In April 2018, China established its stand-alone aid agency – the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA). This was a milestone event in Chinese aid history and signalled China’s ambition to reform its aid management to achieve better coordination and greater impact of its aid programs. On CIDCA’s two-year anniversary, we take a look at what has changed and what remains the same, and implications for external stakeholders who engage with China on development cooperation.

What has changed?

With the creation of CIDCA and its place within the Chinese government system, the role of foreign policy (and by extension that of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, MFA) in China’s aid policy has been boosted. While foreign aid was primarily managed by the Department of Foreign Aid within the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) before, CIDCA (a vice-ministerial agency) is directly under the State Council and placed under the supervision of State Councillor Wang Yi, Minister of MFA. This arrangement increases the voice of foreign policy/MFA in Chinese aid decision making, as China’s diplomacy under President Xi Jinping has been moving away from ‘hiding the strength and biding one’s time (taoguang yanghui)’ and becoming more proactive. The Chinese government is increasingly using aid to serve diplomatic and political purposes. For example, China pledged considerable amounts of aid to Solomon Islands and Kiribati, two Pacific island countries that switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in September 2019.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been at the core of Chinese aid program under CIDCA since its inception – unsurprising as the government made it clear at the time of CIDCA’s creation that the use foreign aid to support the BRI would be a main goal of CIDCA. BRI is anchoring China’s bilateral relations with recipient countries, and foreign aid is playing a significant supporting role in this process. Partner countries have expressed strong support for the BRI, and grant and financing commitments have featured prominently in CIDCA’s bilateral meetings.

What remains the same?

Despite CIDCA’s creation, much has remained unchanged in the management of the aid system. On an ideological level, China continues to define its aid within the South-South Cooperation framework, distinguishing Chinese aid from traditional aid in the sense that China, as a developing country itself, is only doing what it can within its capacity to help other developing countries. This self-positioning highlights the importance of siding with the developing world as a cornerstone of China’s diplomacy.

With CIDCA’s mandate in the aid program chain concentrated on planning and designing at the front end, and monitoring and evaluation at the back end, the aid implementation remains unchanged. This gives the other agencies ‘skin in the game’. Technical and line ministries are still the direct implementing agencies for programs in their technical areas. The three implementation arms of Chinese aid continue to play their respective roles. That is: the Executive Bureau of International Economic Cooperation manages both ‘complete projects’ (or turnkey projects) and technical cooperation activities; the China International Centre for Economic and Technical Exchanges oversees in-kind donations; and the Academy for International Business Officials is responsible for provision of training to officials from partner countries. All three arms remain under MOFCOM’s jurisdiction.

In this structure, MOFCOM continues to wield substantial influence on Chinese foreign aid, even if it is no longer the main caretaker. Therefore, economic interests will remain relevant alongside China’s diplomatic and other considerations in deciding aid allocation. The Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation (CAITEC), a think tank that, among other responsibilities, provided counsel on aid and development cooperation to MOFCOM’s Foreign Aid Department in the past, is now providing similar counsel to CIDCA on aid issues but remains affiliated to MOFCOM. The composition of CIDCA staff also explains the relevance of MOFCOM to Chinese aid. Staff from MOFCOM’s Department of Foreign Aid became the backbone of staff at CIDCA and account for the majority of aid technocrats there. Of the total 19 directors and deputy-directors that lead CIDCA’s seven departments, 11 are former MOFCOM officials. Eight of the 11 lead CIDCA’s core departments on aid planning, supervision, and regional affairs (in charge of bilateral aid).

At the time of its creation, CIDCA rekindled hope among Chinese NGOs that there would finally be a designated agency for China’s foreign aid and that the agency might lead the way in defining the role of (and allocating aid budget to) Chinese NGOs in the delivery of Chinese aid. Chinese aid projects have long been criticised for lacking a community touch and China’s efforts to promote the BRI have heightened such criticism and grassroots suspicion of Chinese intentions. What better way to improve China’s image and strengthen people-to-people links with partner country communities than to allow Chinese NGOs to get some funding from China’s aid budget and play a more active role in delivering community-focused projects? Those who have had this hope are disappointed. CIDCA has so far paid minimal attention to working with or setting up partnerships with Chinese NGOs. This issue is apparently a low priority on CIDCA’s busy agenda.

Implications for external stakeholders

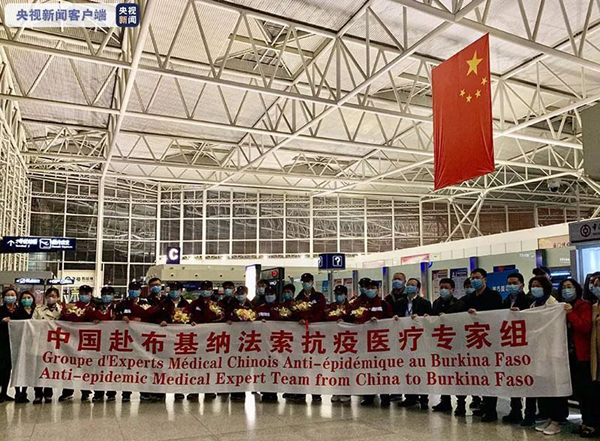

For OECD DAC donors looking to engage with China on aid coordination and trilateral cooperation, the continuing fragmentation of China’s aid structure means that they also need to adjust their expectations. CIDCA is of course the natural counterpart to talk to, especially if one is looking to see Chinese funding contribution to a trilateral program arrangement. With line ministries outside of CIDCA continuing with their respective aid programs (in the form of medical teams under the management of the National Health Commission, or agricultural expertise and machinery under Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs for example), CIDCA has become just another department DAC donor country staff in Beijing need to reach out to, to talk about possibilities for trilateral cooperation.

As for engagement with partner countries, not much has changed. CIDCA’s total staff number is just a few dozen and consequently it does not have staff deployed on the ground. The Economic and Commercial Counsellor’s Office (with staff posted from MOFCOM) in Chinese embassies continues to be the point of contact for partner countries. With the recent global outbreak of COVID-19, there has been tremendous demand from partner countries for Chinese medical supplies and technical expertise. CIDCA has been coordinating with MFA (including Chinese embassies overseas), MOFCOM, the National Health Commission, and a number of other related ministries on the COVID-19 response, which is described by CIDCA as “the most intensive and wide-ranging emergency humanitarian operation since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949”. Such an enormous exercise has put to the test CIDCA’s coordination with the various agencies since its creation and the jury is still out.

Two years is a short time to have a fully functional new agency – even just updating past aid regulations and updating the branding has taken a lot of time. Hopefully, CIDCA’s role and responsibilities will be further clarified in the months and years to come, and it will live up to the expectations of strengthening aid coordination in China and providing greater opportunities for development cooperation with other donor countries.

Leave a Comment