What Australian aid flows show

By Terence Wood

13 January 2021

Development Policy Centre staff and associates have used many methods to study Australian government aid. Richard Moore used qualitative interviews to gauge the impact of AusAID’s integration. Luke Levett Minihan and I undertook website content analysis to assess aid transparency. Matthew Dornan, Sabit Otor and I used project data to examine aid effectiveness. Ashlee Betteridge studied the aid program’s use of communications tools. Our Stakeholder Surveys have tracked changes in aid program performance. And Stephen Howes has systematically investigated problematic parts of the aid program, such as the Innovation Exchange (aka the iXc).

Today we are launching a new report in which, Matt Dornan, Sachini Muller and I have analysed publicly available data on aid flows. (The report has been a long time in the making: Matt and Sachini no longer work at Devpolicy, but are co-authors of the paper, reflecting their earlier work and insights.)

In this blog post I will cover the four key points from the report.

While most donors have become more generous, Australia has become less

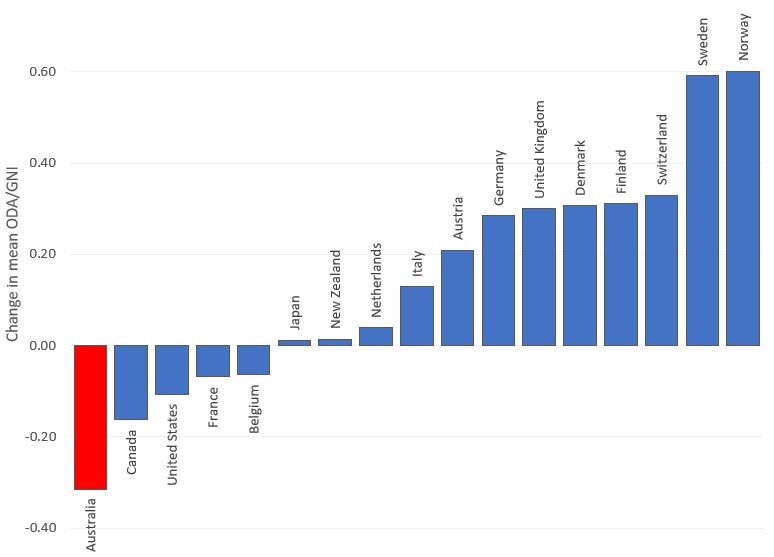

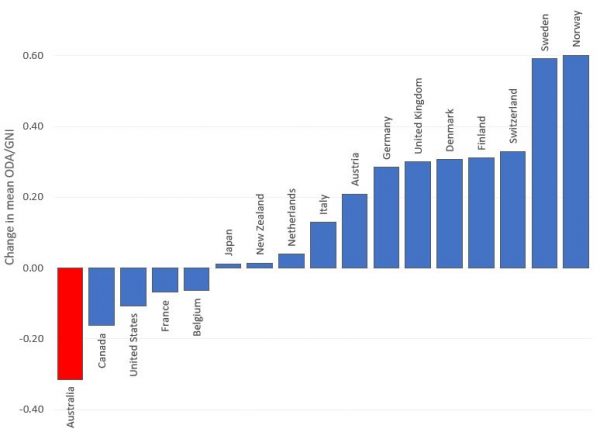

Usually, as countries become more affluent they become more generous aid donors. Specifically, as their GDP per capita goes up, countries usually give an increasing share of their GNI as Official Development Assistance (ODA). As a result, most of the countries that were members of the OECD DAC (the OECD’s donor club) in the 1970s are more generous donors now than they were in the early 1970s.

There are exceptions though. Australia is one. In fact, it’s the donor whose ODA/GNI ratio fell the most since the early 1970s. (In the figure below we’ve averaged ODA/GNI across five-year periods and compared the first (1970-74) to the most recent with data (2015-19). As we discuss in the report, there are other ways of making the comparison. Australia came out worst in almost all of them.)

Change in Aid/GNI from 1970-74 to 2015-19

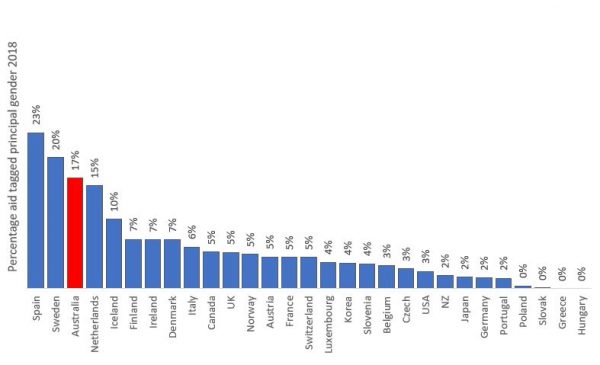

Australia focuses well on gender and women’s empowerment

When donors report to the OECD they state which of their projects are ‘principally’ or ‘significantly’ focused on gender and women’s empowerment. This is self-assessment, and is not perfect, particularly in the case of the ‘significantly focused’ measure. But the ‘principally focused’ measure is good enough to use in comparisons. And when we compared Australia with other donors, Australia performed very well.

Share of donor ODA principally focused on gender

Usually in the report we used multi-year averages to prevent findings from being driven by idiosyncratic years, but owing to (legitimate) changes in Australia’s reporting practices in 2018 we did not do this for gender. The same changes make comparisons over time difficult, but Australia’s gender focus has clearly improved since 2004, presumably because of the emphasis Julie Bishop placed on the issue.

Australia is not doing enough to help Pacific countries with climate change adaptation

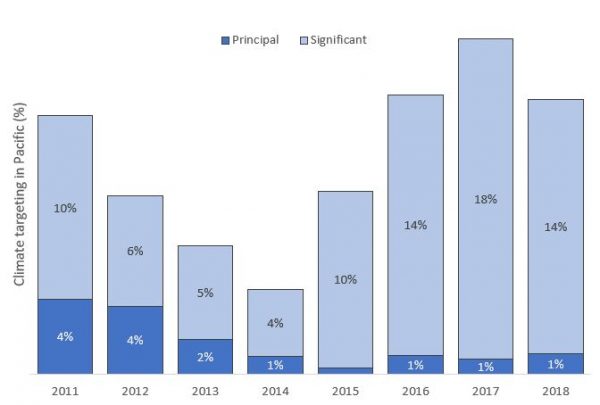

Wealthy countries and major greenhouse gas emitters need to do one thing above all to help developing countries: reduce emissions. But, unfortunately, even if we do this, some climate change is already on its way. And this climate change is likely to pose major challenges to developing countries in the Pacific. Donors need to focus some of their aid to the region on helping countries adapt to climate change. The extent to which Australian aid is primarily and significantly focused on climate change adaptation in the Pacific is shown in the next figure, which is, once again, based on Australia’s reporting to the OECD.

Australian aid focused on climate change adaptation in the Pacific

At first glance the figure looks encouraging. The share of Australian aid targeted as significant for climate change adaptation is going up. Yet, as with gender, the significant marker is problematic. The aid program is committed to mainstreaming climate change adaptation into its work. This is commendable, and no doubt is the source of some of the rise in the significant indicator. But when I examined Australia’s 2018 Pacific projects tagged as having a significant focus on climate change adaptation, the three largest were all to do with governance and included one on macroeconomic policy in Papua New Guinea. Maybe climate change adaptation was considered as the work was designed. But this type of work should not be confused with aid focused on directly helping countries adapt to climate change. Such work is best captured by the principal marker. As you can see, it has fallen since 2011 and is currently at about 1%. Australia needs to do more to help Pacific countries adapt to climate change.

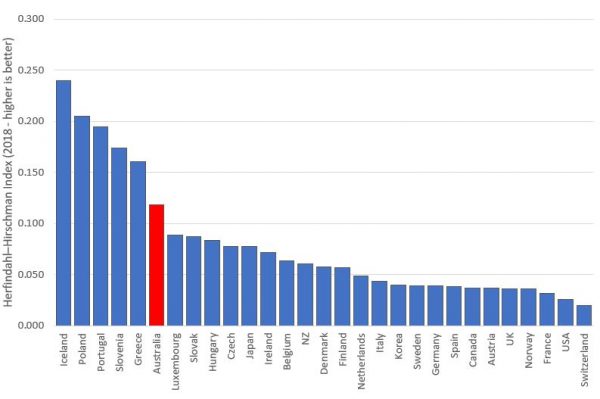

Australia doesn’t fragment aid too much across recipients

Generally, donors should avoid fragmenting aid across too many countries. Less fragmentation ought to mean lower overheads and greater expertise about the countries donors focus on. Australia, as we show in the report, gives some aid to almost every eligible recipient country on earth, but mostly it gives small amounts. The bulk of Australia’s aid is focused on a few large recipients (Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Solomon Islands). As a result, when we compared Australia to other donors using a standard measure of fragmentation (the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index) we found Australia performed well.

There’s a lot more in the report: we look at sectors and where Australia gives its aid; we also look at aid volatility and project fragmentation. We’ve placed most of our data online too in a ZIP file.

Data on aid flows won’t reveal everything important about aid. Other approaches are needed. But analysing aid flows provides vital clues in the puzzle of understanding donor performance.

You can read the full report here and the executive summary here.

Disclosure

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

About the author/s

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.