Sometimes corruption makes sense: insights from research into Papua New Guinean understandings of corruption

By Grant Walton

4 December 2013

As discussed in this blog, I recently helped launch a report on Papua New Guinean perceptions of corruption. The report focused on findings from a household study undertaken in 2010/11. Preceding this study, in 2008, I was engaged by Transparency International PNG – who were funded by the agency formally known as AusAID – to conduct focus groups in rural locations in Madang, Southern Highlands, East New Britain and Milne Bay provinces. The aim of the research was to better understand citizens’ understandings of corruption. We conducted 64 focus groups with 495 people in two locations in each province: one remote and one close to resources. The results of these focus groups informed the larger household study.

This blog summarises the findings from focus groups, and reflects on what they mean for addressing corruption in PNG.

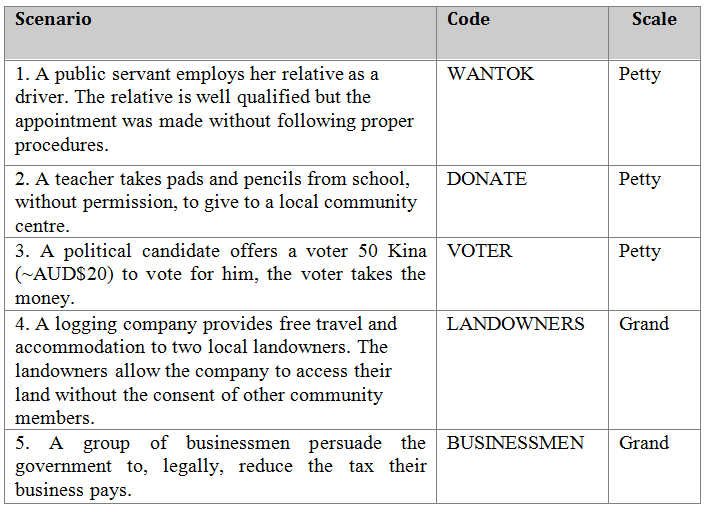

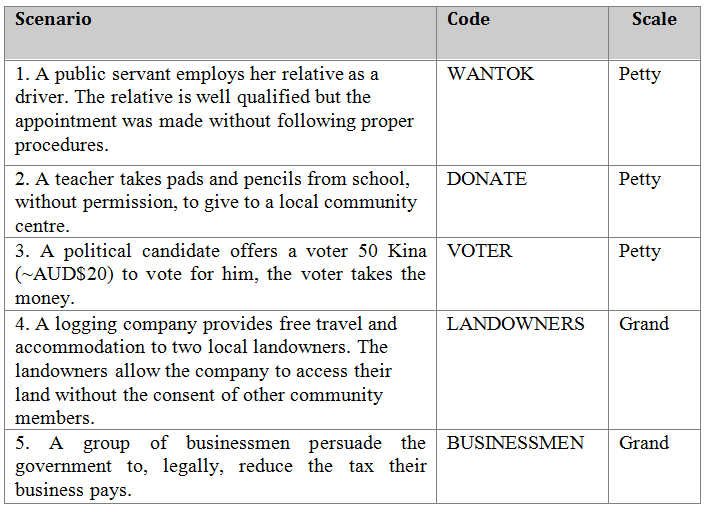

Focus group participants were asked a range of questions; this included responding to five scenarios that represent different scales and types of possible corruption. As shown in Table 1, three scenarios represented possible petty corruption while two represented possible grand corruption. Scenarios involved public officials, the private sector and citizenry, and featured embezzlement, abuse of power, bribery and nepotism. Respondents were presented with these scenarios and asked: 1) if the type of activity mentioned occurs in PNG and why it does or does not; 2) what they thought about the actors mentioned in the scenarios; and 3) what they believed the consequences of such scenarios would be.

Table 1: Scenarios

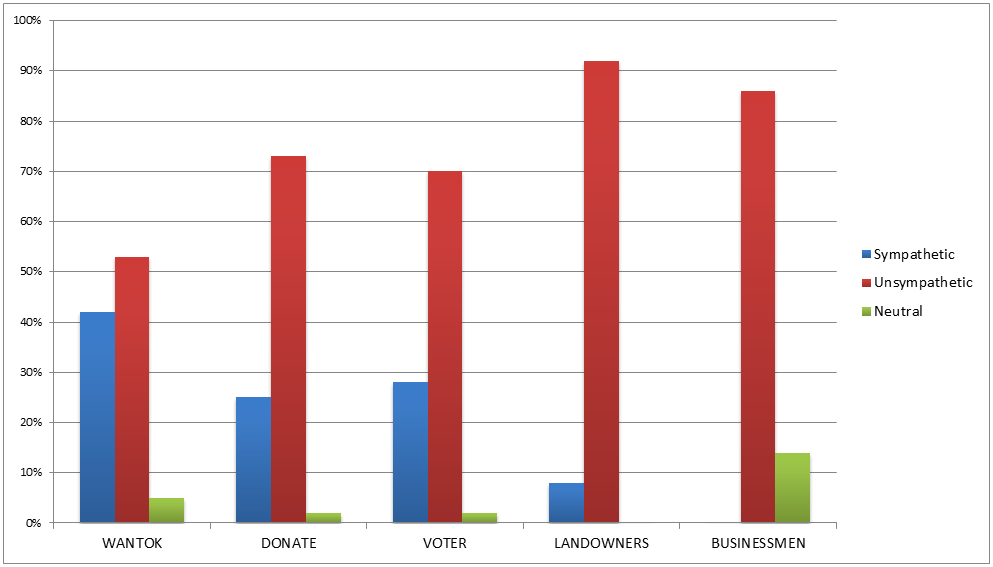

When analysing the results, focus groups were categorised by whether or not respondents were sympathetic to one or more of the respondents depicted in the scenarios. As Figure 1 illustrates, most were not sympathetic. However, there were significant differences between responses to scenarios suggesting different scales of corruption; more focus groups were sympathetic to those engaged in petty corruption.

When analysing the results, focus groups were categorised by whether or not respondents were sympathetic to one or more of the respondents depicted in the scenarios. As Figure 1 illustrates, most were not sympathetic. However, there were significant differences between responses to scenarios suggesting different scales of corruption; more focus groups were sympathetic to those engaged in petty corruption.

Figure 1: Responses to scenarios

Unsympathetic respondents rallied against what they saw as the transgression of rules and laws. This was particularly the case with the Wantok scenario, with respondents – particularly those with higher levels of education – concerned that the public servant knowingly abused the official appointment process. As a result, one male from Milne Bay said, ‘if I missed out on this [job] I would be angry… it’s not right’. Respondents were also concerned about the impacts such transactions could have on their communities. In response to the Donate scenario, a young male in his twenties from Madang, said such acts, ‘deprive children of learning’. A female in Milne Bay feared that ‘the school will run out of materials and [children] will give up school’.

Unsympathetic respondents rallied against what they saw as the transgression of rules and laws. This was particularly the case with the Wantok scenario, with respondents – particularly those with higher levels of education – concerned that the public servant knowingly abused the official appointment process. As a result, one male from Milne Bay said, ‘if I missed out on this [job] I would be angry… it’s not right’. Respondents were also concerned about the impacts such transactions could have on their communities. In response to the Donate scenario, a young male in his twenties from Madang, said such acts, ‘deprive children of learning’. A female in Milne Bay feared that ‘the school will run out of materials and [children] will give up school’.

Responses to both scenarios depicting grand corruption were overwhelmingly unsympathetic. Most responding to the Landowner scenario were concerned about negative social and environmental consequences. For example, a male in Madang, said, ‘this is happening now to us, the company has destroyed our natural resources, we have nothing’. Responding to the Businessman scenario, respondents feared a reduction of social services, and that the company would increase the price of their goods regardless. In other words they believed they would see no benefit from the business having a lower tax rate.

Unsympathetic respondents were, at times, passionate about disciplining those involved in the scenarios. They spoke of taking wrongdoers to court (although many doubted the effectiveness of this strategy) and even beating them up.

Sympathetic respondents highlighted the social, cultural and economic factors that shape such transactions. Many suggested that scenarios reflecting possible petty corruption could help address poverty. One male from East New Britain said that the public official’s relative employed in the Wantok scenario was likely poor and that getting a job, no matter what the circumstances, meant they ‘could now eat rice’.

Some believed the scenarios could redistribute state resources. Responding to the Voter scenario, a male from Southern Highlands, summed up this position, saying, ‘such bribes should be given to the whole community and leaders so every one benefits and not only a few people’. Respondents also spoke about the importance of kinship ties. Responding to the Wantok scenario, a man from the Southern Highlands said the public official was right to employ her relative as she was acting out of ‘traditional obligations’, and rightly supporting a member of her tribe.

Females, those who identified as illiterate, and those from the most remote villages were most likely to sympathise with scenarios depicting petty corruption. It was these groups who were least likely to understand state rules and laws, and expressed concern that they were excluded from state resources.

Conclusions emanating from this research are discussed in length elsewhere (see pay-walled article here; and online report here), for the purpose of this blog I’ll conclude with two points. First, understanding corruption in PNG means acknowledging the context in which these transactions occur. There is a tendency in the corruption literature and the policy documents of donors to view all forms of ‘corruption’ in a normative light: corruption is considered immoral behaviour that can only lead to dysfunctional outcomes. While most respondents supported this view, sympathetic respondents highlighted how social, economic and cultural factors play an important role in attitudes towards (particularly small-scale) corruption in PNG.

This suggests that ignoring how marginalised communities can benefit from corrupt transactions, in the midst of a weak state, can misrepresent the problem and overlook the reasons for citizens supporting those who engage in corruption.

Second, findings suggest that mitigating corruption in PNG will require a broad range of approaches. With some respondents unsure about the laws and rules that applied to the scenarios, it is important to educate citizens about the law, as well as their rights and responsibilities (proper voting practices, for example). Many unsympathetic respondents were keenly concerned about the activities depicted in the scenarios and suggested that they would take action against those involved. This suggests it is important to improve mechanisms for reporting corruption and to support those who are willing to report it.

However, responses also suggest that there are constraints on collective action against corruption. In rural settings where there are strong cultural ties and a weak state, supporting corruption can make sense. Given this, encouraging collective action against corruption in PNG remains a key challenge for policy makers.

There’s no quick fix to this challenge; but here’s a couple of ideas that might help. First, encouraging collective action could mean working with communities to demonstrate how, by following due process, the entire community – particularly the poor and marginalised – can tangibly benefit from developmental processes. This could include mobilising communities to keep the development actors accountable when providing health, education and infrastructure (as explored in this blog).

It may also require encouraging cultural practices that deter corruption and support openness and transparency. This approach has been taken by the PNG Department of Personnel Management, which has drawn on local and Western ethical frameworks to develop their new Leadership Capabilities Framework (highlighted in this blog). The effectiveness of this program is still not clear, but such approaches are important for discovering how culture might augment anti-corruption efforts.

Some fear that highlighting structural constraints (such as the impacts of culture and poverty) in debates about corruption, can excuse corrupt behaviour. However, not acknowledging these factors runs the risk of misunderstanding the problem of corruption, and failing to meaningfully address it.

This blog is based on a recently published article (pay-walled) in the journal Public Administration and Development and a preliminary findings report [pdf] published by Transparency International.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

About the author/s

Grant Walton

Grant Walton is an associate professor at the Development Policy Centre and the author of Anti-Corruption and its Discontents: Local, National and International Perspectives on Corruption in Papua New Guinea.