I-Kiribati workers en-route to employment in Australia (Credit: Holly Lawton)

The Pacific Labour Scheme: is it a flop?

By Stephen Howes and Holly Lawton

29 July 2019

The Australian Government’s Pacific Labour Scheme (PLS) provides workers from nine Pacific island countries and Timor-Leste opportunities for employment in low and semi-skilled occupations in rural and regional Australia for up to three years. It marked one year of operation on 30 June. According to some, there was little to celebrate. Reports called it a ‘flop’ and ‘broken’, that, after a ‘disappointing start’, was ‘letting relations down’. No-one was complimentary.

The common complaint was that the scheme’s first year numbers were unimpressive, with only 203 workers in its first year of operation. While now uncapped, the PLS had initially been established with an annual cap of 2,000, and, with that as a natural point of comparison, 203 certainly looks small.

Kiribati accounts for the bulk of the year’s workers with a 42% share of workers (Figure 1). Kiribati was granted a ‘head start’, as it was part of the PLS’s precursor, the Northern Australia Worker Pilot Program. In fact, about 50 of the 203 working in 2018-19 under the PLS arrived under the precursor scheme. The others all arrived this year. Vanuatu, one of the dominant three sending countries to Australia for seasonal workers, follows Kiribati with a 24% PLS share. Four other countries contributed a few workers each.

Figure 1: PLS workers by country

Yes, worker numbers are low. But it’s early days yet.

The Northern Australia Worker Pilot only involved some 80 workers from Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Nauru, all small and remote countries. MOUs with many of the region’s big labour mobility players were only signed relatively late last year. Tonga, Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea all joined in quarter 3 of 2018-19. Fiji joined in quarter 4.

The PLS is also a complex scheme, running across different sectors, all with their own needs and requirements in terms of labour market testing, skills and recruitment. Sending countries also need to gear up to support the PLS. Participation in the scheme doesn’t just happen. It is resource intensive – marketing to prospective industries and employers, supporting employer recruitment efforts, preparing workers to participate and to mobilise.

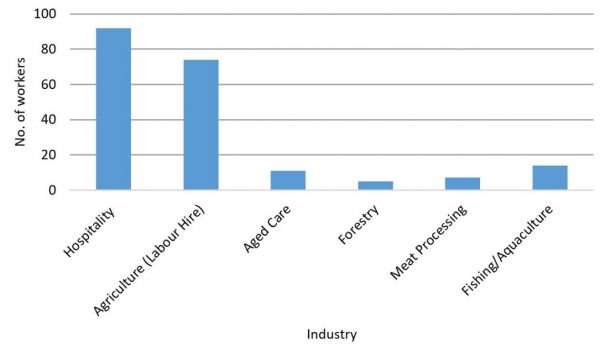

Six industries are currently participating in the PLS, with workers employed in Australia across a range of sectors from hospitality to aged care to meat processing (Figure 2). Perhaps the most positive indicator of future growth is that, while only a handful or so employers have already actually hired under the scheme, a total of 50 have gained the government-granted ‘approved employer’ status required to access it, with a further 14 employer applications under review.

Figure 2: PLS workers by industry

There is also room for geographical expansion. So far 85% of PLS workers have gone to Queensland, one of the pilot states (Figure 3).

Figure 3: PLS workers by state

The announcement of a new Horticultural Industry Facilitation Pilot Project facilitated by the opportunities the PLS provides suggests that Western Australia (and Timor-Leste) will soon be represented in the figures too. This state government pilot will work to facilitate linkages between Western Australia’s horticulture growers and workers in Timor-Leste.

39% of PLS workers are female, a big improvement on the longer-established and bigger Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP), where the ratio is 18%. Worker representation in industries included in the scheme has been heavily gendered. 100% of aged-care workers are female. 100% of workers in meat processing, forestry and fishing/aquaculture are men.

Other comparisons with the SWP are also instructive. It now receives upwards of 12,000 workers a year, but started slowly as well. In its first three pilot years (2008-09 onwards), the SWP had only 56, 67 and 423 workers. The SWP also had very little employer interest at first. In 2011, three years after the commencement of the SWP in pilot form there were only eight approved employers. Even in 2014, there were only some 40 approved employers under the SWP, compared to the 50 already signed up for the PLS.

Whether the PLS will approach the size of the SWP remains to be seen. Perhaps employers will try it, and move on. But it is definitely too early to write the PLS off. One year is simply not long enough a period to judge failure or success. And, in the first year, we should be counting employers not workers.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.

Holly Lawton

Holly Lawton worked as a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre, with a focus on Pacific labour mobility. She holds a Master of Development Practice from The University of Queensland.