Under the partnership between the Crawford School of Public Policy and the School of Business and Public Policy at the University of Papua New Guinea, a number of ANU Crawford School lecturers teach UPNG undergraduates and graduates in economics and public policy. Due to COVID-19, a significant part of the teaching last semester was online.

In May 2021, towards the end of the semester, we surveyed some students on their experiences of online learning. Given the COVID-19 vaccine rollout that started around the same time, we also took the opportunity to ask them about their attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination. A total of 281 students, mainly undergraduates, responded to the survey: 56% men and 44% women. Around 220 respondents were in their first year of studies, and the rest were undergraduates from later years.

A recent online survey from PNG’s The National newspaper found that 77% of respondents did not want to be vaccinated. This suggests that PNG has a high level of vaccine hesitancy. In Australia, at the end of last year (before vaccines had been approved for use), 73% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they would get the vaccine if it became available and was recommended for them. A number of large-scale surveys across Africa found that at least 59% of respondents would accept a vaccine if it became available. For example, in one survey, at the end of 2020, an average of 62% of respondents across six countries said they would “definitely” or “probably” take the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as possible. Younger people (aged 15–25) were only slightly less positive: with an average of 59% in the two positive categories.

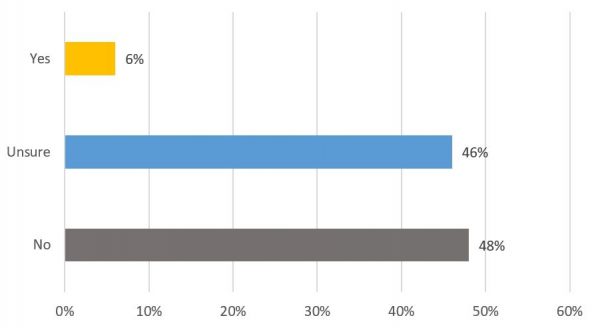

In contrast to The National’s survey, our survey gave respondents the option to choose “unsure” in their opinion on vaccine. It also asked specifically about the AstraZeneca vaccine. This addition resulted in a still high, but far smaller, number who said they would not want to be vaccinated – 48% compared to 77%. A much smaller number of respondents (6% vs 23%) said that they wanted to take the vaccine. 46% stated that they were unsure whether or not they would take the vaccine.

Responses to the question “would you like to be vaccinated with the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine?”

The survey also asked respondents to provide a brief free-form reason for their response. Some were brief, and others were highly detailed. The most common reason for wanting to take the vaccine was the improved safety that vaccination provided. The biggest reason for being unsure about vaccination was a lack of requisite information to make a proper judgement. Examples of the free-form responses from respondents unsure about taking the vaccine include:

[In] regards to this question, the Government of Papua New Guinea have not made more awareness on this COVID- 19 vaccine so most of us are confused about it.

And:

There should be some proper awareness of the vaccine so that we will knowingly vaccinate ourselves.

Negative rumours and debate on social media were the most common reasons given by those who do not want to take the vaccine. Misinformation was also evident in a few responses. The link between those who knew someone who had been vaccinated and being more likely to want to be vaccinated was not statistically significant.

Access is also a key issue. Even if everyone in PNG wanted to be vaccinated, at this stage there are not enough vaccinations available. One respondent noted that they were unsure of taking the vaccine as a young person:

I feel like there are people who are more desperate or need it more than my relatively introverted, hygienic, self-isolating self: front line workers, elderly, etc.

Our data shows that many minds are not made up on the issue of vaccination. Many respondents noted the need for further awareness and information on COVID-19 and vaccinations. These responses suggest that authorities need to do more to ensure that accurate and trustworthy information reaches these students and, in all likelihood, the public at large in PNG. In the next blog, I look into which sources of information respondents trust most.

Author notes

Sincere thanks to the respondents who took part in this survey.

The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses a number of COVID-19 vaccines, including the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine available in PNG, as safe and effective at protecting people from the serious risks of COVID-19. According to Oxford University, as of June 2021, 2.6 billion people have been vaccinated against COVID-19. The risk of vaccination is classified by the WHO as very low.

The following are some reliable sources of information on COVID-19 and vaccine research, data and risks:

- COVID-19 vaccine safety (World Health Organization information page)

- The Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine: what you need to know (World Health Organization information page)

- How many people have been vaccinated for COVID-19 globally (data from Oxford University)

- Resources for journalists covering COVID-19 and vaccines (Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy)

- Global trends in COVID-19 (data from Johns Hopkins University)

This is the first blog in a the #vaccine hesitancy and trust series. You can read the second blog here.

Correction 25 June 2021: In May 2021, towards the end of the semester, we surveyed some students on their experiences of online learning.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership. The views represent those of the author only.

Interesting that you were able to survey students over 1 year in advance of the vaccine being released in PNG and still think that the result could be in some way relevant for release now, without any update……

Or did you do your survey in May 2021?

I may not be a learned person, but I employ over 50 people and I spent several hours discussing the vaccine roll-out with them. You have barely scratched the surface in reporting the remarks of students. I found the biggest hesitancies were:

1) Is the vaccine safe? We don’t know this medicine, its new. The virus doesn’t look so bad, I think I will wait and see “with my own eyes” if it’s safe for people I know to take it.

2) The govt always lies to us, why would we trust them on this?

3) We heard that the vaccine is banned in Australia for under 60s – why are they telling us it is safe here in PNG? How can it be dangerous for them but safe for us?

4) I think I had the virus already, can I get infected again, do I need the vaccine?

5) We are hearing about side effects, are these normal in vaccinations? We didn’t hear about these types of side effects in polio and other vaccines, or other medicines.

6) It’s been 16 months and I don’t personally know anybody that died of the virus, how dangerous can it be?

7) After 16 months only 170 people died, how many died from other things.

8) My son/daughter/mother/father and other people I know died from ______ while all this was going on. Why is the govt not spending money and making restrictions/laws for those things if so many people are dying. Why only for Covid?

Far down the list of questions was the racist or religious disinformation.

But I found that the biggest cause of vaccine hesitancy was that they are skeptical of the govt and media’s constant harping on about a virus that has a very small death count in comparison to other causes and disproportionate govt response to it. The term “Don’t believe your lying eyes, it’s how we tell you it is, not how you see it” is the best way to describe the confusion.

By the end of our session, I had answered everybody’s questions and given them a clear understanding of the virus, the vaccine, how they work, their importance in stopping the spread of disease, and countered all the superstitions and urban myths. Everything I presented was fact based and researched through the CDC, WHO, Govt, and media.

Grand total result, was that not one of my staff had been convinced to drop their guard and sign up for the vaccine. Though most of them did thank me for clarifying all their questions, because right now they are being fed half truths by people they are told to respect that can’t answer their questions or are just making up obvious lies to cover their lack of knowledge (insert: pastors, big men, politicians, doomsayers and academics, etc) or obfuscating the truths and information to push their own narrative, but not actually answering the questions that people are asking.

Noted that the govt did put in the newspaper several pages trying to answer a lot of these questions to dispel the above concerns, but it was the wrong median and it came from the wrong people. Prof. Glen Mola is not well respected outside of his own medical/govt circle and his talk of “Racist ” was the stupidest thing that could ever have been published if the intent was to break down the myths and convince people to accept the vaccine. This approach only put a new thought in their minds, that perhaps the “white” govt paid doctor was trying to convince them to take a dangerous vaccine, “why else would he say that, when we were not thinking that?”

For disclosure, I am not anti-vaccine at all. I have had all my shots, the last being (Polio, Hep, and a few other boosters only 3 years ago). I forwarded an offer to my staff to organize a company wide vaccination appointment time (during paid work hours) to any staff that would like to partake. When I had zero names on the list I was intrigued and set about holding a staff meeting to dispel any myths and give a very concise and clear explanation of the virus and vaccines. I believe that my staff are adult enough to make up their own minds about their (and their families) health directives, and that my role is only to present them with honest and factual information, the choice is then up to them to make.

Thanks Jobs, and yes that was an unfortunate typo, apologies for the error, there will be a note added to correct this shortly. The survey was conducted in May 2021.

I agree I just scratch the surface on reasons for the levels of vaccine trust. It would take a whole blog just to describe the diversity of legitimate concerns about the vaccine and legitimate distrust in authority and the media presentation of COVID19, and I do plan to discuss these in future blogs.

Thanks Rohan, this is useful. Can you confirm data is from May 2020? Will you repeat these questions in another end of semester survey? Interested to know if attitudes have changed a bit now?

Hello Emma, my apologies for the error, yes, the survey was conducted in May 2021.