MDGs and gender in the Pacific: have we achieved anything?

By Priya Chattier

8 September 2014

Global debates about the Post-2015 Development Agenda are in high gear. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2014 was recently released in New York City with an accompanying Australian launch at ANU. The UN has also released its draft of what the post-2015 framework will probably look like. With so much debate and discussion it is easy to lose sight of the wood for the trees. Here I ask what that wood might look like from a Pacific perspective on gender equality and women’s human rights. I will examine what lessons can be learned from the decade or so of implementation of the MDGs.

Although many commitments have been made by the Forum Leaders’ Gender Equality Declaration [pdf], progress on gender equality in the Pacific has been poor. Gender inequality remains a significant development challenge for the countries in the Pacific. Nations are unable to reach their full potential when half of their citizens are excluded from important leadership and economic opportunities.

According to the 2013 Pacific Regional MDGs Tracking Report [pdf], women continue to be more likely to live in poverty than men. The Toward Gender Equality in East Asia and the Pacific report by the World Bank shows that women in the Pacific are over-represented in poor households because they are less likely to have paid work and their average pay is lower than men. For instance, the World Bank’s 2012 World Development Report shows that in PNG, according to the 2009 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, 59 per cent of women and 53 per cent of men reported selling subsistence products, but men reported earnings twice as high as women’s. Women’s lack of productive resources and their ‘time poverty’ [pdf] also contribute to their relatively high poverty rates in the region. Women do the vast bulk of unpaid household work and are the main providers of care to children, the elderly and the sick. Heavy domestic and childcare responsibilities either hinder women from entering or maintaining formal, waged labour or restrict women to low-paid jobs.

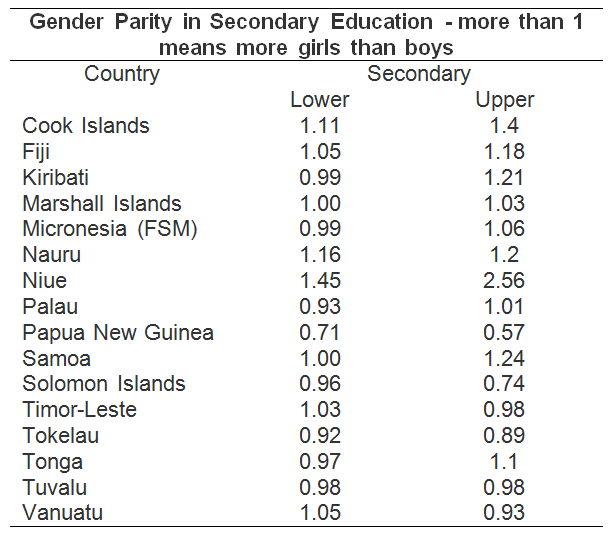

Although gender equality in access to primary schooling has almost been achieved in most countries in the region, there are still some countries like Papua New Guinea where the disparity remains significant. Generally, progress in Oceania has been made in getting more girls in school and getting them to stay longer. The Gender Parity Index for most countries is above 1 in secondary education.

Source: UNESCAP Statistical Yearbook 2012 (based on Gross enrollment ratios)

Source: UNESCAP Statistical Yearbook 2012 (based on Gross enrollment ratios)

The UN HLP report [pdf] states that if girls are kept in school to complete a quality secondary education, they will be much better equipped to reach their full potential and make informed choices about their lives Just one additional year of school would give women much better economic prospects and more decision making autonomy. Staying in school, however, is another matter for boys. The 2012 Forum Education Ministers’ meeting noted an emerging trend across the region for more boys than girls to drop out of secondary education. The reasons are not yet well understood but may be connected with rising poverty levels and pressure to earn a living, together with a lack of vocational options. Both Samoa and Fiji are noting a tendency for girls to perform better than boys at secondary school.

While more women in the Pacific have entered the workforce in recent decades, they typically work at the informal end of labour markets with poor earnings and insecure conditions. Women’s labour force participation rates [pdf] in the region are low, with significant disparity recorded in Solomon Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) and Samoa where men’s participation rate is almost double that of women’s. Legal and other barriers to economic empowerment are common. Unequal pay for comparable work, sometimes even lower statutory minimum wages, and poor working conditions, including violation of women’s sexual and reproductive rights and violence against women, are rife among informal women workers in both organised and unorganised sectors of enterprises. Labour market surveys by the International Finance Corporation show that women still face a gender pay gap, segregation in occupations and glass ceilings, with over-representation in low-paying jobs and under-representation in senior positions.

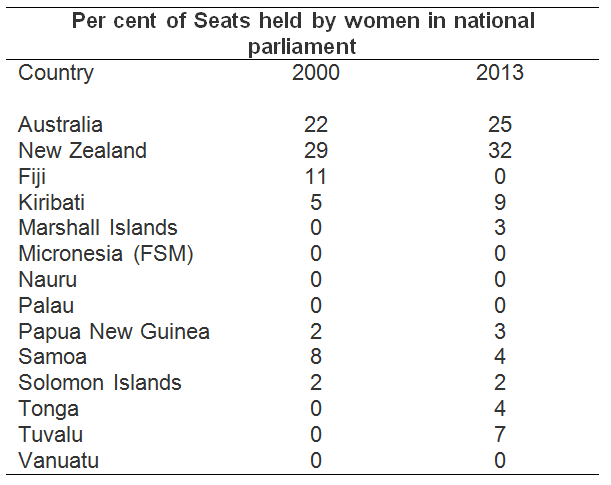

Women’s capacity to participate in and influence the decisions that affect their lives–from the household to the highest levels of political decision making–is a basic human right. Yet, women’s political representation in Pacific parliaments remains the lowest in the world. The Pacific compares poorly with the world average of 22%. Efforts have already been made to support women candidates and to provide training in a range of areas including political campaigning. But this has not been enough to address the paucity of women represented in local and national political structures.

Samoa is the only PIC that has legislated Temporary Special Measures to promote gender balance in national legislatures. At the sub-national level, there is also progress. Tuvalu has passed a law requiring female representatives on local councils, and Samoa has initiated a programme to appoint a woman representative in every village council. In 2013, the Parliament of Vanuatu passed legislation amending the Municipalities Act, such that one seat in every ward must be held by a woman.

Source: International Parliamentary Union, 2013

Source: International Parliamentary Union, 2013

Despite progress in some areas, gender equality and women’s empowerment remain “unfinished business” in the Pacific region. The primary focus of the MDG targets for gender equality was on social development. While this directed welcome attention towards improving women and girls’ health and education, women’s roles in and contributions to the economy were largely ignored. Gender gaps still remain in women’s economic and political opportunities. The roots of deprivation and inequality lie in power relations that cut across multiple aspects of people’s lives.

The post-2015 framework presents a unique opportunity for the Pacific to build on the achievements of the MDGs, while also addressing the dimensions that lag behind. The sustainable development framework beyond 2015 offers some hope for the Pacific region with its holistic approach to addressing gender inequality through tackling discriminatory social norms and practices that impede progress towards gender equality. In fact, the post-2015 framework retains a strong, stand-alone goal on gender equality and women’s empowerment but also includes gender-specific targets and indicators in the other 16 goals. It will be interesting to see whether or not and how the Pacific Women Shaping Pacific Development initiative will help accelerate the Post-2015 Development Agenda with $320 million committed over 10 years in support of gender equality in the Pacific region.

Priya Chattier is a Pacific Research Fellow at the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program, ANU.

About the author/s

Priya Chattier

Priya Chattier is a Pacific Research Fellow at the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program, ANU.