UN population projections: implications for international development

By Ian Anderson

27 August 2015

The UN has recently released revised projections for global population growth. Almost every page of their report, available here [pdf], has implications for international development. The following provides some of the key findings.

Global trends: more than half of global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa, including least developed countries

World population reached 7.3 billion in July 2015, 2 billion more than 1990, the baseline year for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). A further 83 million are projected to be added to the world’s population next year. Most of these will be born in low and middle income countries.

More than half of global population growth between now and 2050 is expected to occur in Africa, even if there is a substantial reduction of fertility levels in the near future. 19 of the 21 high fertility countries (average of five or more children per woman over her lifetime) are in Africa. Africa is projected to add 1.3 billion people to the global population between 2015 and 2050. Asia is projected to be the second largest regional contributor, adding 0.9 billion over the same period. The population in the existing 48 Least Developed Countries, many of which are in Africa, is projected to increase by 39 per cent by 2030 and to double from 954 million in 2015 to 1.9 billion by mid-century. Between 2015 and 2050, the populations of 28 African countries are projected to more than double.

Nine countries are expected to account for more than half of the world’s projected population increase over the period 2015–2050: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, USA, Indonesia, and Uganda (listed according to the size of their contribution to global population growth). Five of those countries are in Africa, three are in Asia (India, Pakistan and Indonesia). Only one country – the USA – is an OECD country.

Individual countries in Asia and the Pacific

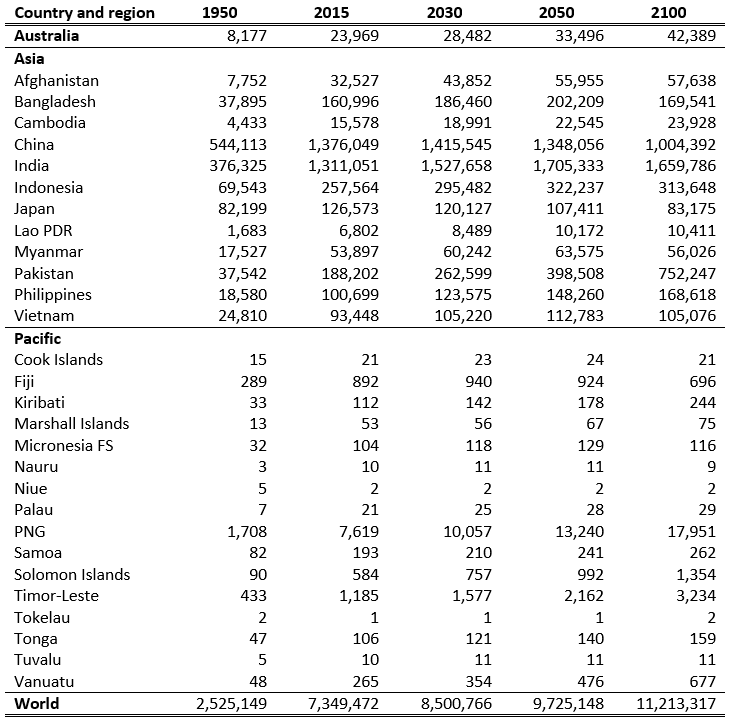

The table below captures the projections for population growth from the report in key countries of Asia and the Pacific.

Population projections (‘000 population)

For Asia, the report states that within seven years the population of India is expected to surpass that of China. By 2022 both countries are expected to have approximately 1.4 billion people. Thereafter, India’s population is projected to continue growing for several decades to 1.5 billion in 2030 and 1.7 billion in 2050, while the population of China is expected to remain fairly constant until the 2030s, after which it is expected to slightly decrease. The largest low-fertility (women having fewer than 2.1 children on average) countries in the world include China, Japan and Vietnam from Asia.

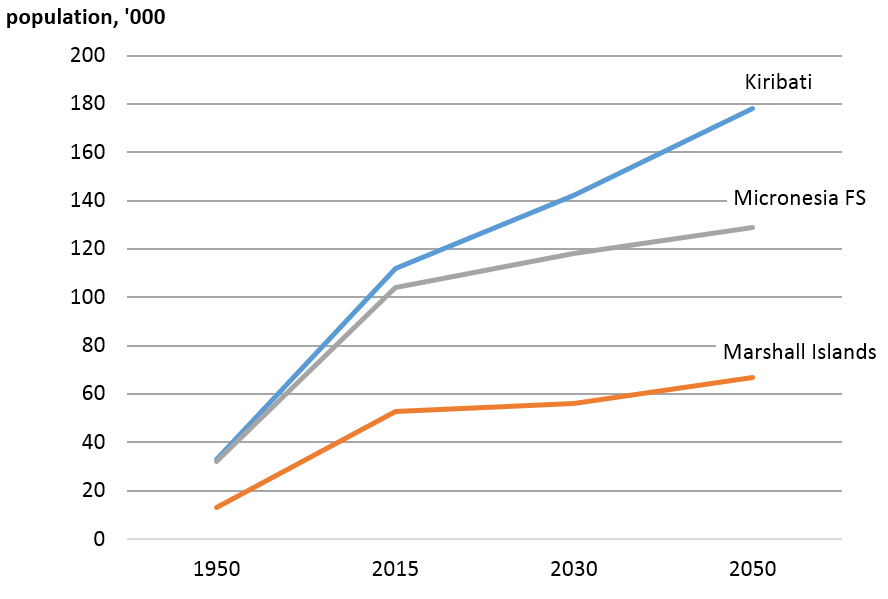

Unlike many similar reports, this report has projections for Pacific island countries, including many of the smaller and micro-states. One noticeable feature is the rapid population growth in certain Pacific island countries, especially in Melanesia. Vanuatu’s population is projected to increase by 33 per cent from 265,000 now to 354,000 by 2030; PNG’s population is projected to increase 31 per cent from 7.6 million to just over 10 million, and Solomon Islands’ population is projected to increase 29 per cent from 584,000 to 757,000. Also noticeable is the rapid increase in population historically of some smaller Pacific island countries, as shown in the graph below.

Population projections for small island states

Population ageing: especially in Asia

The report estimates that the number of people aged 60 or over will more than double by 2050 and more than triple by 2100, increasing from 901 million in 2015 to 2.1 billion in 2050 and 3.2 billion in 2100. 66 per cent of the increase between 2015 and 2050 will occur in Asia, 13 per cent in Africa. The number of persons aged 80 or over is projected to more than triple by 2050 and to increase more than seven-fold by 2100. Globally, the number of persons aged 80 or over is projected to increase from 125 million in 2015 to 434 million in 2050 and 944 million in 2100.

The report notes that ageing of the population has significant implications for the number of potential workers that can then provide tax revenues to support pensions, etc. By 2050, there will be almost complete global parity between the number of older persons aged 60 and above, and the number of children under the age of 15. Currently, African countries have on average 12.9 people aged 20 to 64 for every person aged 65 or above (the ‘Potential Support Ratio’, or PSR), while Asian countries have PSRs of 8.0. Japan, at 2.1, has the lowest PSR. The report notes that:

By 2050, seven Asian countries, 24 European countries, and four countries of Latin America and the Caribbean are expected to have PSRs below 2, underscoring the fiscal and political pressures that the health care systems as well as the old-age and social protection systems of many countries are likely to face in the not-too-distant future.

The overall conclusion is clear. Even though these are estimates and projections, population growth will continue to have major implications for international development. There are opportunities and risks. Those countries that invest in the human capital of their growing populations, pursue good economic policies, and have the enabling environment to create meaningful and productive jobs are likely to benefit from a demographic dividend. Those countries that fail to invest in human capital or pursue inappropriate economic policies are likely to face the challenge of large numbers of unemployed and, subsequently, large cohorts of the aged poor. Changes in the size and structure of populations for the coming decades have largely been set. But countries can still choose good policies or bad.

Ian Anderson is a Research Associate at the Development Policy Centre. He has over 20 years international development experience with AusAID, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

About the author/s

Ian Anderson

Ian Anderson is an associate at the Development Policy Centre. He has a PhD from the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; over 25 years of experience at AusAID; and since 2011 has been an independent economics consultant.