Who opposed Australia’s aid cuts?

By Terence Wood

24 November 2015

Following the Australian government’s cuts to aid earlier this year, a number of public opinion polls showed broad support for these cuts, including polls reported as showing even Greens voters were in favour of cutting aid. We weren’t convinced. And we wanted to see what would happen when people were asked about these cuts in possession of accurate information, while also confronted with policy trade-offs. We also wanted to analyse the disaggregated data in the same way I was able to do with the ANU Poll data I blogged about recently–we wanted to learn the traits associated with support or opposition to the cuts.

So we commissioned our own question in an Essential Media omnibus poll.

The question we asked was:

Every year about 1.2% of Australian federal government spending is spent on foreign aid to poor countries. Recently the government announced that it plans to cut foreign aid by nearly 20% starting in July. They have justified this as a means of preventing government debt rising. Which of the following options would you prefer (each involves equivalent amounts of money)?

- That aid not be cut and government debt levels increase by a small additional amount next year (approximately 0.4%) as a result of this.

- That aid not be cut and taxes be raised by a small amount (approximately 0.3%) to produce the same reduction in government debt sought from the aid cut.

- That aid not be cut and other government expenditure be cut by a small amount (approximately 0.2%) to produce the same reduction in government debt sought from the aid cut.

- That aid be cut by 20% as the government is currently planning.

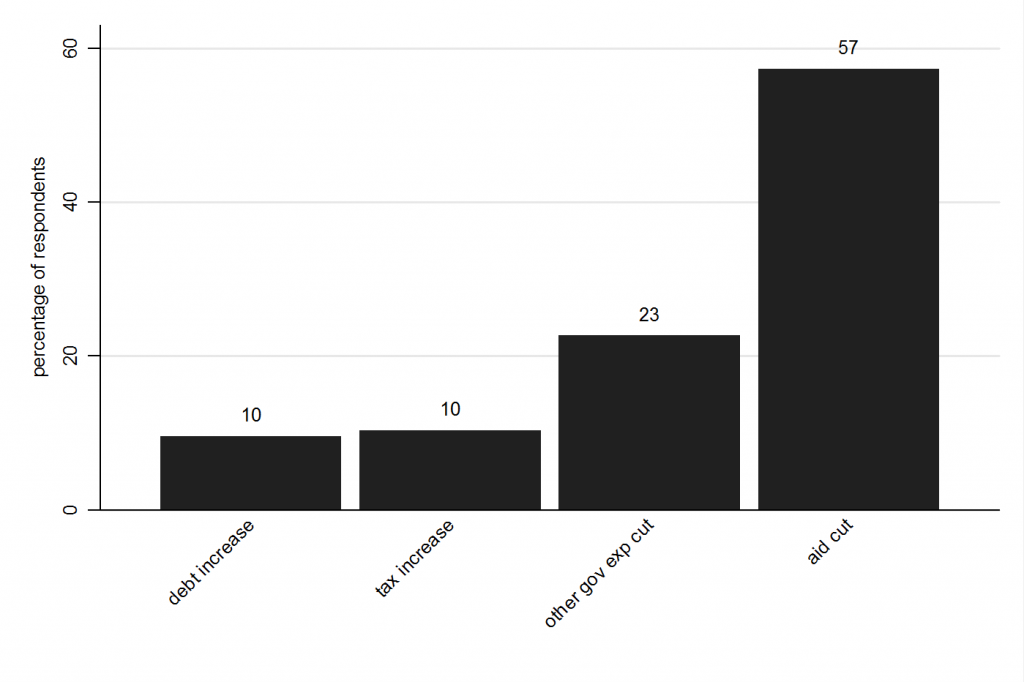

As the chart below shows, the majority of respondents (57% versus 43%; and therefore, by inference, the majority of voting age Australians) supported the cuts.

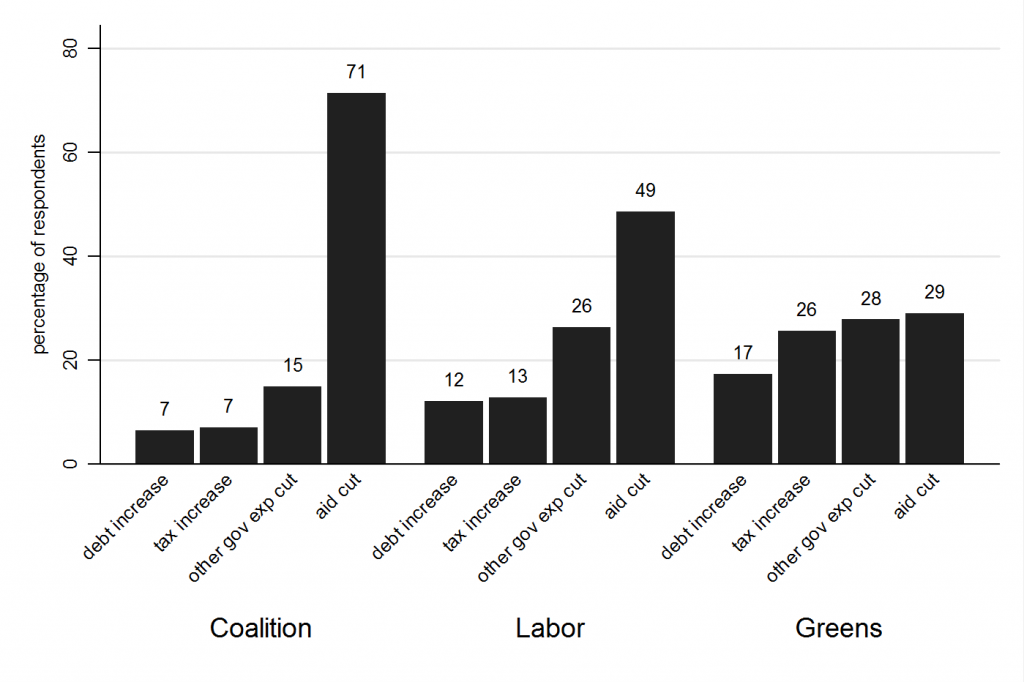

Support, however, wasn’t universal. The chart below shows support broken down by party. Coalition supporters clearly favoured the cut over alternatives, but 51% of Labor supporters preferred one of the available policy alternatives and 71% of Green supporters preferred an alternative.

Support, however, wasn’t universal. The chart below shows support broken down by party. Coalition supporters clearly favoured the cut over alternatives, but 51% of Labor supporters preferred one of the available policy alternatives and 71% of Green supporters preferred an alternative.

This chart offers a sense of how support for the cut falls across party lines, but because we were given disaggregated data by Essential Media and because these data came with other information about the survey respondents (albeit not nearly as much data as I received from the ANU Poll–there was no information on religion or foreign policy opinions, for example) I was able to use multiple regressions to identify traits associated with opposition to the aid cuts. (To get a sense of the meaning of multiple regression results and how the process untangles the effect of the variable of interest from other variables, read my first post in this series; for in depth results and more detail on methods, see this discussion paper.) To make the analysis less technically complex I grouped support for policy alternatives into one category: ‘opposition to cuts’.

This chart offers a sense of how support for the cut falls across party lines, but because we were given disaggregated data by Essential Media and because these data came with other information about the survey respondents (albeit not nearly as much data as I received from the ANU Poll–there was no information on religion or foreign policy opinions, for example) I was able to use multiple regressions to identify traits associated with opposition to the aid cuts. (To get a sense of the meaning of multiple regression results and how the process untangles the effect of the variable of interest from other variables, read my first post in this series; for in depth results and more detail on methods, see this discussion paper.) To make the analysis less technically complex I grouped support for policy alternatives into one category: ‘opposition to cuts’.

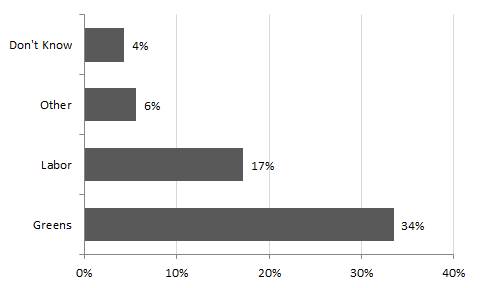

Unsurprisingly, given the magnitude of the difference among supporters of different parties shown in the chart above, even when I controlled for other variables, there was still a strong relationship between party support and opposition to the 2015 aid cuts. The chart below shows that, with other variables controlled for, Labor supporters were 17 percentage points more likely to oppose the cuts than the Coalition supporters, while Greens supporters were 34% more likely.

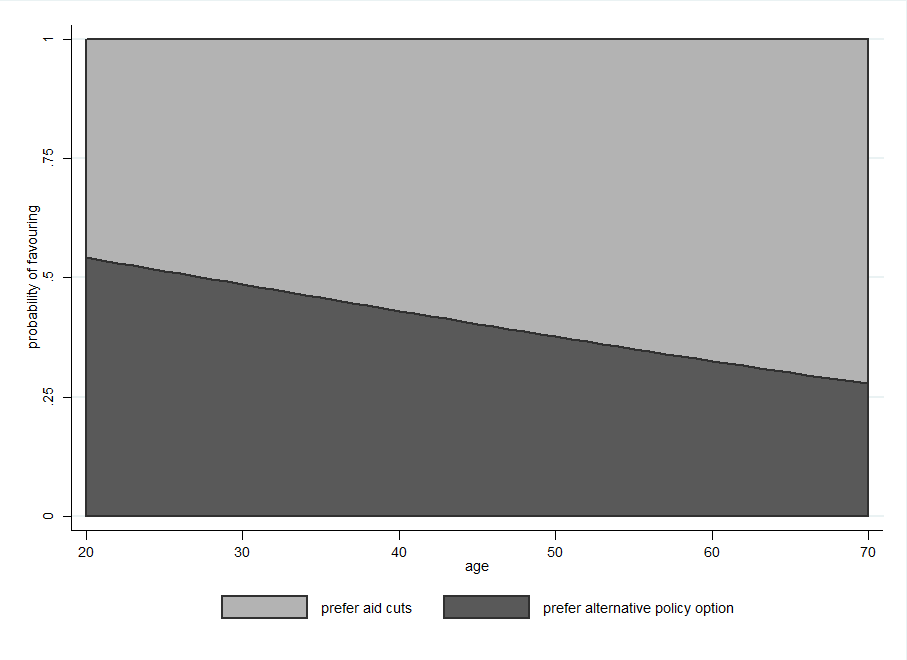

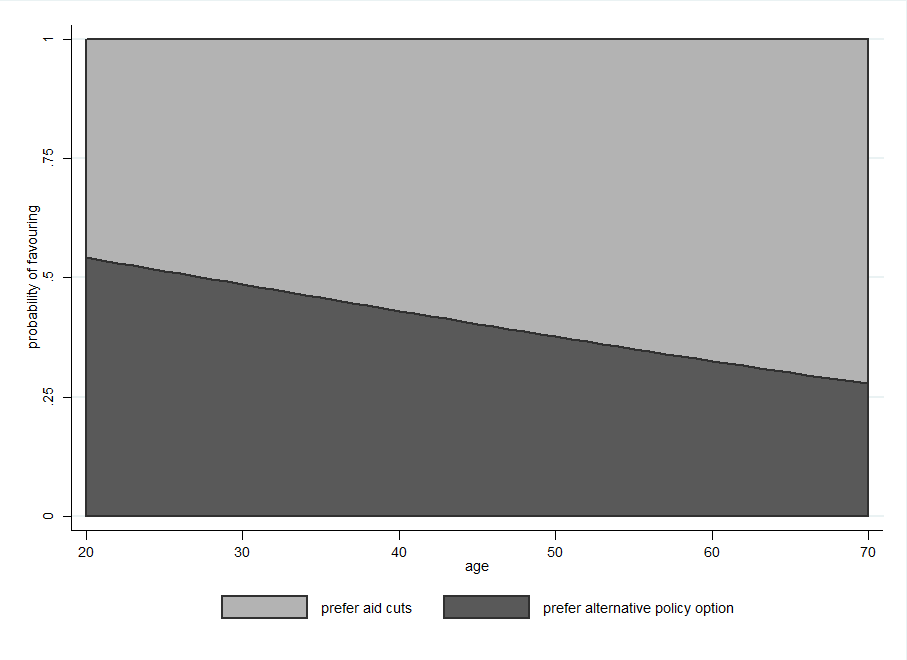

As with the ANU Poll data, once other variables were controlled for there was no relationship between income and views on the aid cuts, but there was a clear positive relationship between having an academic education and opposition to the cuts. Also, similar to the ANU Poll there was a clear negative relationship between age and opposition to the cuts.

As with the ANU Poll data, once other variables were controlled for there was no relationship between income and views on the aid cuts, but there was a clear positive relationship between having an academic education and opposition to the cuts. Also, similar to the ANU Poll there was a clear negative relationship between age and opposition to the cuts.

While these findings were similar to those I found in the ANU Poll, in contrast to my analysis of the ANU Poll data I found no relationship between gender and views about the cuts.

While these findings were similar to those I found in the ANU Poll, in contrast to my analysis of the ANU Poll data I found no relationship between gender and views about the cuts.

What does all this mean? First, the findings suggest we shouldn’t be quite as pessimistic about public support for the 2015 aid cuts as some surveys would have us believe. And yet, it’s still true that there is an uphill battle to be had on aid volumes. While the ANU Poll findings showed that most Australians are supportive of giving aid, the Essential Media polling still showed a majority of Australians were OK with the 2015 aid cuts.

For people who opposed the cuts and want to see more aid, both polls point to a base for campaigning work–a group of people most likely to be amenable to mobilisation.

Both of the polls suggest this base is primarily amongst younger, better educated Australians, and among people who are politically left-leaning. (While the ANU Poll found a relationship between gender and support for aid, our poll on the cuts didn’t, and given the current campaign fight is about the volume of aid it would be wisest to follow the Essential Media findings.)

Unfortunately, the Essential Media survey didn’t provide data on religion or other foreign policy views but, because most of the findings from the Essential Media analysis were similar to those from the ANU Poll, it seems safe to assume that opposition to aid cuts will also be strongest amongst the non-religious and religious people who attend worship often, and that Australians with an internationalist bent (people more favourable to Indonesia and China, and multilateral organisations) will also be allies.

Finally, the negative relationship in the ANU Poll data between concern with the government’s finance and support for aid emphasises the importance of combating the mistaken belief that aid is anything more than a trivial component of the federal government’s budget woes.

There is still a lot to learn about building an effective campaign against Australian aid cuts, much which can only be learnt from the practical work that campaigners are already undertaking, but public opinion data does provide a good sense of where support for aid, and opposition to cuts, is strongest. We’re conducting ongoing research in this area, and we’ll keep you updated with what we learn.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His PhD focused on Solomon Islands electoral politics. He used to work for the New Zealand Government Aid Programme. The full discussion paper on which this post is based can be found here, and the first post in this analysis here.

About the author/s

Terence Wood

Terence Wood is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. His research focuses on political governance in Western Melanesia, and Australian and New Zealand aid.