Family compound in Vanuatu, including an RSE house with solar and a satellite dish

Participation in the RSE scheme: the myth of opportunity

By Charlotte Bedford, Heather Nunns and Richard Bedford

20 October 2020

This is the fourth in a series of blogs outlining key findings from the Impact Study of New Zealand’s Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme. The Study, involving more than 480 research participants, examined some of the RSE scheme’s social and economic impacts in six New Zealand communities and in five participating Pacific countries.

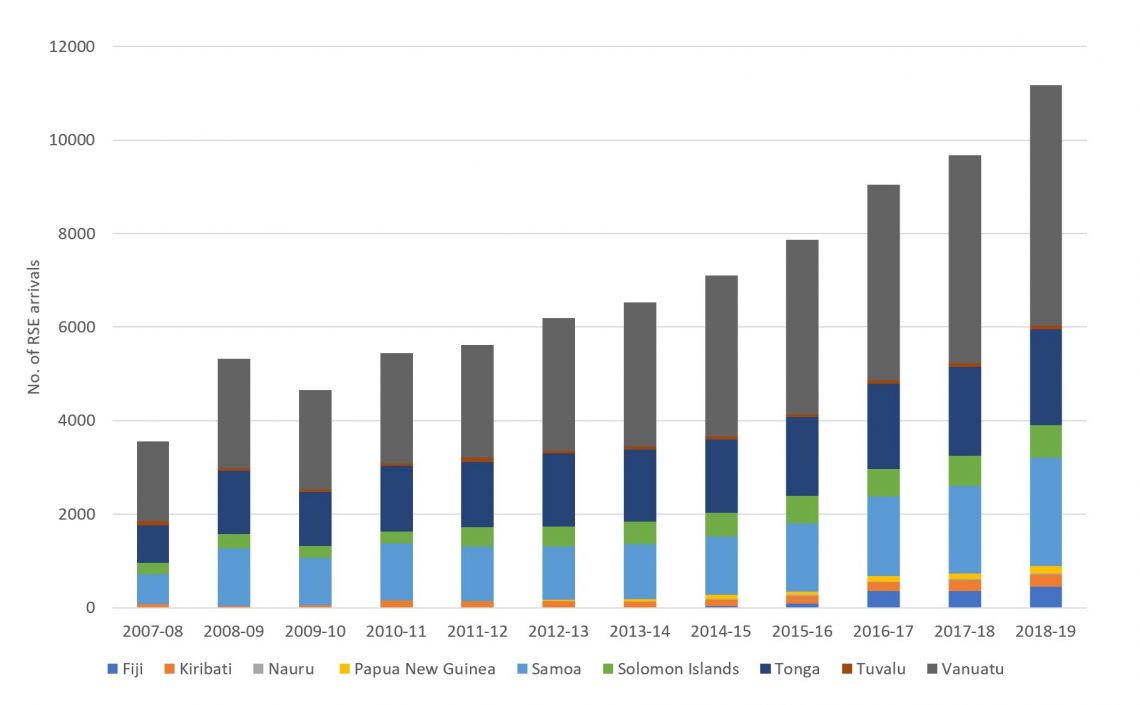

New Zealand’s RSE scheme brings in seasonal labour, mainly from the Pacific, and provides an essential supply of seasonal workers to the country’s export-driven horticulture industry. From relatively small beginnings involving around 4,500 workers in 2007/08 (Figure 1), the RSE scheme has steadily grown subject to increases in the national cap on RSE numbers, and in line with widespread expansion of the horticulture and viticulture industries.

This expansion has largely been driven by RSE employers’ access to a consistent supply of RSE labour. In October 2019, the annual cap was raised to 14,400 workers and has been kept at that level for the 2020/21 season.

Figure 1: Total RSE arrivals, 2007-2019

Since the scheme’s implementation in 2007, distribution of RSE workers across participating Pacific countries has been uneven. Three Pacific countries – Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa – have dominated RSE labour supply.

Access to RSE work: a level playing field?

At the time of the RSE scheme’s introduction, five Pacific countries – Kiribati, Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu – were granted preferential access and were provided with facilitation measures to support their participation. The measures were designed to help create a ‘level playing field’ for Pacific countries to access RSE work opportunities, and it was anticipated that RSE employers would look to recruit from all five countries.

Four other Pacific countries have subsequently joined the scheme: Solomon Islands in 2010; Papua New Guinea in 2013; Fiji in 2014; and, most recently, Nauru in 2015, and have also received support from the New Zealand Government.

Despite efforts to create a level playing field a range of factors over the past 13 years have resulted in some Pacific countries having a greater per capita participation in the RSE scheme. The scheme’s demand-driven nature means recruitment is predominantly employer-led rather than controlled by Pacific governments; there is variation in costs and in the ease of recruiting between Pacific countries; and RSE employers prefer to recruit from ‘known’ sources with whom they have established long-term connections.

Combined, these factors have meant employers have tended to favour recruitment from three of the nine participating Pacific countries: Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Pacific RSE arrivals, 2007-2019

In 2018/19, these three dominant Pacific countries accounted for 85 per cent of all Pacific RSE arrivals. The other two early entrant Pacific countries – Kiribati and Tuvalu – continue to struggle to gain traction in the scheme. The more recent participants with much larger populations, like Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Fiji, are experiencing slow growth in numbers while the annual RSE cap remains in place. Relatively small annual increases in the RSE cap mean there are limited opportunities for new entrants to increase their market share.

Demand for RSE employment

In all participating Pacific countries, the available supply of RSE workers is high and outstrips the numbers of RSE jobs available. This is especially the case in countries where the numbers recruited for seasonal work in New Zealand (and Australia) are to date very small.

In Kiribati we interviewed 33 RSE workers, many of whom had been registered with their island councils for at least three or four years before being selected for an RSE job. Some waited as long as ten years for a job offer. Access to seasonal work remains a rare prospect for most I-Kiribati seeking work.

Similarly, in Fiji, the recruitment of new RSE workers is far smaller than the numbers of Fijian citizens seeking seasonal work. Fiji and Kiribati are increasingly looking to Australia for employment opportunities under the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) and the Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) which provides employment opportunities beyond agriculture.

The value placed on RSE jobs, and the time it can take to get one, mean RSE workers and their families want to hold onto them. A common practice among RSE employers is to ask their experienced return workers and team leaders to act as unofficial recruitment agents and to select new recruits for them. This tends to result in the RSE employment opportunity staying within the extended family or village group, rather than spreading opportunities to non-participating households in other areas.

Some RSE employers also reward their experienced workers by allowing for inter-generational transfers of jobs within the family. The RSE employment opportunity is passed from an RSE worker parent to an adult child, ensuring the family retains access to a regular source of RSE income. This practice, while of benefit to the participating household, limits the potential for wider redistribution of work opportunities as people from individual families leave the RSE workforce.

Unequal access to RSE jobs within Pacific countries

Within those Pacific countries able to access RSE employment opportunities, there is unequal access across islands and communities. The preference of RSE employers/recruitment agents to recruit workers from villages with which they are familiar inhibits the spread of economic benefits of RSE employment across the country.

Some villages regularly have large numbers of RSE workers absent each season while others have relatively few or no RSE workers. Participation in the RSE is hotly contested in many places and the absence of any system for sharing opportunities around can exacerbate tensions in communities between those with access and those who are not selected.

Community informants in Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa – three countries which also supply the largest numbers of Pacific SWP workers – reported widening inequalities between participating and non-participating households and communities. In particular, inequalities in access to material goods and funds to pay for services, like education for children, support for the church and family events. Although, there is evidence of some redistribution of RSE income, mainly to support the education of extended family members.

In Vanuatu, evidence of such inequalities can be seen in the built environment where there are clear contrasts between the permanent materials used in houses built by RSE workers, and the more traditional thatched houses that are commonly lived in by those based in rural settings.

New, more equitable approaches to RSE worker recruitment

While the problem of unequal access to RSE jobs among and within Pacific countries plays out at the Pacific end, the cause of the problem is predominantly at the New Zealand end and is linked to the continued existence of the annual RSE cap and the employer-led nature of recruitment.

In an effort to distribute RSE jobs more equitably among participating countries, there are several possible measures from the New Zealand side. These include:

- Large RSE employers (300+ RSE workers) that regularly secure increases in worker numbers of more than a specified minimum each year (say 20 workers) are required to recruit at least half of their new workers from countries other than Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa.

- When allocating new places that arise with increases in the RSE cap, priority is given to workers from countries with low participation rates.

- New RSE employers could be required to recruit their workers from countries other than Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa.

For Vanuatu, Tonga and Samoa – countries that send sizeable numbers of RSE and SWP workers offshore each year – the challenge is to ensure some form of equitable distribution of seasonal work opportunities and income across communities. This requires active management of labour mobility policy settings. In relation to participation in RSE, these Pacific countries could consider the following options:

- Ensuring more equitable distribution of seasonal work opportunities and income across communities to reduce economic disparities and harm to rural communities from excessive loss of productive working-age labour.

- Limiting the number of seasons an RSE worker can return to New Zealand to work and/or introducing a stand-down period after a specified number of years of RSE employment.

- Being directive with RSE employers and labour recruiters about the communities from which they can recruit.

While not underestimating the negative impacts of ongoing COVID-19 travel restrictions on labour supply for New Zealand’s horticulture industry, the current border closures provide an opportunity to re-evaluate some aspects of the employer-led approach to RSE recruitment.

This is a chance for New Zealand and Pacific governments, in collaboration with industry, to decide whether the wide disparities in access to RSE jobs are acceptable and should continue, or whether new, more equitable recruitment approaches should be adopted to ensure the RSE scheme delivers positive outcomes for all participating Pacific countries.

About the author/s

Charlotte Bedford

Charlotte Bedford is a research fellow with the Development Policy Centre and is based in New Zealand.

Heather Nunns

Dr Heather Nunns is the principal of Analytic Matters, a consultancy undertaking public policy research, evaluation and design projects and is based on the Kāpiti Coast, New Zealand.

Richard Bedford

Dr Richard Bedford is Emeritus Professor at the University of Waikato and the Auckland University of Technology.