The legacy of technical assistance in Afghanistan

By Mary Venner

24 January 2023

A few months after the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, I wondered what would become of 20 years of public sector reform and technical assistance now that international donors and foreign advisers had left.

There were many reasons for assuming that the hard work and resources invested by the international community would now be wasted. The previous Taliban government, before 2001, was known for public sector dysfunction and neglect. Now the returned Taliban trumpet their success in freeing the country from what they see as foreign control and are strongly resistant to any international influence. In many policy areas they define their regime in opposition to all things Western.

Certainly, the Taliban authorities have rapidly jettisoned many of the ideas and institutions created over the past 20 years, retaining only those that help consolidate their power. Since taking control they have dismissed the parliament and returned to rule by decree, dismantled institutions such as the Human Rights Commission and independent oversight of the public service, introduced surveillance of the media and issued rules about what they can report, violently suppressed public demonstrations, imposed extreme restrictions on the rights and freedoms of women, and subjected the population to unpredictable and arbitrary exercise of power.

There is no way the current Taliban-controlled administration would meet most donors’ criteria for good government. On this basis, the US Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) has judged the entire institution building effort in Afghanistan a failure.

But not every idea brought by the West has been rejected. In some areas of day-to-day public administration it appears the new regime has simply continued the existing activities of the previous government, more or less unchanged, including applying many of the ideas and processes introduced by foreign advisers under donor-funded capacity development programs.

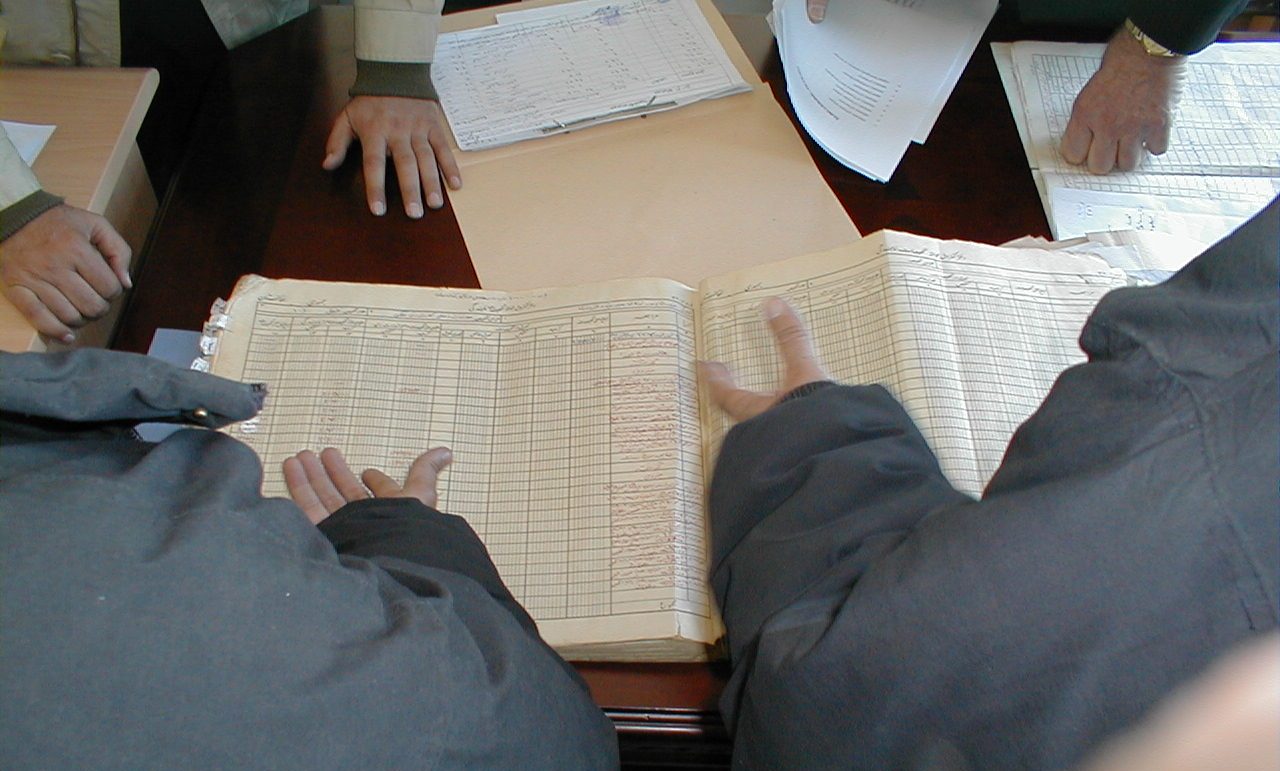

In the field of public finance, for example, the technology and systems introduced by donors to improve and modernise Afghanistan’s budget processes, tax administration and monetary policy are still being used by the new rulers, and they seem to recognise the value of the professional skills they have inherited. Although Taliban-aligned clerics, many with no relevant experience, now control all government bodies, and donor-funded experts have been withdrawn, many of the men (but no women) who previously worked with and were trained by international experts remain in place and are continuing to implement, at least for the time being, the systems established with the help of external advisers.

The Taliban Ministry of Finance is a prolific user of the internet, Twitter and YouTube. It rapidly took control of the websites and social media accounts of the previous government and now uses them in much the same way to provide information on its activities. With the help of rough Google translations, these provide insights into how the new regime is operating. The Ministry produces a constant flow of news reports and Twitter posts, in Pashto, Dari and sometimes English, about high level meetings, the recruitment and training of new staff, and requests for tenders. The Audit Follow-Up Committee has reported on its activities, and a tax law and procedures seminar was held at Kabul University.

The Ministry’s posts have also included information about Taxpayer Identification Numbers (TIN) and the SIGTAS tax management system, a video promoting the benefits of the ASYCUDA customs data system, and another explaining the operations of the Afghanistan Financial Management Information System (AFMIS), all of which were the products of foreign technical assistance. The Ministry recently announced the commencement of the 2023-24 budget preparation process with a two day seminar for government departments, following the procedure adopted by the previous government.

There may, of course, be a difference between public announcements with slick promotional videos and how well these systems and processes are actually being used. Occasionally, public responses to official Twitter posts question the reality of the situation on the ground, including comments about access to ASYCUDA or SIGTAS, concerns about the fairness of recruitment campaigns, and delays in the payment of salaries and pensions.

The Taliban have good reasons for taking a close interest in public finance processes. Prior to the Taliban takeover, 75% of government funds were provided by donors (in itself perhaps a sign of a failure of institution building). Now that this source of finance has been abruptly terminated, the Taliban depend on domestic revenue to keep the public sector operating. They are, therefore, particularly focused on tax collection.

The Revenue Department issues frequent media announcements, including updates on the amount of revenue collected in each province, and reports on the seizure of smuggled goods at border posts and the arrest of customs employees charged with accepting bribes. A recent report by the Afghan Analysts Network suggests that Taliban tax collection is organised and systematic and appears to be far less corrupt than under the Republic.

What happens to collected revenue after it goes into the Taliban government’s accounts is another matter. Transparency in public finance is not a Taliban strong point, despite their claims to the contrary. Little information is available on the Ministry of Finance website about the annual budget, apart from an announcement about aggregate revenue and spending estimates. The previous government’s regular online posting of economic and financial reports has largely been abandoned.

The Taliban are also keen to convince international bodies to return government assets frozen in foreign bank accounts. The regime has tried to assure the US and other foreign governments that it has the staff and the systems to meet international monetary policy standards, including the prevention of money laundering and financing of terrorism. Like the Ministry of Finance, the Afghan Central Bank produces a torrent of Twitter posts about its activities, including efforts to recruit senior bank supervision and anti-money laundering staff.

What are we to make of the Taliban’s adoption of these public finance systems introduced under the auspices of capacity development projects? Should we be pleased that the processes for effective revenue collection and budget management – as well as, it seems, procurement procedures, recruitment processes and audit reporting – that were introduced through donor initiatives are still being used, and that many of the Afghans who were trained to implement them continue to perform their roles effectively?

Or should we be dismayed that the systems designed to improve government effectiveness are potentially propping up a regime we find abhorrent and are used to harm rather than help?

These are difficult questions, well beyond the scope of this blog. But it is certainly interesting that, in a world in which many complain that donor-funded reforms do not “stick”, some seem to endure even in these difficult circumstances. The situation in Afghanistan may, in the long term, provide evidence about which reforms and what kinds of donor interventions are more likely to survive even when international observers leave.

About the author/s

Mary Venner

Mary Venner worked as a technical adviser with the Afghan government between 2003 and 2007 and is a professional associate at the University of Canberra. She has written on post-conflict reconstruction and public administration as well as on her personal experiences in developing countries.