(Credit: Laurissa Smith/ABC)

Pacific Labour Scheme: beefing up Australia’s meat industry

By Holly Lawton

21 February 2020

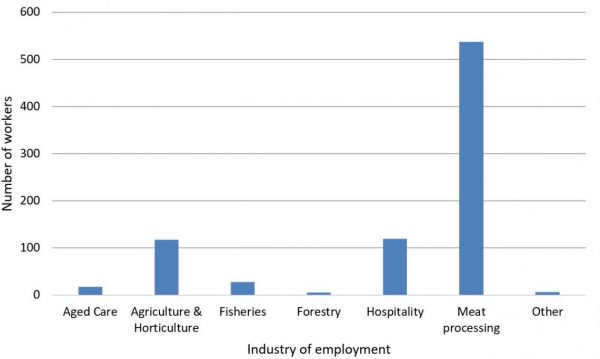

The Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) is designed to help meet domestic labour shortages in rural and regional Australia. At the end of January a total of 830 PLS workers were in Australia in seven key industries. But there’s one industry that’s dominating – 65 per cent of all PLS workers are engaged in the meat processing industry.

PLS representation in the meat industry is spread across five states, with the majority of workers in New South Wales (44 per cent) and Queensland (20 per cent).

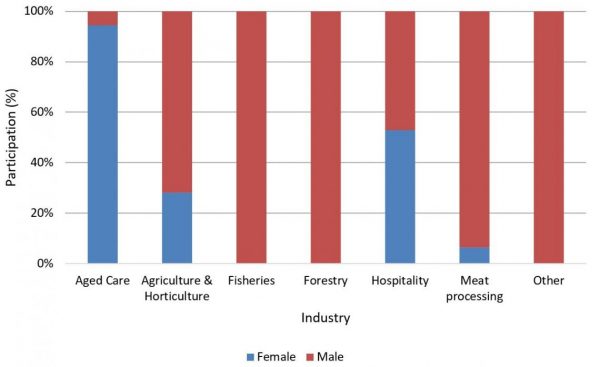

It is heavily gendered. Only 7 per cent of meat workers currently in Australia are female. This contrasts starkly to the 39 per cent female participation in the scheme outside of the meat processing industry. As a result, the overall PLS female participation rate is 17.8 per cent, very similar to that of the Seasonal Worker Programme (17.9 per cent in 2018–19).

PLS workers by industry and gender

Only seven PLS workers were employed in the industry in late July 2019. There are now 537, which means 85 per cent of total growth in the scheme between July 2019 and January 2020 has been in meat workers.

It is not that growth outside the meat industry has been slow: it’s about 50 per cent. But what explains the phenomenal 7,571 per cent growth in meat processing workers?

The meat industry has long relied on migrant workers to meet its workforce needs. One PLS employer in the industry recently reported that 80 per cent of his workforce were either backpackers or visa workers and that, “Attracting staff has become a major issue for the meat processing sector and affects the ability to fill orders and throughput.” This is not unique to the meat industry though as similar reports from the horticulture, hospitality/tourism, and other industries have shown. What is different about meat?

One clue is the extent to which the industry is the subject of special migration agreements. The Meat Industry Labour Agreement goes back to 2011. It facilitates recruitment of skilled overseas meat workers either on a Temporary Skills Shortage visa (subclass 482) or Employer Nomination Scheme visa (subclass 186). Candidates need to be able to demonstrate previous experience at a recognised meat processing plant or be assessed. There are currently 40 active employment-specific labour agreements (a prerequisite to reap the benefits of the industry agreement) for the meat industry, some of them, presumably, held by PLS approved employers.

Designated Area Migration Agreements (DAMA) provide another route for offshore hiring of workers. Warrnambool is home to 35 PLS meat workers. It may not be the area with the highest number of PLS meat workers (Wagga Wagga and Tamworth currently vie for that title), but it’s an interesting case study as, unlike other regions, it also benefits from being party to a DAMA. Effective from March 2019, the Great South Coast DAMA includes provision for 27 occupations, including a number of semi-skilled (ANZSCO 4 and 5) meat processing related occupations, including meat boner and slicer, and slaughterer. Employers enter into a labour agreement with the government and gain access to occupations not available through other subclass 482 visa streams.

Both streams have stringent English language requirements.

Why, when they have these alternatives, are employers turning to the PLS? First, it’s a very flexible mechanism, with the only requirement being that the occupations for which workers are being recruited fit into ANZSCO level 3 to 5 skill bands, and roles are unable to be filled domestically. Workers don’t always need specific skills or experience and English language requirements are more relaxed.

Second, it’s cheaper. The base application charge for employers for the PLS is $310. It’s $2,645 for a subclass 482 visa. Add to that the DAMA fee for endorsement ($600–$900), Skilling Australians Fund Levy ($1,200–$1,800/year/worker to support workforce training for locals), and the cost of sponsoring ($420) and nominating ($330/worker), subclass 482 visas and the costs start to add up.

Third, the PLS is also well supported. The DFAT-funded Pacific Labour Facility shepherds employers through compliance for PLS approved employer status, helps to facilitate connections with prospective employees in the Pacific, and provides welfare support to workers when they mobilise. Other labour agreements are not nearly as well resourced.

In summary, one might say that the PLS struggles to compete against migrants already in Australia and looking for work (backpackers, students, spouses). But, where those migrants are not willing to work in the sector concerned, the PLS competes well against other mechanisms for offshore recruitment of low- or semi-skilled labour.

One interesting feature is that both the DAMA and the Meat Industry Labour Agreement offer a pathway to permanent residence. (They also both allow families to accompany workers, unlike the PLS.) Will we see Pacific workers arrive under the PLS and then transition to another agreement? By the time their three years on the PLS is up, the workers might well have the skills and English to qualify, and, if they have proved themselves, their employers might be willing to cover the costs of helping them switch.

About the author/s

Holly Lawton

Holly Lawton worked as a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre, with a focus on Pacific labour mobility. She holds a Master of Development Practice from The University of Queensland.