“We can’t borrow money from overseas, just to send back overseas again”: a powerful but logically flawed argument that would devastate the Australian aid program

By Anthony Swan

11 December 2014

If it is said enough does it make it true?

The Labor Party and the Greens might want us to continue to borrow money to give it away, but we think we have a responsibility to our children and grandchildren to repair the budget, to build a stronger, more prosperous economy, to create opportunity for everyone to get ahead, but we are not going to continue to spend money [on foreign aid] that we have not got.

Mathias Cormann, July 2014

We can’t borrow money from overseas, just to send back overseas again.

Julie Bishop, June 2014

[The government would not] borrow money to give it to people overseas.

Tony Abbott, May 2014

The bottom line is that we can’t borrow money then give it away, we can’t do that and we’re not doing that with the Australian people, and we can’t do that with people internationally.

Joe Hockey, May 2014

It is stupid to go ahead and commit money that we’re just going to borrow from overseas to give back to people overseas. We’ve got to get into a sustainable economic position, we’ve got to live within our means.

Andrew Robb, September 2013

…it simply reflects the reality that you can’t borrow money to spend on aid.

Bob Carr, May 2013

The Australian government is now in the ludicrous position of borrowing money overseas to send it back overseas as foreign aid.

Nick Minchin, March 2013

I happen to think it doesn’t make a lot of sense for us to borrow money from the Chinese to go give to another country for humanitarian aid.

Mitt Romney, October 2011

We’ve got to be cautious when we’re borrowing money from overseas to send back to overseas … because we’ve got to pay the money back.

Barnaby Joyce, February 2010

Clearly not but are we to believe these statements? What is the logic and what are the implications of these statements for Australian aid if actually implemented?

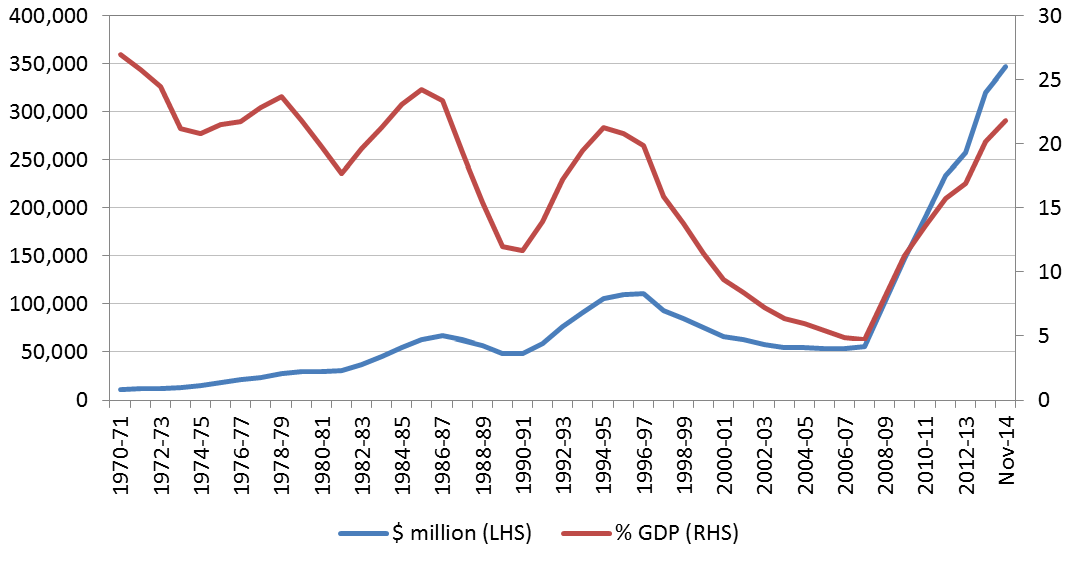

While the statements were made over a period of nearly five years, they speak to the underlying philosophy of our current government and are highly relevant to the future of the aid budget given the desire of the Coalition to repair the budget and reduce government debt (see Figure 1). Failure to pass budget savings measures (reportedly $28 billion), a worse than expected deterioration in terms of trade, and new spending measures such as counter-terrorism and the war in Iraq, have added to the challenge of deficit reduction.

Figure 1: Australian Commonwealth Government debt

This worsening situation is on top of the May budget, which was light on spending cuts anyway (see Figure 4 here). What success the Coalition has had with its budget cuts has firmly centred on the aid budget: $7.6 billion over five years compared to the Government’s estimate of what Labor would have spent or 10 percent in real terms by 2015-16 relative to 2012-13. Indeed, in the run up to the release of the government’s MYEFO, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has flagged the risk of further cuts to the aid program.

This worsening situation is on top of the May budget, which was light on spending cuts anyway (see Figure 4 here). What success the Coalition has had with its budget cuts has firmly centred on the aid budget: $7.6 billion over five years compared to the Government’s estimate of what Labor would have spent or 10 percent in real terms by 2015-16 relative to 2012-13. Indeed, in the run up to the release of the government’s MYEFO, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has flagged the risk of further cuts to the aid program.

Are such cuts justified by the quotes listed above?

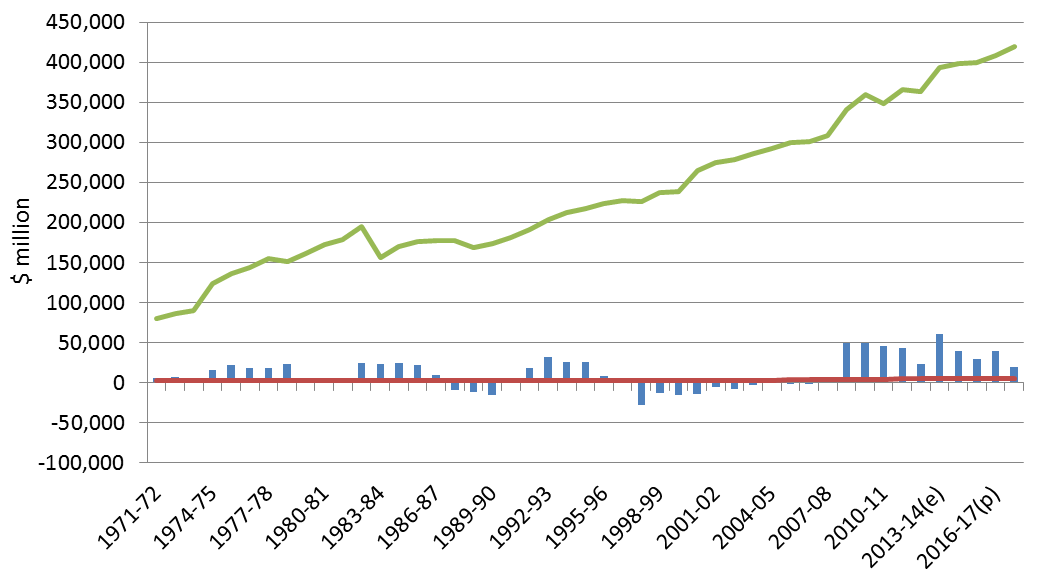

If the statements were simply a comment on the contribution of aid spending to government debt (whether the debt is sourced from overseas or not really doesn’t matter) then they would have some merit but only under the assumption that government revenue is fixed. The government has to borrow whenever it runs a budget deficit (when spending is greater than revenue) so any additional government spending, whether on aid or elsewhere, contributes to government debt if total revenue is not sufficient. However, aid spending represents just 1.2 per cent of total government spending and hence its relative contribution to government debt is very small. Figure 2 shows that in recent years the aid budget is small relative to additional government borrowing and tiny compared to non-aid government spending. Cutting the entire aid budget would do little to solve the government’s debt and deficit problem.

Figure 2: Australian aid spending and non-aid spending against changes in government debt, 2012-13 constant million dollars

Moreover, the level of government revenue is not really fixed. Broadening of the tax base, ensuring an appropriate return on Australian non-renewable resources, and short term measures such as a deficit tax are all options for reducing government debt and deficit. Government borrowing is not necessarily linked to aid spending once both sides of the budget – revenue and expenditure – are considered.

Moreover, the level of government revenue is not really fixed. Broadening of the tax base, ensuring an appropriate return on Australian non-renewable resources, and short term measures such as a deficit tax are all options for reducing government debt and deficit. Government borrowing is not necessarily linked to aid spending once both sides of the budget – revenue and expenditure – are considered.

There is also an implicit suggestion in many of the above statements that the aid budget is entirely funded by government borrowing, particularly borrowing from overseas. This is not the case. Over the last seven years of government budget deficits, government borrowing from overseas (as measured by foreign currency denominated debt) has not funded any government expenditure, including aid spending, and Australian dollar denominated government borrowing has on average funded only slightly more than 10 per cent of total expenditure (see note at end of blog). Furthermore, it does not make sense to draw a correspondence between the allocation of funds across government programs (such as the Australian aid program) and how specific funds were raised by government (such as through government borrowing).

This is because once the total funding envelope for spending has been determined, the opportunity cost of raising funds is the same across types of government spending. So while the cost of raising funds will differ depending on how they were raised – such as through income tax, GST or issuing government debt – the opportunity cost of all dollars raised for funding is identical and is equal to the (marginal) cost of raising the last dollar of funding.

The implication is that aid spending is no more related to government borrowing than any other spending program and it does not cost more to raise funds for aid spending than other forms of government expenditure. It follows that borrowing or interest costs associated with government debt should not be imposed on the aid budget or any other particular spending program (which is consistent with good public financial management practice).

Despite the above statements not making much sense, what would happen if they were actually implemented? Over 47 years (from 1971-72 to projections in 2017-18), the Australian government has increased or will increase its debt levels in 35 of these years, a proportion of nearly 75 per cent. Alternatively, Australian government net debt has increased or will increase in 60 per cent of years over the same period. Either way, any rule which essentially eliminated funding of Australian aid in years in which the government increased its level of debt would devastate the aid program, both in terms of the amount of funding and aid effectiveness, given the variability of funding and inherent uncertainty associated with government budgets. So while Julie Bishop has extolled the virtues of an aid program that provides “stability and future certainty” to stakeholders, this type of rule would actually create instability and future uncertainty to the point that the Australian aid program may not be able function at all.

Note: The Australian federal government borrows money by issuing Treasury bonds (known as Commonwealth Government Securities – CGS). CGS denominated in foreign currency can clearly be identified as government borrowing from overseas but essentially no additional government debt has been raised in this way for more than a decade. Recent increases in government debt have been through issuing CGS denominated in Australian dollars but this is not exactly borrowing from overseas even though some of the buyers may reside overseas.

Anthony Swan is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

About the author/s