The quiet revolution in Australian aid: a blog for Tim Costello and Aid Watch

By Stephen Howes

12 August 2011

I doubt that Tim Costello, Director of World Vision, and Aid Watch, the left-wing aid watchdog, agree very often. But they both, along with many others, think that too much government funding is given to private contractors to run Australian aid projects.

The Aid Watch website warns that “A major concern of Australia’s aid program is that it favours commercial interests in aid delivery.” Quoting 2006 figures, it notes that 45% of the aid program goes to private companies.

And then as recently as April this year, on ABC’s Lateline, Tim Costello said that “Australians would be surprised to know that some 40 plus per cent of the aid budget goes to private contractors, to Australian companies.”

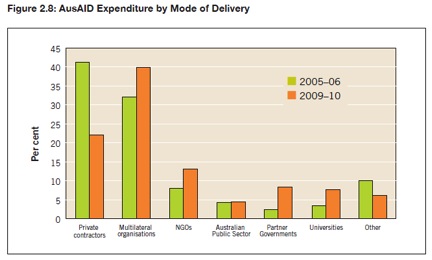

Well, they should be surprised, because it isn’t true. The Aid Watch figures are completely out of date. This graph from the recent Independent Aid Review shows how AusAID actually spends its money, and how that has changed. (Disclaimer: I was one of the five panel members commissioned to write the Review.) AusAID funds spent through private contractors were indeed 45% of the total in 2005-06, but fell to only 21% in 2009-10.

This dramatic change in the way Australia gives aid has gone largely unnoticed, though credit to Bernard Keane of Crikey for highlighting the Review’s findings in this area. AusAID rarely if ever reports its aid in terms of delivery mechanisms. Perhaps the first time the dramatic fall in the share of the aid budget channeled through the private sector was made public was in AusAID Director-General Peter Baxter’s opening address to the ANU Doubling Aid conference in February of this year.

What lies behind the numbers? The move away from ‘managing contractors’, as they are often called, has little to do with the arguments traditionally made against them. Any number of objections have been made over the years against contractors: the aid they deliver benefits only Australia (the ‘boomerang aid’ argument); aid shouldn’t be managed by for-profit companies; the particular companies which Australian aid funds are non-transparent; and they are too few in number to provide genuine competition in aid tenders.

However valid these arguments (or not), the reasons for the change in Australian aid lie elsewhere. The limitations of the contractor-led model of aid delivery were exposed in the first half of the last decade, when the Australian government put together a number of interventions, most prominently the RAMSI stabilization intervention for the Solomon Islands and the post-Tsunami package for Indonesia, whose size, urgency and complexity demanded a much more hands-on approach. More generally, there was a sense that development progress in PNG and the Pacific – always the acid test for AusAID – was tenuous at best, negative at worst, and that it was therefore time to try a different approach.

AusAID has since delivered no more than what it promised in the 2006 White Paper. This policy document stressed the need to work in partnership with recipient governments, other bilaterals, and multilaterals, and promised “greater direct, field-based, policy engagement with partner governments and hands-on management of the programs … rather than simply contracting out all services to private contractors.”

The biggest winner from this bipartisan reorientation of the aid program – started by the Coalition, continued by Labour – has been the multilaterals, such as the World Bank and the UN agencies, whose share of the aid program has increased from 32% to 40. In the past, the fact that – to simplify – multilaterals focus on Africa and we on Asia and the Pacific limited our funding to them. But a new strategy was developed to increase funding to multilaterals for activities in our region. And more Australian aid now passes through multilaterals than any other type of aid delivery channel.

Another winner has been the Australian public sector. AusAID staff numbers have certainly risen sharply, and more aid also goes through other government departments. The graph above only shows spending by other government departments of funds they receive from AusAID (5% of the AusAID spend), but they receive another 10% of the aid budget directly as well.

Perhaps most surprisingly, Australia now gives much more of its aid directly to the recipient or partner governments: the share of this type of aid has skyrocketed from 2% to 8. Australia had become very reluctant to actually hand over aid funds to partner governments after the bad experience with budget support to PNG in the 1970s and 1980s. But again, a rethinking has occured. Budget support to PNG was given with no strings attached. Funding to recipient governments now has lots of strings attached, and works well. The Indonesia schools program is the best example.

NGOs have also gained, with their share increasing from 8% to 13. This seems to be the only change which has been partisan in nature. Funding to Australian NGOs has increased sharply since Labour came to power, with core funding alone rising since then from $30 million to $98 million in the most recent budget.

And then finally universities have doubled their share of the aid budget from 3% to 7. As summarized here, governments from both sides have come to love scholarships in recent years.

These changes put together add up to a quiet revolution in Australian aid. Contractors haven’t gone out of business. The overall aid budget has roughly doubled in the last five years so funding to them has stayed roughly constant in nominal terms. But they are no longer the dominant force they used to be in the aid program.

I think that’s a good thing, and no doubt both Tim Costello and Aid Watch would agree. A more diversified approach to aid delivery makes sense. But it is not without its risks. Contractors are hardly ever given projects which they don’t have to compete for. Multilaterals never bid for projects. Nor do government departments. Universities and NGOs often don’t either. More generally, projects managed by contractors tend to come under greater scrutiny, both before and after the intervention, than those managed in other ways. Go to the AusAID website, and you’ll see far more evaluations of projects managed by contractors than of those managed by multilaterals or NGOs.

The point of this blog is not, however, to argue the case for or against what has happened, but simply to draw attention to the change. It’s time for the debate over the aid program to move on.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Crawford School of Economics and Government, ANU.

About the author/s

Stephen Howes

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University.