Doris Talban, 51 (maybe older?). Affording and accessing clean water is a struggle for Doris. Marata 2 settlement, Port Morseby, Papua New Guinea.

Pacific countries still struggling to provide access to safe water

By Luke Lovell and Tom Muller

22 March 2016

Today is World Water Day – a day dedicated to one of the most precious resources on earth. It’s a day to reflect on the importance of water, but also to take action to move towards a world in which safe, sufficient and reliable water supplies are available to every person.

As World Bank President Jim Yong Kim has recently noted, achieving universal access to water, ‘would have multiple benefits, including laying the foundations for food and energy security, sustainable urbanisation, and ultimately climate security.’ However, at a time when threats to water supply – droughts, floods, water pollution and unsustainable use – are growing, so does the challenge of increasing access to safe water. With four billion people experiencing water scarcity at least one month of the year, there are warning signs of a looming crisis which poses serious threat to sustainable development.

Closer to home, the interlinked challenges of ensuring universal access to safe water while sustainably managing water supplies are being wrestled with in the Pacific. At 56 per cent of the Pacific population [pdf], water coverage is lower than in any other region. These figures are skewed by the size of the population, and the size of the problem, in Papua New Guinea. Only 40 per cent of people in PNG have access to an improved water source, with Kiribati the next lowest at 67 per cent [pdf]. Given that PNG is home to 75 percent of the regional population, the country drags down regional averages. Across the rest of the Pacific, ensuring equitable access is the primary challenge, as is the case for Vanuatu.

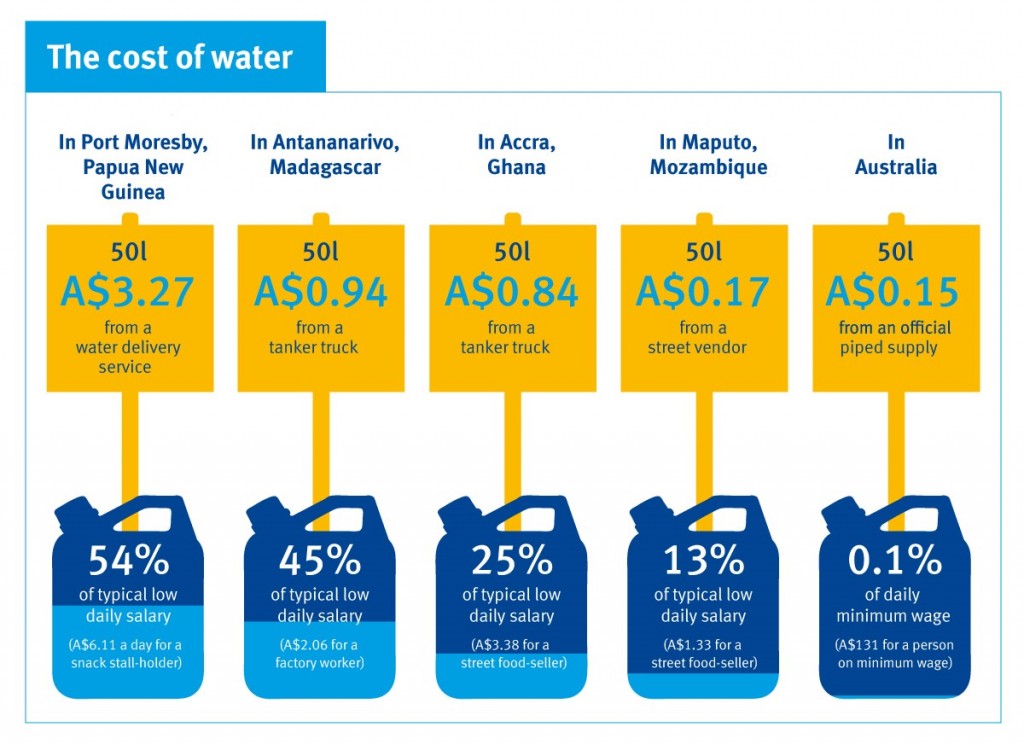

WaterAid’s new global report Water: At What Cost? The State of the World’s Water [pdf], reveals the high price Papua New Guineans are paying for this most basic need in the absence of public water supplies. PNG is not only the country with the highest proportion of people without access to water, but is also one of the most expensive places to purchase water.

Few of Port Moresby’s informal settlements, where roughly half of the capital’s population reside, are connected to public water mains and sewerage pipes. This leaves people to purchase water for drinking and cooking from private vendors. At a cost of 7.5 PNG Kina ($3.25AUD) for 50 litres (the World Health Organization’s recommended minimum to meet daily basic needs) a low-income earner in PNG can expect to spend up to 54 per cent of their daily earnings on clean water [pdf]. People that can’t afford this price are left with a wicked choice: restrict their water use to potentially unsafe levels, or collect dirty water from groundwater sources such as ponds and rivers.

There are numerous reasons for low access and high cost. As DFAT Secretary Peter Varghese highlighted at the Australasian Aid Conference in February this year, ‘[t]he context in the Pacific is very different. Pacific Island States have specific challenges because of their size, geographical dispersion, remoteness from markets and higher risk of natural disasters. …This provides us with a different set of challenges than in growing Asia. And it means that we need to entertain different options and ways of engaging.’

In PNG, water supply has been given relatively low domestic political priority and in turn received limited financial investment; responsibilities for services are fragmented, with limited coordination between actors; sector capacity is low, across management, operations and maintenance and monitoring; service delivery cost is high due to small, remote populations and geographic challenges; and informal settlements are growing rapidly, with legal, technical and financial barriers to service provision within them slowing the rolling out of services [pdf]. All of these challenges are exacerbated by the potential impacts of climate change. The El Nino-related frosts and droughts of 2015 are estimated to have impacted more than 1.8 million people, as crops are destroyed and drinking-water supplies run short.

If PNG is to make significant strides in improving access to safe water, and other Pacific nations are to improve equity of access, it is clear things need to change.

Australia can make a significant contribution to support PNG and the rest of the Pacific to drive change by increasing investment in national and regional water supply strategies and capacity, while prioritising approaches that target the poorest and most vulnerable – women and girls, people with disabilities, older people and those living in informal and remote settlements.

To do this the Government needs to chart a new course to progressively restore the $66.7 million cut made to the aid budget for basic water and sanitation in Asia and the Pacific for FY 2015-16.

In developing different options for the Pacific, the Australian Government should also use its climate financing – $200 million per year for the next five years – to enhance the water security of the most vulnerable Pacific people and communities. This should include strategically investing in the capacity of Pacific countries to apply for, absorb and leverage global climate change funds to address water security needs.

Continuing to under-invest will have serious consequences. Failing to prioritise people’s access to water in the Pacific will only undermine the region’s potential for sustainable development.

Luke Lovell is a Policy Officer and Tom Muller is Director of Policy and Campaigns at WaterAid Australia.

About the author/s

Luke Lovell

Tom Muller