Last month, the Alliance for Democracies – a Copenhagen-based non-profit – published its Democracy Perceptions Index (DPI). Drawn from over 50,000 survey responses across 53 countries, the Index is one of the largest datasets available on global citizen views of democracy. The Alliance publishes its data set, which allowed us a closer look at the results for South and Southeast Asia.

From an Australian perspective, the DPI is especially timely. A year into its first term, Australia’s Labor government has shown increased interest in the state of democracy in neighbouring regions. A parliamentary inquiry, convened in late 2022, is looking at “how Australia can partner with countries in our region to promote democracy and the international rules-based order”. An Australian Strengthening Democracy Taskforce has been tasked “to bolster Australia’s democratic resilience and enhance trust among citizens, and between citizens and governments”. The collective aim of these efforts is to work out what “supporting democratic trends” could look like across the vastly different countries and contexts in which Australia focuses its development and diplomatic efforts. They reflect renewed vigour in the discussion in Australia about the state of democracy in the region – a discussion that has languished in the last decade or more. They also illustrate a willingness to look at questions of democratic development in a more sophisticated way, eschewing the kinds of knee-jerk judgements that sometimes arise in analyses of democratic trends in the region.

The DPI data is useful from this perspective, as it is based on public perceptions. It provides an interesting complement – and in some senses counterpoint – to assessments that focus on the actions of national governments and the changes they make to the legal and regulatory environment, such as the CIVICUS Monitor, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Report, and Varieties of Democracy Index, or those that assess the quality of elections, such as the Electoral Integrity Project, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, or International IDEA’s Electoral Management Design Database.

For South and Southeast Asia, the DPI data covers eight countries: Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Philippines, Pakistan, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. What does it suggest?

For a start, most people in the South and Southeast Asian countries covered in the survey overwhelmingly say democracy is important, with Pakistan the lowest at 80%. In and of itself, that is an important datapoint to explore when making assumptions about people’s aspirations across Asia.

In addition, most people say their country is democratic. This view is particularly important given the sample countries include several that would not be considered to have democratic political systems by most measures. Interestingly, the survey picked up a high “perceived democratic deficit” (the difference between how important people say democracy is and how democratic they think their country is) in Thailand, where the recent national parliamentary vote resulted in a landslide for the opposition.

These results raise some questions. What is it that people in, for example, Vietnam or Malaysia have in mind when they respond so positively to the question of whether their country is democratic? Is the concept of “democracy” co-opted by populism or nationalism in some countries, such that its meaning is lost? Or do people simply have different values in mind – fairness or equity, perhaps, rather than individual rights? Or something else altogether?

The DPI data drills down on certain components of democracy: free speech, fair elections and equal rights. Aside from Malaysia and Singapore (where just 44% and 40% of respondents, respectively, rated free speech as important), most participants in the other six countries rated all three as important in theory, and identified significant gaps in how they are practised. The gap between perceived importance and reality in Indonesia and the Philippines is particularly striking.

The DPI survey covers several other dimensions of democracy: elite capture, corruption, and threats to democracy, among others. The results for South and Southeast Asia on these issues are also worth exploring. According to the data, between roughly one-quarter and one-half of respondents across seven of the eight countries are concerned about elite capture of politics: they agree with the statement that governments usually act in the interests of a small group of people (Vietnam is an outlier at only 16%). This dissatisfaction is abundantly clear in Thailand, where the figure rises to 55%. While that is a significant minority of respondents in each, it doesn’t discount the fact that the corollary is that most respondents seem to say their governments are acting in a fairly egalitarian manner overall. Perceptions towards elite capture also tend to correlate positively with public perception that a country is undemocratic or has a democratic deficit.

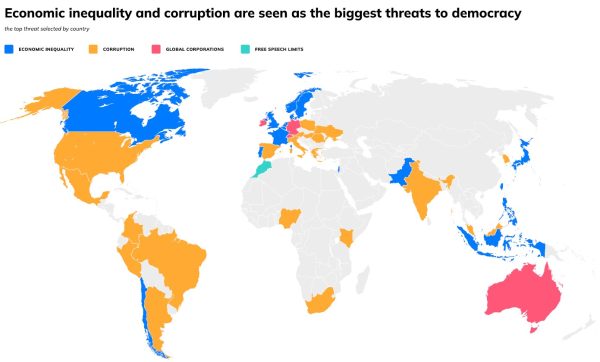

In terms of internal threats to democracy, economic inequality stands out as a significant concern (except in Vietnam), followed by corruption. This echoes recent Pew Center analysis which found that perceptions of the state of the national economy and economic opportunity are the strongest predictor of perceptions towards democracy overall.

Source: Democracy Perceptions Index 2023, page 14.

The survey asks people to rate the importance of various “threats to democracy” such as economic inequality, the influence of Big Tech companies (Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook), limitations on free speech, election interference from foreign powers, unfair elections and/or election fraud, corruption, and the influence of global corporations. Australia stands out with a majority view that global corporations pose the biggest threat to democracy, in contrast to not only Asia but most countries surveyed.

Regarding external threats, most people surveyed see war and violent conflict, poverty and hunger, and economic instability as the three greatest global challenges.

Source: Democracy Perceptions Index 2023, page 54.

What does all this suggest from a development policy perspective?

The survey results – in what they don’t capture as much as what they do – underscore the complexity of views, beliefs and values around democracy in the region. One way in which Australia might “listen to the region” would be through better understanding of local conceptions and prioritisation of democratic principles (such as rule of law, separation of powers, free and fair elections) and democratic ideals/values (for example equality, justice, participation, pluralism, accountability and transparency).

The survey data also indicates priority areas for building democratic resilience, for example, strengthening governance that delivers for most instead of a small minority and that does so in ways that tackle corruption. It reminds us that a focus on economic development in donor aid strategies is critical, but that focus should go beyond macro-economic considerations to individual and community wellbeing and equality, and seek to understand the intersection of economic, political and social development trajectories. And finally, that responding to economic inequality – or perhaps inequality more broadly – should be considered a significant pillar in Australia’s engagement with the region.

Source: Democracy Perceptions Index 2023, page 25.

Disclosure

This post is part of a collaborative series with The Asia Foundation.

Leave a Comment