administrators, managers and teachers to run the centres.

While these facilities provide vital education to children, they also support a range of additional activities and can be seen to benefit the refugee community at large. The centres serve as makeshift community hubs, and support English classes for adults, sports programmes, community-based health workshops, vocation skill-sharing programmes and arts and handicraft classes for women.

More than we realise, refugees all over the world initiate their own informal organisations to address the needs of their community. These ‘refugee-led initiatives’ mobilise the significant human capital of the refugee community, which so often goes untapped in international humanitarian efforts intended to assist refugees. They are prime examples of human-centred design, serving to both empower refugees by making use of their skills and experiences, while also delivering sorely needed services to the refugee community in a responsive and cost-effective way. Incorporating refugee-led organisations into development programmes has great potential, and some NGOs have recognised this, supporting refugees and developing their capacity so they can provide sustainable solutions to the problems facing their communities.

Swiss/Australian NGO Same Skies began working with refugee groups on education initiatives in Indonesia in 2014. Same Skies sends expert volunteers on field visits to conduct capacity-building workshops, including teacher training, child protection, financial management and first aid. They help with some startup financing initially, but provide guidance on marketing and fundraising to the staff in order for the centres to become independent and self-sufficient. This is supplemented with regular video-link meetings to provide guidance and support remotely on issues as they arise. After two years of support, they turn the programmes over fully to the refugee community.

French group Urban Refugees takes a broader approach, identifying pre-existing refugee-led organisations doing good work in cities all over the developing world, and partnering with them to increase their capacity and credibility. They deliver six-month ‘incubator’ programs to the leaders of refugee organisations, providing them with the tools to ensure their long-term autonomy and sustainability.

Some large organisations such as UNHCR are also getting behind this concept. In Malaysia, the UNHCR runs a Social Protection Fund initiative, which supports a range of small-scale self-help projects developed and implemented by refugee groups. The program has since supported 320 projects including income-generation projects, skills-training programmes, and community service initiatives like community centres, sports and recreation halls as well as day-care and shelter services.

Supporting refugee-led organisations in this way represents a shift in thinking away from the classic top-down approach commonly found when responding to crises. Rather than designing programs for, or even with refugee communities, these are human-centred solutions designed and implemented by refugee communities with external support. After all, refugees know best the needs of their community and in most cases have the skills and experience needed to serve them.

Supporting refugees to identify and design their own solutions ultimately represents a more efficient, cost-effective and sustainable approach to refugee assistance, and can help to create empowered, self-sustainable refugee communities.

Thomas Brown is a researcher on forced migration in Indonesia and the Monitoring and Evaluation Coordinator for refugee NGO Same Skies.

About the author/s

Thomas Brown

Thomas Brown has spent the last two years researching refugee issues in Indonesia. He is also the Monitoring and Evaluation Coordinator for Swiss-Australian NGO Same Skies, and on the Executive Committee of the Jakarta Development Network. He is the recipient of the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) Euan Crone Asian Awareness Scholarship.