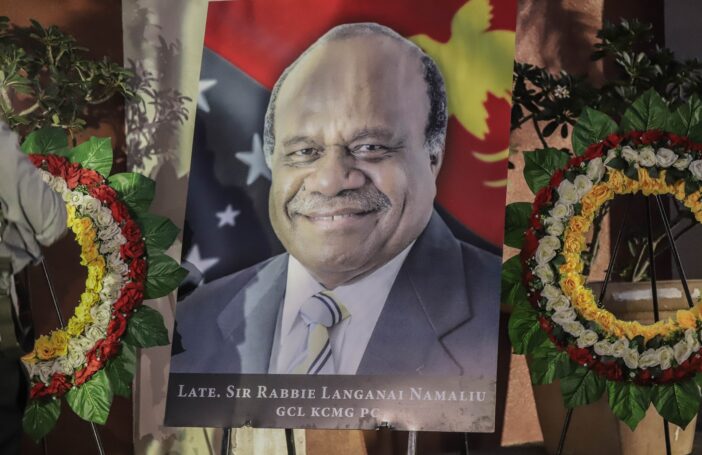

This is part one of an edited extract from a speech by former Papua New Guinean Prime Minister Sir Rabbie Namaliu delivered at a 1995 conference in Australia, and published in the Pacific Economic Bulletin in the same year. Sir Rabbie died on 31 March 2023: read his eulogy.

Papua New Guinea today faces its greatest challenges since independence. How these challenges are addressed will determine our future stability, growth and unity.

Even though these are great challenges, there has been one other period in our short history which has in fact been more critical, at least potentially so. The rebellion on Bougainville, and the closure of the Bougainville Copper Mine, occurred in the early period of my term as Prime Minister. Our recent and current economic and fiscal problems have tended to dull the enormity of the crisis my government confronted in late 1988 and 1989.

The closure of the mine, and the rebellion, had a tragic effect on the whole national economy. At the time of its closure, the Bougainville Copper Mine provided about 10 per cent of Papua New Guinea’s GDP, 36 per cent of export earnings, and 24 per cent of total government revenue. Virtually overnight, a massive slice of the whole economy – a third of exports, and a quarter of revenue – was taken away. The situation was made even worse by the destruction of the North Solomons cocoa and copra export industries, and by the massive cost of the security force operations on Bougainville.

In total, these conditions were far more serious, and far more unexpected, than recent events have been. Despite that, the record of Papua New Guinea’s economy in the period immediately following the Bougainville Copper Mine closure is one to be proud of, and one which those in authority today can learn from.

In 1990 we managed to keep the budget deficit to 100 million kina, or 3.3 per cent of GDP, and to a similar figure in 1991. Bearing in mind that, in 1990 we lost, and lost virtually overnight, a quarter of total state revenue, that is no minor achievement.

Even though we lost more than a third of export earnings with the mine closure, we managed to maintain foreign reserves at a comfortable level. There was no foreign reserves crisis, as there was last year.

In the same period, and this is where the real lesson lies for today and for the future, we were able to achieve real mining and petroleum growth by 23 per cent in 1990, and a massive 41 per cent in 1991 – our best ever performance.

The closure of the Bougainville Copper Mine, and the rebellion, ought to have had horrendous consequences for the mining sector and for mining investor confidence, especially international confidence, yet 1991 was our best year ever for mining and petroleum growth.

Between 1988 and 1992, the Porgera Gold Mine, the Misima Gold Mine and Hides Gas were brought to production, and the nation’s first ever oil-producing project, Kutubu, was brought to production just months after the change of government in 1992.

These facts confirm a remarkable resilience in the Papua New Guinea economy during that period, strong investor confidence, and an ability to negotiate and bring online more resource projects than were put together in the previous 30 years.

This record, and the fact that we were able to maintain foreign reserves, a strong currency, and social cohesion, offers real hope for the future, even though today we face quite different difficulties and challenges.

I have briefly gone over the record of my government, because some commentators have sought to distort it, and have failed to give us credit for managing a period which could have ruined our economy, given the enormity of the Bougainville Copper Mine closure and the rebellion as a whole. That brings me to current conditions – and to the challenges that lie ahead.

Despite the enormity of Papua New Guinea’s problems – and there is no point in downplaying their extent – I have confidence in our political and economic future. If that confidence is not misplaced, our social future and unity will be secured as well.

Our strengths outweigh our weaknesses. The commitment to true, competitive and open democracy among our people is as strong as it ever was. That is a tremendous strength and advantage. We have a judiciary that is fiercely independent, and we have a free and open press, and freedom of debate and discussions, as well as freedom of dissent. The basis of our democracy is strong, even if some of its component parts are not. We are rich in resources, and how we manage the development of our resources will be crucial to our economic and social future.

Our location gives us enormous potential advantages in trade and investment. We have to make the most of them, remembering that we are a part of the region and the world and cannot isolate ourselves from reality.

We have a tragically underutilised population. We must train and assist our people to play a more productive, useful role in nation building and community building.

We have strong, mutually beneficial relationships with countries such as Australia – relationships we must never take for granted, and work constantly to diversify and strengthen.

Above all else, we must not squander the benefits of resource development – and we must not presume that the world owes us a living and that investors have nowhere else to go.

These are just some of our strengths, but they represent an imposing list, by any measure.

This is the first blog in a two-part series. Read the original article in the Pacific Economic Bulletin.