(Credit: MarksPhotoTravels-Donation box/Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The ongoing slide in donations to Australian NGOs

By Terence Wood

25 November 2019

Money isn’t everything. But if you’re an aid NGO, revenue makes it a lot easier to help people. We now have data on NGO revenue in 2018, which we’ve added to the Devpolicy time series.

Based on my analysis of members of the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID), as well as MSF and Compassion (two of the largest non-ACFID members), it looks as if total revenue for Australian aid NGOs crept up between 2017 and 2018. The increase was so small, however, that once inflation is taken into account, it actually became a slight decline. (You can see data and a chart of total revenue in a file here. This file also explains our methods and assumptions.)

What’s more, as you can see in the chart below, while revenue from all sources crept up nominally, public donations to NGOs fell for the third year in a row.

Public donations to Australian aid NGOs

One possible explanation for falling donations – an explanation that would count as good news – would be fewer humanitarian emergencies, and fewer donations as a result. It’s hard to work out how best to measure those humanitarian emergencies that would be likely to have an impact on donations to Australian NGOs. One approach is to look at how much Australian NGOs are spending on humanitarian projects (as opposed to broader development projects) every year. The assumption in this approach is that spending ought to roughly reflect need. When I did this, I found that humanitarian spending actually rose slightly between 2017 and 2018, suggesting an increase in need. What’s more a look at Pacific data from the EM-DAT, the Emergency Events Database, shows 2018 to have been worse for disasters in our region than 2017, and yet donations fell. A fall in disaster-related need does not seem to be the main explanation for falling donations in 2018.

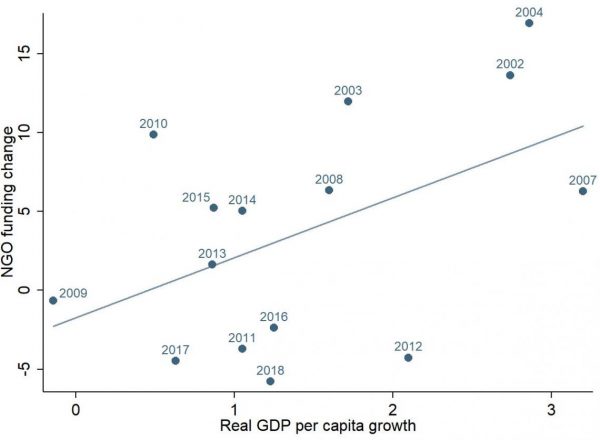

Another possible explanation for falling donations is the state of the economy in Australia. People, presumably, will be less likely to donate when their personal financial circumstances are less secure. I wrote about this in 2017, explaining that there appeared to be an empirical relationship between donations and the state of the economy (as proxied by economic growth). The relationship I identified then is still present (and statistically significant, at p<0.05). The scatter plot below illustrates it.

Relationship between economic performance and NGO donations

As the scatterplot shows, while the relationship is real, the correlation between growth and the rise and fall in donations isn’t perfect. Factors other than the broader economic environment in Australia contribute to people’s propensity to give. Often, rises and falls in donations are greater than would be expected on the basis of economic performance alone: 2018 was one of those years. On the basis of the average relationship between economic growth and changes in donation levels, we would have expected donations to have increased slightly between 2017 and 2018. Instead, they fell considerably: 2018 was an unusually bad year, even taking the state of Australia’s economy into account.

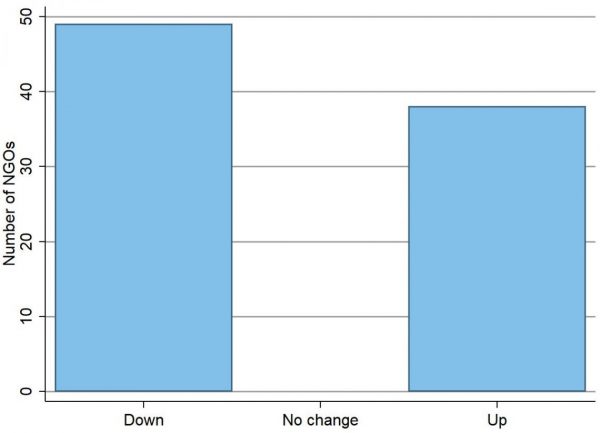

As I’ve pointed out previously, trends for the aid NGOs as a whole don’t necessarily reflect the experiences of all NGOs. The chart below shows Australian aid NGOs broken down into three groups: those whose revenue from donations increased, those that saw no change, and those NGOs whose donations fell. (All changes are after inflation is accounted for.) As you can see, not all NGOs saw their donation revenue fall. Nevertheless, donations fell for the majority of organisations.

Number of individual NGOs that donations rose or fell for

The next chart is a histogram which shows how much donations grew or fell. Minus one means a 100 per cent fall in income; two means a 200 per cent increase. A tiny group of small NGOs actually saw their income increase by more than 200 per cent, but I’ve excluded them from the chart for legibility’s sake.

The key takeaway from the chart is that while some NGOs’ revenue changed wildly, either for better or worse, the typical NGO only saw a small increase, or decrease.

Histogram of revenue change for NGOs

Such variation is intriguing. Yet try as I might, I couldn’t find relationships between other NGO traits and changing donation volumes between 2017 and 2018. Faith-based NGOs did no better, on average, than secular NGOs. NGOs with female CEOs performed neither better, nor worse, than those with men at the helm. The donation revenue of larger NGOs did fall more on average than smaller NGOs. However, averages for smaller NGOs were pulled up by some tiny NGOs with very large increases in donations (in proportion to their size). When these outliers were excluded, size also ceased to be associated with changing donation volumes. Even spending on fundraising did not seem to be associated with changing donation volumes. Although, before anyone races out and fires their fundraising team, I should emphasise it was hard to know how to best create this variable; I am not as confident of this finding as I am of the others.

The only trait I could find associated with change in donations in 2018 was change in the year before. If an in individual NGO’s donations fell in 2017, they were more likely to fall again in 2018.

2018 was a bad year for donations to Australian aid NGOs. In part this was because of sluggish economic conditions, but that’s not the whole explanation. Not all NGOs had a bad year, yet it’s hard to explain why some did and others didn’t. All that’s clear at this point, is that for many NGOs, the fall in donations in 2018 was part of an ongoing slide.

The aggregate data used in much of this post are collated by Devpolicy. However, disaggregated data used in some of the analysis come from ACFID. I am very grateful to ACFID and its member NGOs, for their transparency, data gathering, and interest in analysis. All analysis and opinions are mine alone.

About the author/s

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.