Should aid practitioners worry about economic inequality?

By Terence Wood

6 July 2015

Is economic inequality important for aid work? This was the question I asked myself when I saw the name of this year’s ACFID University Network Conference: “Evidence and Practice in an Age of Inequality”. (The title didn’t specifically mention economic inequality, but conference material suggested it was the topic at hand.) It was an interesting theme; yet as I mulled it over I couldn’t convince myself that economic inequality ought to be high on the list of issues aid workers anguish about.

That’s not to say I think economic inequality is a good thing. As a utilitarian who believes the evidence showing that when you are poor more money improves your well-being considerably, but that when you are wealthy more money makes little difference, I think unnecessary inequality is bad.

But this doesn’t mean economic inequality is necessarily something aid practitioners should be worrying about a lot in their day jobs. For this to be true we need evidence that actively tackling inequality in developing countries is of central importance in increasing the wealth (and therefore well-being) of poor people. We also need evidence aid is likely to be a powerful instrument in tackling economic inequality. And, because our money, time and ideas are finite, we need cause to believe reducing economic inequality is more important than all the other things we could be working on, or worrying about.

There is good evidence poorer countries are, on average, home to lower levels of well-being. And we live in a very unequal world which, if it were to become more equal by virtue of its poorest people becoming wealthier, would be a better place. But the core problem here isn’t that the world’s poorer countries are particularly unequal; the problem is that poor countries are poor. Which means that if we want to reduce economic inequality globally and, through this, increase well-being, economic development is needed.

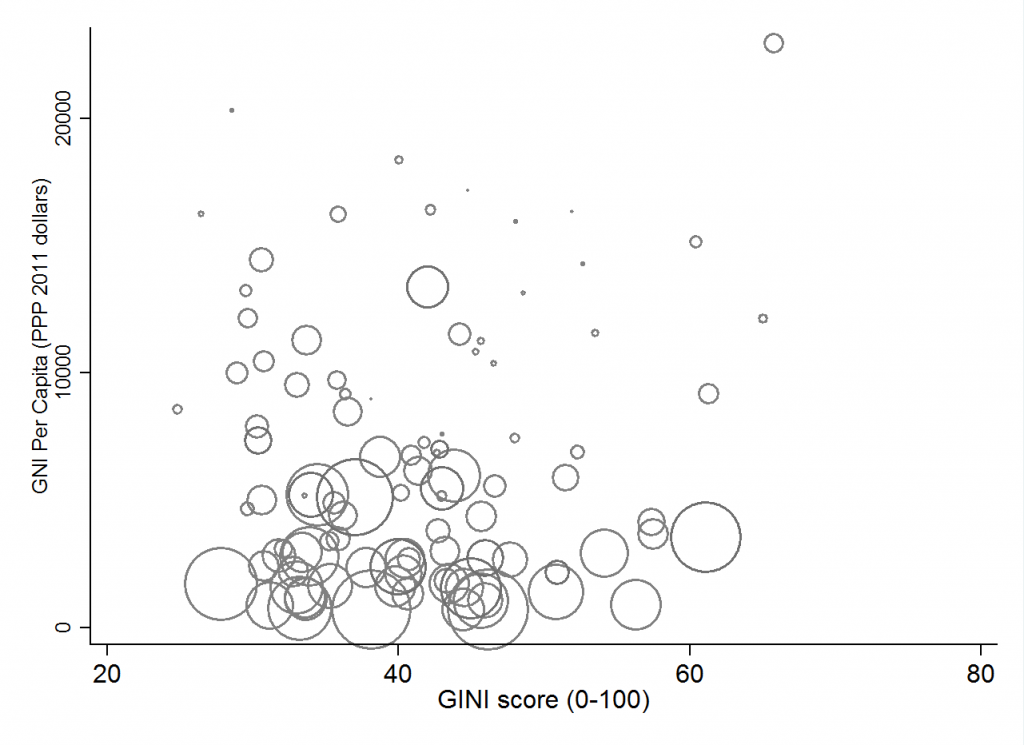

Of course, it’s best if, as economies grow, they reduce inequality too, but for poor countries, overall wealth is more important than issues of distribution. True, some aid-recipient countries are both comparatively wealthy and also very unequal (for example, Brazil), and in these countries reducing economic inequality has considerable scope for reducing poverty. However, this is where the question of aid’s potential influence is important. In countries where reducing inequality can significantly help in reducing poverty, is it reasonable to expect aid to have much influence on inequality? In the chart below I’ve plotted national wealth (GNI per capita) on the Y-axis versus inequality on the X-axis (measured by the GINI coefficient). Each circle is an aid recipient country. Countries in the top right of the chart (unequal and comparatively wealthy) are countries that have the most potential to tackle poverty through reducing inequality. To capture the potential influence of aid I have scaled the size of each country circle to reflect aid as a percentage of GNI. (Data sources and notes can be found on page 8 of this PDF.)

Figure 1: GNI per capita versus GINI score for aid recipient countries

Some unequal and comparatively wealthy countries receive aid. But the bulk of countries where aid might reasonably be assumed to have potential economic influence (the larger circles) are down the bottom of the chart: countries where growth is a more important condition for reducing poverty and improving well-being.

Some unequal and comparatively wealthy countries receive aid. But the bulk of countries where aid might reasonably be assumed to have potential economic influence (the larger circles) are down the bottom of the chart: countries where growth is a more important condition for reducing poverty and improving well-being.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean aid should focus on fostering economic growth alone. While there’s a relationship between wealth and well-being, other things matter, and it isn’t clear that aid is particularly effective in boosting economic growth in some contexts (this is something I cover in this paper, and these blog posts). Aid should focus on economic development when it can do so productively, but focus on other areas (health, empowering women, promoting political participation, etc.) in contexts where it can deliver more in these areas.

Ultimately, something similar strikes me as true with economic inequality, and whether we should worry about it in aid work. Economic inequality is an issue, but it is not the only economic issue that matters. It’s also the case that economic inequality isn’t the only form of inequality confronting aid work. And other types of inequality are often more central to aid practice.

Think about gender inequality: domestic violence rates are abysmal in Pacific countries such as Solomon Islands while women’s political representation is very low across the Pacific (see page 3 of this PDF). Or to give another example of particular relevance to the work of the Australian aid community, in one fell swoop Joe Hockey was able to cut Australian aid by 20 per cent. Here we have a form of acute political inequality: one man can make a decision that will potentially affect the lives of hundreds of thousands of people who can’t vote in Australia, and justify it with spurious arguments; and the Australian aid community has yet to find an effective way of countering this. This isn’t for want of trying, people are campaigning against the cuts, but it’s not easy. Likewise, enduring gender inequalities in the Pacific continue in spite of our efforts to counter them.

Of course, sometimes economic inequality is tangled up with these other types of inequality (one of the problems women face in elections in Solomon Islands is that they don’t have the money male candidates do) but this isn’t always the case (money doesn’t explain domestic violence, and it’s not clear that we’re losing the fight on aid funding because we have too little money to campaign with).

And this is the source of my concerns about aid workers, and academics with an interest in aid, getting too caught up on the issue of economic inequality. It’s not that it doesn’t matter: it does, but the inequalities that matter most for actual aid practice, and the inequalities that we still don’t know enough about tackling aren’t, first and foremost, ones to do with money.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His PhD focused on Solomon Islands electoral politics. Previously he worked for the New Zealand Government Aid Programme. This blog is based on a presentation given at the 2015 ACFID University Network Conference. You can download the presentation, with speaking notes and charts, and data sources, here.

About the author/s

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.