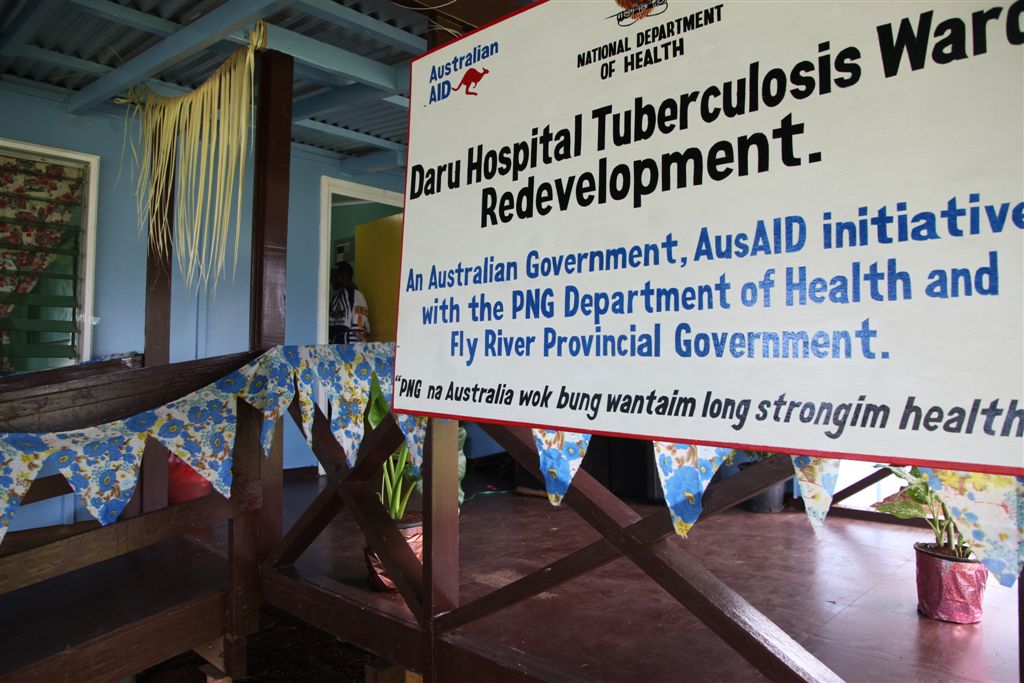

Interim TB ward in Daru, PNG, constructed in 2012 (DFAT/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

Poverty driving TB in Papua New Guinea

By Joyce Sauk

28 September 2018

Tuberculosis is such an old disease, such a normal part of the landscape in many countries, that many governments fail to recognise the extent to which it is a major driver of poverty, with a devastating impact on individuals, families, communities, and the country. In countries with weak health systems, the dangerous symbiotic relationship is even more obvious.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is one of those countries where neglect of the disease through the years has caused the number of cases to spiral exponentially and allowed new drug-resistant strains to develop, resulting in many communities being trapped in a vicious cycle at the interplay of poverty and tuberculosis – one driving the other.

According to the 2017 World Health Organization Global TB Report, TB kills more people in PNG than any other infectious disease. Daru, the capital of the Western Province, has one of the highest rates of multi-drug resistant TB per capita in the world. There were 30,000 new cases of TB in PNG in 2016. As the numbers continued to increase, early this year the Government declared a state of emergency in several provinces, including Gulf Province and National Capital District. The outbreaks are blamed on the Government’s failure to honour its TB funding commitment.

There is no overlooking the conditions of extreme poverty in any conversation about TB in PNG. Living conditions are often over-crowded and insanitary in many settings, both rural and urban. More than two thirds of the population are illiterate and mostly without income, nutrition is poor, and many communities lack access to basic health services. In the remote rural areas, patients can travel for hours or even days to reach a medical facility, costing them up to 100 kina (approximately US $40) for a few hours in a dinghy – one of the most popular forms of transportation in PNG.

Under these conditions, it is no wonder that, for many patients, a TB diagnosis is a death sentence, even though the disease is preventable and curable. In addition to the physical challenges and the difficulty of accessing care, follow-up is also hard. Most drugs must be taken with food, and the treatment period can be as long as two years. Treatment for MDR-TB is even more arduous, and the stigma and discrimination around the disease often serve as a deterrent to those seeking treatment.

The irony is that PNG is resource-rich. Yet it ranks 153 out of 185 countries on the Human Development Index. Alongside its record TB numbers, there are also high rates of HIV and infant and maternal mortality. Weak governance characterised by corruption, high rates of lawlessness, struggling health and education systems, and increased violence against women and children in a male-dominated society are all factors that drive poverty and the conditions that breed diseases like TB.

Widespread illiteracy, for example, means people do not understand what TB is, that it is infectious, and how the infection is passed from one person to the next. Cultural practices, such as the belief in witchcraft or sorcery, also drive behaviours which lead to negative health outcomes.

We need government policies and actions targeted at eliminating the conditions that breed these diseases. Despite receiving millions from the Global Fund and other donor agencies for many years, the government has failed to control or eliminate TB in PNG, because of its failure to address poverty.

The United Nation’s High-Level Meeting on TB alongside the 73rd General Assembly on September 26, will hopefully result in a political declaration on TB endorsed by heads of state. This can then form the basis for TB response in future, including addressing the urgent need to fund programs that look into enablers like life skills and livelihood programs, which are necessary to combat a lifetime of poverty and are the road to eradication of TB in the world.

After years of being at the bottom of the list of global priorities, TB is getting the urgent attention it deserves. For thousands of Papua New Guineans, it cannot come soon enough.

About the author/s

Joyce Sauk

Dr Joyce Sauk is a public health specialist and TB advocate, who survived extra-pulmonary TB 15 years ago. She has worked with the PNG National Department of Health, Port Moresby, for eight years, and is currently pursuing her PhD in Australia.