The 2019 Australian aid transparency audit

By Luke Minihan and Terence Wood

19 February 2020

All government spending should be transparent, but aid transparency is particularly important. Aid is spent overseas, which makes it much harder for the public, journalists and independent experts to monitor. Unless the government makes comprehensive information about the aid it spends easily available, it’s almost impossible to work out if that money – which comes from the taxes we all pay – is being spent well. In late 2019 the Development Policy Centre audited the transparency of the Australian Government Aid Program. This was the third time we’d conducted such an audit; we’d run audits previously in 2016 and 2013.

The 2019 Devpolicy transparency audit (the full report is online here; underlying data here) focused on three aspects of transparency, all to do with information on specific aid projects, and based on what we could find on the Aid Program’s website – which these days is its main window to the world. First, we estimated what share of substantial aid projects are listed in any way on the website. Second, we worked out what share of those projects on the website contained at least some very basic information on the project (budget, start dates, end dates, and the like). And, third, we worked out what share of the projects listed on the website had detailed information like planning documents, performance management documents, and reviews and evaluations available online. We focused on these types of document, because they’re the documents you need if you’re to have any chance of learning what a project is really about, and whether it is being run well.

The Aid Program is transparent in other ways that weren’t captured in our audit. For example, it provides an excellent time series of the amount of aid it has given to countries over the years. And it reports on its projects to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) and to the OECD. But the time series on the website, while invaluable, only deals with high-level information – it doesn’t focus on individual aid projects. And IATI data are all in XML, which is great for computer programmers, but is about as useful to the average person as etchings on clay pottery buried under an ancient Italian volcano. A patient person can make use of the OECD data, but it’s only released several years after the fact, and are scant on details. We believe full transparency requires a rich set of information on all significant aid projects, presented in a timely manner, in a way that the average person can make use of. That’s what we audited.

Because out audit was manual, to make it manageable, we focused on a subset of the countries Australia gives aid to, but we made sure it included the largest recipients. In particular, we looked at the Pacific countries, Indonesia, and a random set of countries elsewhere (the countries are listed in the audit report). This approach gives a broadly representative picture of the Australian Government Aid Program’s work. We focused on the same recipient countries in 2019 as in 2016, and these countries were very similar to those used in 2013. We used very similar methods in all years. This means we can compare transparency across time.

There’s much more in the report, but here are three key findings.

To estimate what share of significant Australian aid projects are mentioned on the website at all, we compared 2016 Aid Program website data with 2016 OECD CRS data. (By ‘significant’ we mean projects that are not very small.) We had to focus on 2016 because that’s the most recent year website data and CRS data exists. When we did this, we found that about 85 per cent of significant projects in the typical recipient country we studied made it online. This is a pretty good starting point, although Australia’s reporting was worse for some important recipients, notably Solomon Islands.

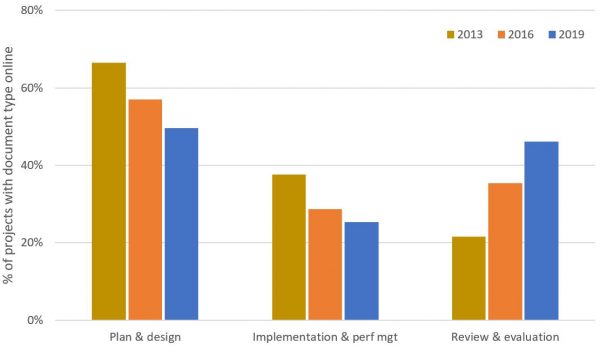

When we looked at the availability of basic information for those projects that were listed in some form on the website, we found that, on average, availability of basic information fell from 2013 to 2016. You can see this in the chart below.

Figure 1: Availability of basic project information

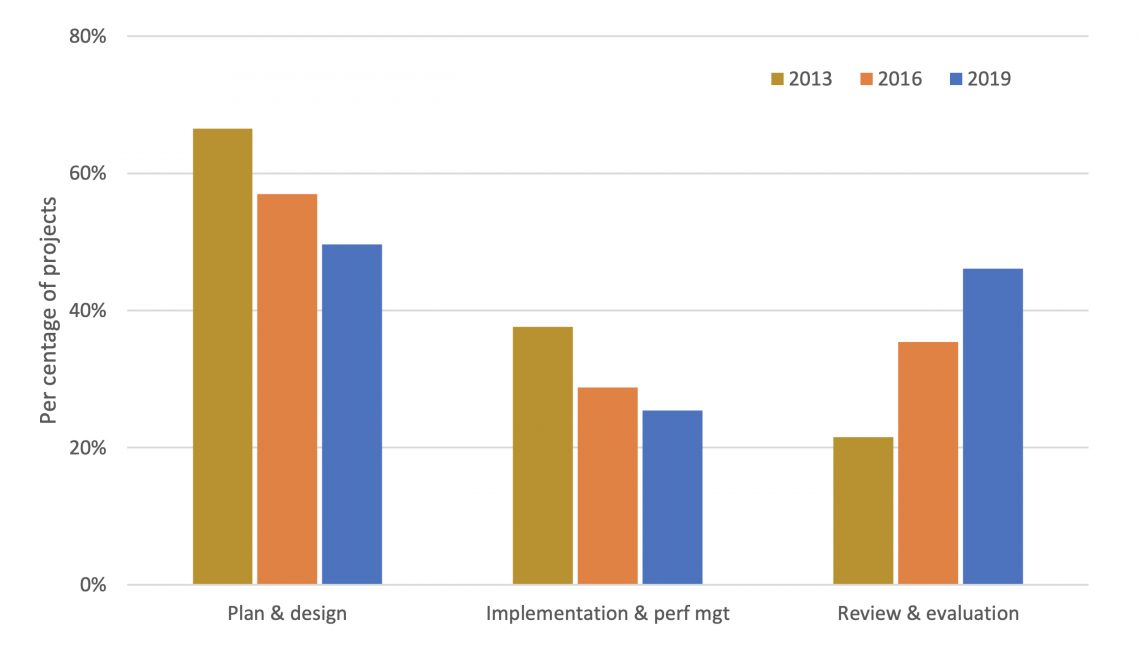

When we looked at the availability of detailed information on projects, we found an interesting divergence in trends. As Figure 2 shows, transparency fell for planning and implementation documents, but improved for reviews and evaluations.

Figure 2: Availability of detailed documents by document type

From our qualitative knowledge of the Aid Program, we think one of the main reasons reviews and evaluations bucked the trend of declining transparency was the ongoing work of the Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE), the entity tasked with improving the practice of evaluations in the aid program.

We also conducted quantitative analysis to see what types of projects were most likely to have a full set of detailed documentation online. When we did this, we found no obvious evidence that matters of political economy were impeding transparency. Transparency seemed no worse for projects in countries that might be assumed to be politically sensitive. Instead, our clearest findings were that transparency was worse for smaller projects. We also found projects that started their lives transparently tended to stay more transparent (this is even after taking size into account).

We think there are important lessons in what we found. The success of the ODE’s work on the publication of evaluations shows one means of the Aid Program fostering transparency would be to create its own specialist transparency unit, tasked with educating staff about what they should be putting online, and reminding them of the need to put key project documents online.

Poor transparency among smaller projects suggests time may be a constraint. Because of this, streamlining systems may help with transparency by making it easy for busy staff to place appropriate documents online.

Finally, the finding that aid projects that start transparently are more likely to stay transparent, provides evidence of potential easy wins associated with ensuring that good practice is followed (and understood) right from the beginning of individual aid projects.

In 2013, Julie Bishop stated, ‘as transparent as AusAID has been, we can be more transparent’. The sentiment aspiration was right, but as our aid transparency audits have shown, aid transparency has fallen in the years since Bishop said this. Political commitment from future governments could help turn declining transparency around, but in the meantime there are also basic procedural changes that the Aid Program could make if it wants to be appropriately open with Australians about how it spends their money.

Terence Wood will present the findings of the 2019 Australian aid transparency audit at a keynote panel, Australian aid: PNG and transparency, on Wednesday, 19 February at the 2020 Australasian AID Conference. The conference program and single session tickets available here.

About the author/s

Luke Minihan

Luke Minihan is a Research Assistant at the Development Policy Centre. He is an undergraduate student at the Australian National University studying a Bachelor of Politics, Philosophy and Economics and Bachelor of Arts majoring in Development Studies.

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.