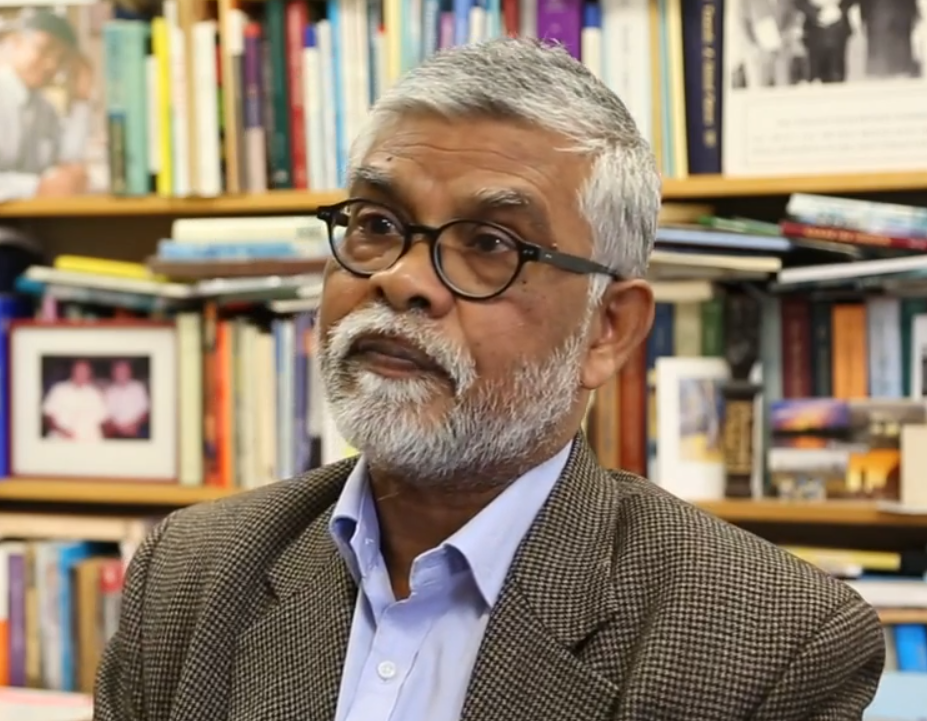

Tribute to Brij Lal

By Doug Munro

21 January 2022

The news of the death of Emeritus Professor Brij Vilash Lal on 25 December 2021 sent high voltage shockwaves among his friends and throughout his constituencies – the worldwide girmit studies community, the academic world of current Fiji politics, and imperial and diaspora studies generally. Within hours the tributes were pouring in as we lamented the loss of one of the greats. I don’t remember anything quite like it. The tributes are testimony to the high regard for Brij’s scholarship, which set the gold standard, and testimony also to his generous encouragement of others’ work and the affection with which he was held.

Compounding the sense of shock was the almost universal unawareness of the precarious state of Brij’s health. It was common knowledge that his eyesight was failing – a cruel blow to someone who treasured his books and loved reading – but few knew about the incurable fibrosis of the lung. He kept this almost completely to himself, not wishing to burden others with his problems, and he dealt with life’s capriciousness as best he could. His brave front was only too successful.

Born in 1952, the grandson of a girmitiya (indentured labourer), Brij grew up in straitened circumstances in Fiji on the family’s sugarcane holding in the backblocks of Tabia, Labasa. His parents were not only unlettered but illiterate. He was a quintessential scholarship boy from the provinces who did well at school, due in no small measure to the sheer good fortune of having inspiring teachers, about whom he later wrote with much affection. The other incredible piece of good fortune was coming to age when scholarships were available to bright young boys and girls to attend the newly founded University of the South Pacific (USP). He would have been left high and dry had he been born even a few years earlier.

Graduating in 1973 with high grades across the board, Brij then did his MA at the University of British Columbia, where he married Padma Narsey Lal, another USP graduate and his lifelong soulmate. He returned to Fiji to a junior lectureship at USP, but he hankered to do his PhD. He was awarded a postgraduate scholarship for doctoral studies at the Australian National University (ANU), but USP refused to give him leave of absence, so he threw caution to the wind and resigned. He returned to Fiji with PhD in hand, in late 1980 or early 1981, to take up the position that I was vacating.

Even had Brij confined himself to indenture and the social history aspects of post-indenture, it would still have been a sizeable and most respectable corpus of work. But during the 1980s the political history of contemporary Fiji became his forte and quickly overtook his concern with indenture, although he remained active in the latter field. The impetus was not the Fiji coups of 1987 – he started in 1983 with an article on the previous year’s election – but the coups did impart a sense of urgency and fuelled the moral dimension of his work, which was abhorrence of the country’s coup culture and adherence to liberal democratic principles, and the verdict of the ballot box being respected. But disappointment piled upon disappointment at transgressions from these ideals, providing him with endless copy for one journal article after another.

As well as being explicit in both his allegiances and his first principles, Brij had to be emotionally engaged with something to be intellectually engaged by it. He was at his happiest when patrolling the borders of scholarship and practical action, but he wasn’t comfortable being described as a public intellectual, preferring instead to being seen as what the French might call a spectateur engagé. The closest he got to being part of the political process was as one of the three constitution review commissioners who, in 1995–97, formulated recommendations for Fiji’s 1997 constitution.

There was a driven quality to Brij when it came to his writing. It was a case of ‘must do’ and ‘can do’. He once said to me, “I’d be enormously dissatisfied if I didn’t accomplish what I set out to do”. This explains why he was so taken by Mary Oliver’s poem When Death Comes (1991), which reads in part

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real…

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

There was no chance of that. Brij did all his writing in his office at the ANU Coombs Building. So far as I know he didn’t do any writing at home, except sometimes handwriting his next semi-fictional story when Padma wasn’t around. He worked at an astonishing pace and left others in his wake. I couldn’t keep up with him, and during our collaborations he sometimes got impatient when I fell off the pace.

But what caused him real anguish was being banned from Fiji, along with Padma, in 2009 on the spurious grounds that they were a threat to national security, and then the ban being confirmed in 2015, this time on the staggeringly false grounds that he had opposed the government’s moves towards democracy. To Brij’s abiding regret he remained an exile, holding out the (forlorn) hope that he would be allowed to visit the land of his birth and make a pilgrimage to Tabia, the place of his birth.

Thank you, Brij, for your writings as well as for our 42-year friendship and your support down the years, for our various collaborations, and now the memories.

Further reading

- An overview of Brij’s writings is best obtained by consulting his three volumes of collected essays. All are available as free downloads: Chalo Jahaji (2000), Intersections (2011), Levelling wind (2019).

- Brij’s 18 books and edited collections that were published or reprinted by the ANU Press are also available as free downloads.

- Brij’s Festschrift volume – Bearing witness: Essays in honour of Brij V. Lal, ed. Doug Munro and Jack Corbett (Canberra: ANU Press, 2017) – is likewise available as a free download. It contains a bibliography of his writings to 2017 (pp. 307–333).

- I have written a long book chapter on Brij’s life and career to 2008: ‘Brij V. Lal – journeys and transformations’, in Doug Munro, The ivory tower and beyond: Participant historians of the Pacific (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), pp. 243–309.

Editor’s note: Brij Lal was professor of Pacific and Asian History at the School of Culture, History and Language at ANU from 1990 until his retirement in 2015. This is the second of a series of tributes to him, collated at #Brij Lal.

About the author/s

Doug Munro

Doug Munro is an Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Queensland. He is co-editor (with Jack Corbett) of Bearing witness: Essays in honour of Brij V. Lal (ANU Press, 2017).